The morning after the first night of Ronald Harwood’s Taking Sides in May 1995, I received a call from Otto Klemperer’s daughter.

‘Tell me,’ said Lotte, ‘is it true that, in Mr Harwood’s play, the denazification attorney addressed Dr Furtwängler as “Wilhelm”, or even “Willi”?’

I said something in reply about dramatic licence and the interrogator being, erm, an American.

‘No one,’ thundered Lotte Klemperer down the phone, ‘ever called my father “Otto”.’

Appearances meant everything to the generation of great conductors that survived the Nazi era, whether as anxious refugees or, in the case of the Berlin Philharmonic chief, as a cultural poster boy for a criminal regime. After the defeat of Hitler, Furtwängler argued that he had given selfless service to his fellow Germans, keeping alive the Geist of Bach and Beethoven. ‘People never needed more, never yearned more to hear Beethoven and his message of freedom and human love than precisely these Germans, who had to live under Himmler’s terror,’ he told the tribunal. ‘I do not regret having stayed with them.’

Furtwängler was not a member of the Nazi party and there is evidence that he helped a number of Jewish musicians to escape the Gestapo, and the country. His lofty self-exculpation was rubber-stamped by the western allies who did not want this central figure to go conducting for the Russians in East Berlin. It has since been swallowed by a slew of biographers all the way down to Harwood who, having raised a quizzical eyebrow in his script, let old Willi off with no more than a finger-wag.

Now, out of the blue, a letter has turned up that shows Furtwängler in a less noble light. The letter is written by the eminent pianist Artur Schnabel to his secret American lover (which may be why it took so long to turn up). Schnabel, who was forced to leave Germany, recounts a summer’s evening he spent with Furtwängler in Italy shortly after he was cleared to resume conducting in 1947.

‘Last night Furtwängler and wife came to see me,’ Schnabel reports to Mary Virginia Foreman. ‘It was partly pleasant, partly opposite. So far it seems to me that these Germans cannot be helped, nor can they help themselves. He demonstrated the same old blending of arrogance, cowardice, and self-pity.’ Schnabel, the first to record the 32 Beethoven sonatas, was one of few living musicians whom Furtwängler acknowledged as an intellectual equal and whose opinion he valued.

Schnabel continues: ‘After the first “world war” the German leaders circulated as facts what obviously had been fake. For instance: that they had lost the war only because the home front had stabbed the army in the back. The Germans had no guilt whatsoever… Now Furtwängler went as far last night (he got terribly excite [sic], hysterical, shouted and roared), as to say that he has never known any Nazi. And that Germans and Nazis are not only absolutely different beings but hostile to each other.’

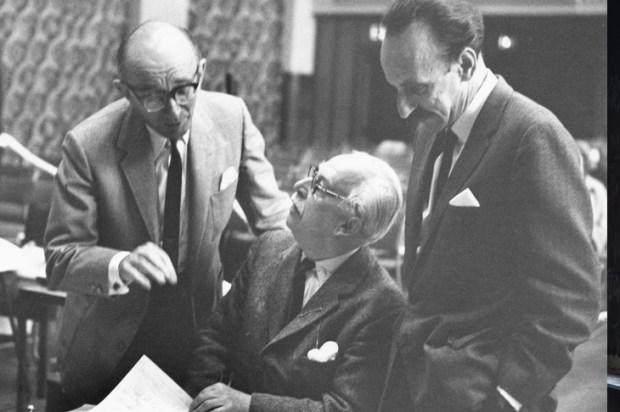

Imagine that. Furtwängler had been made vice-president of the Reichsmusikkammer in 1933 by Joseph Goebbels and had conducted often in Hitler’s presence. I have a photograph of him extending a hand to be shaken as Hitler approaches him after a concert, and another of him standing with the Führer at Bayreuth. ‘Never known any Nazi’? Take it from the top, Willi.

Schnabel hears his guest complain that ‘millions of Germans are now murdered daily, and that the whole world shows its decadence by its total lack of charity’. Furtwängler goes on to admit ‘without having been asked, that he has had quite a good time during the “regime”.’

This letter, from an impeccable source with no axe to grind, is a massive iconoclasm. It shatters the long-held image of Wilhelm Furtwängler as a man who did his best for music in terrible times, and replaces it with a man in denial of his central role in the Nazi cultural myth, a willing executioner of music for the greater glory of the regime.

He had a good time in the Reich, he admits. Any pity he feels is not for Hitler’s victims but, first, for himself, and second for Germans now living under Allied occupation. Furtwängler, seen through Schnabel’s eyes, is a shoddy hypocrite who, like Germans as a whole, is unwilling to admit a scintilla of guilt for his complicity with Hitler. He is not a saviour of great art. He’s just a very slippery character.

The fall of the Furtwängler myth is no small crash. A conductor of spiritual mien who conjured an aura of religious solemnity in his concerts, he is a role model for the Abbado-Barenboim generation and a persona of undying fascination. More than anyone, he established the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra as the acme of interpretative legitimacy. Topple Furtwängler, and the German tradition loses its authority. The emperor concerto may need new clothes.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in