In the early 1370s an elderly Scandinavian woman living in Rome had a vision of the Nativity. Her name was Birgitta Birgersdotter, and she was later venerated as St Bridget of Sweden. In her account of the experience, transcribed by her confessor, she described herself as an eye witness. Her narrative began: ‘When I was present by the manger of the Lord in Bethlehem…’

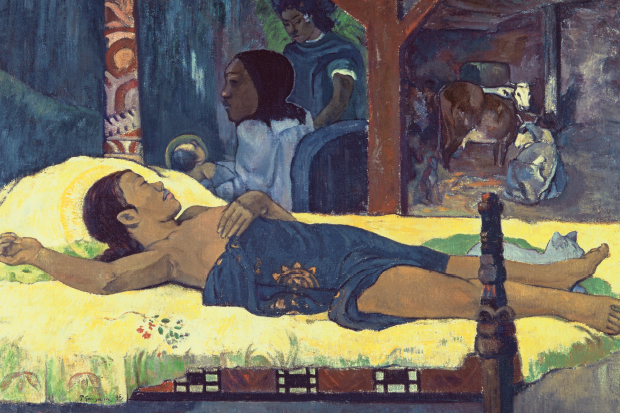

Around a century later, Piero della Francesca (c.1412–92) used Bridget’s vision — or parts of it — as a starting point for a painting. This picture, now in the National Gallery, is one of the best-loved depictions of this immensely popular subject in the history of art.

In some respects, Piero followed Bridget’s visionary account closely. She related how the moment of childbirth itself was ‘so sudden and instantaneous’ — and miraculously free of pain and mess — that she could not discern how it had taken place. At one moment, the Virgin was standing, ecstatic and lost in contemplation. The next the child was lying on the ground, ‘naked and shining’. Then Bridget heard ‘angels of miraculous sweetness and beauty’ singing.

The Virgin instantly clasped her hands and worshipped the baby, who, feeling the coldness and hardness of the ground, raised his little arms imploring her to lift and hold him. Piero, like many 15th-century artists, depicted this moment: the Adoration of the Virgin in which the Madonna kneels before the baby. He borrowed other features from Bridget’s narrative — the Virgin’s ‘beautiful golden hair’, for example, and the angelic choir. But he translated the latter from visionary sound to sight.

Piero’s heavenly band, singing and strumming on their lutes, are as prominent as the Virgin and her child. The colours of their robes — white, mulberry and light blue — form a chord, each note distinct yet harmonious. The open mouths of the singers in the row behind give a clue to the pitch and volume of their voices. This is a picture you can almost hear.

In other ways, however, Piero went off Bridget’s script. His soundtrack contains, in addition to the angelic quintet, the braying of a donkey behind them in a rustic barn. He also added a second, slightly later episode, the Adoration of the Shepherds, who stand behind Joseph. St Bridget watched the Nativity take place in a cave — a location adopted by many artists, including Giorgione, Mantegna and Leonardo. In contrast, Piero has represented his own familiar landscape.

His biographer, James R. Banker, suggests that on the right Piero has put in a view of Sansepolcro, his native town, ‘probably looking down via delle Guinte’ — the street on which the Della Francesca family lived — from the east. On the left there is a landscape in which a silvery river flows through high rocky hills. Sansepolcro is sited in the upper Tiber valley, very close to its confluence with another stream, the Afra, winding down from the mountains above. The simple barn, too, is a typical Tuscan structure. Thus the sacred drama of Christ’s birth unfolds in Piero’s own neighbourhood.

This was a private picture, not an altarpiece or a commission from a patron. That’s one thing we know for sure. In 1500, eight years after the artist’s death, it was noted in an inventory: ‘a panel painting with the Nativity of our Lord in the hand of master Piero.’ It was then in the room previously occupied by Madonna Laudomia, the widow of Piero’s nephew Francesco.

This has led several scholars to suggest that it might have been a gift from Piero to the newly wedded couple. The match — an alliance with a wealthy family from Montevarchi, a little town 29 miles away — was an important event for the Della Francescas. In 1481 Piero himself led a family deputation there to make the arrangements.

The ‘Nativity’ was highly suitable for a nuptial bedroom, procreation being — in the eyes of the church and also to middle-class clans such as Piero’s — the point of marriage. But the wedding-gift theory is not the only one; Piero might simply have done it for himself, to adorn the family dwelling. Perhaps he painted the ‘Nativity’ — one of his last pictures, if not the final one — to keep his eyes and fingers active.

Around the same time, Piero wrote that his mind was now ‘out of use and consumed by age’ (he was then probably approaching 70). This was in the preface to a brilliant treatise on geometry, The Little Book on the Five Regular Bodies, undertaken, he claimed, to prevent his faculties becoming ‘torpid’. The ‘Nativity’ might have served a similar function. Possibly he left it unfinished. The areas of thin and bare surface paint were partly caused by a disastrous 19th-century ‘restoration’, but perhaps some areas were never executed in the first place.

By this point, Piero had become more a scholar-gentleman than an active artist. The ‘Nativity’, however, betrays no diminution of skill or intensity. On the contrary, it reveals him moving into a novel phase: blending the lucid geometry of his earlier work with the naturalism of Flemish artists (like several of Piero’s later works, the ‘Nativity’ is in the favourite Flemish medium of oil).

Through a quirk of history, Piero was a major influence on mid-20th-century British painting. The late Gillian Ayres told me what a hero he was to contemporaries at art school in the 1940s. He was also an inspiration to the young David Hockney. The latter’s ‘Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)’ (1972), recently auctioned for an amazing price, has some of the same ingredients as Piero’s ‘Nativity’: a figure placed horizontally at the bottom — a swimmer rather than the infant Saviour — another gazing downwards, and a hilly landscape behind. Are these echoes, perhaps subliminal, between two ostensibly very different paintings nearly 500 years apart? Pictures, too, have progeny, which sometimes pop out in the most unexpected times and places.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in