You can, perhaps, glimpse Lorenzo Lotto himself in the National Gallery’s marvellous exhibition, Lorenzo Lotto: Portraits. At the base of an altarpiece from 1541 a gaggle of paupers stretch their arms up in hopes of receiving the charity being handed out by Dominican friars above. One of these, a bearded, red-robed man, is supposed to be a self-portrait.

If that is the case, it was a characteristic place to put himself. Lotto (1480/1–1556/7) was an intensely pious man and, in later life, poverty-stricken. But the most unusual point about this picture is that for the rest of the crowd of indigents he made studies from life of genuine poor people (and noted the modelling fee he paid them in his book of accounts). Few other Italian Renaissance artists would have striven so hard for verisimilitude.

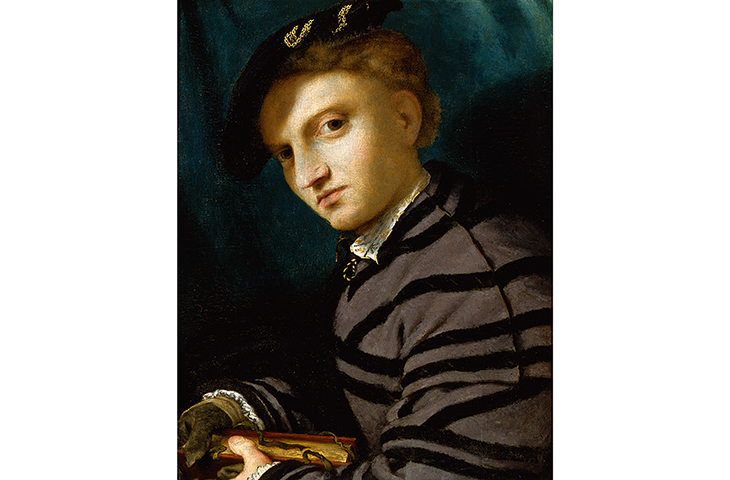

Like Caravaggio more than half a century later, Lotto seems to have been an artist who preferred to work as much as possible from life. The results he got could be startlingly close to photography. His portrait of ‘Bishop Bernardo de’ Rossi’ (1505) (see p31) is an amazingly exact account of the fall of light across this man’s soft features, delicately picking up each fold of skin, the moles along the line of his chin and the indentation at the point of his nose.

Lotto, though erratic, was at his best a truly great painter of human individuals. But he also painted portraits not just of people but of things. The untidy desk in the double portrait of ‘Giovanni Agostino della Torre and his son, Niccolo’ is a careful depiction of real bureaucratic clutter, down to the white inkstand spattered with drops of black.

Time and again Lotto focuses sharply on a single item such as this humble office utensil or one of the Anatolian rugs he painted so memorably that they’ve been given the name ‘Lotto’ carpets. One of these, and several other oddments including a 16th-century dress, are included here for purposes of comparison.

However, he was not simply a realist. In his work there was a strange crossover between the human and the holy, with the result that several religious paintings pop up unexpectedly in this exhibition. In the first room there is a beautiful early altarpiece from 1506 showing ‘The Virgin in Glory with Saints Anthony Abbot and Louis of Toulouse’. But the Mary in this altarpiece is not the standard representation, but stolid and middle-aged with a faintly disapproving air.

Scholars argue that this is a portrait of Caterina Cornaro, a Venetian woman who became Queen of Cyprus by marriage and lived at Asolo, the little town in the Veneto for which the altarpiece was painted. At the time, this notion would have verged on the blasphemous, but it rings true. In fact, the saints, especially the elderly Anthony Abbot with his jutting, pointed beard, look like portraits, too.

The picture is fantastically naturalistic but simultaneously bizarre and awkward. The Madonna hovers inertly in midair a few feet above the ground, too heavy to rise further. It’s easy to see why Lotto was overshadowed by his younger rival Titian, in whose great ‘Assumption’ of a decade later the Virgin sweeps heavenward with superb brio. That kind of grand composition was beyond Lotto, whose work didn’t please sophisticated Venetian tastes.

Not only do his saints look like portraits, on occasion his portrait sitters pretended to be saints too. ‘Friar Angelo Ferretti’ (1549) is vividly characterised: intense and a little haggard. But a butcher’s cleaver is embedded in his cranium and a large dagger protrudes from his chest. This was because Ferretti wanted to identify, as we say these days, as St Peter Martyr, a Dominican inquisitor assassinated in 1252.

Lotto’s clients often acted out a private allegory or drama, though not necessarily a sacred one. In one of the finest, the anonymous sitter fixes us with a sad look, his right hand resting on a table top. Beneath his fingers are rose petals, and nestling among them is a beautifully painted miniature skull.

It is not hard to decode. This expensively dressed fellow with a fine beard clearly wanted to be shown brooding on love and death, and was possibly in mourning. In other cases, Lotto’s symbols are more puzzling. Why, for example, is a green lizard rearing up beside more rose leaves on the desk of another melancholy young man painted between 1530 and 1532? Art historians are still wondering about that.

In 1895 Bernard Berenson claimed Lotto as the most modern of all Renaissance artists: ‘His spirit is more like our own.’ More than a century later, that still feels true — not just in the naturalism with which he depicted his subjects, their anxieties and melancholies, but also in the weird ways they want to present themselves.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in