Gerald Murnane is the kind of writer literary critics adore. His novels have little in the way of plot or even character, and it is hard to tell the narrator from the writer, so that all his stories might be essays; his sentences are weirdly flat but interrupted occasionally by wild visions. Try this, for example:

There in a room with enormous windows a man with a polka-dotted bow tie broadcasts radio programmes to listeners all over the plains of northern Victoria, telling them about America where people are still celebrating the end of the war.

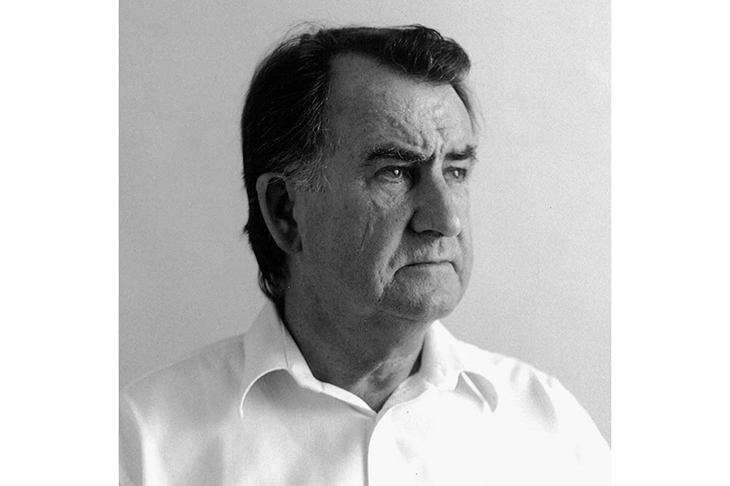

Where are we? Who can see the bow tie on the radio announcer, and did the war end recently or long ago? At the risk of a little racial profiling, this all sounds so odd that it has to be Australia, and Murnane himself is a perfect Australian type. The profiles and publicity materials accompanying his books describe a kind of outback Eliza Doolittle, a man who has spent the past 40 years writing to limited acclaim, but now those novels have been rediscovered and are being republished in America and the UK. It’s a romantic story, about unlikely literary success, and Murnane plays his part perfectly. He lives in the remote village of Goroke, in the north-west of Victoria, while the New York Times calls for him to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Murnane’s subjects are obsession, frustration and, like Virginia Woolf or James Joyce, the feeling of a mind alive in thinking and sensation. He also really likes marbles. In his first novel, Tamarisk Row — published in Australia in 1974 but only now in the UK — a boy called Clement Killeaton scrapes a circular track into the dust in the alley behind his house. Clement lives in Bassett, ‘the largest city for a hundred miles in any direction’, which is both a huge overstatement and tells us all we need to know about the quality of daydreams in a town like Bassett. Clement pushes marbles around this track and imagines great colourful horse races. He has inherited this daydream from his father, a failed gambler, and for father and son the races are a substitute for religious belief: something bigger, more exciting than this world.

The novel is divided into short sections, each with a title and each only one long paragraph. These are not quite chapters, but more like episodes. ‘Old Blue Nancy’, for example, halfway through the novel, is about a local woman who may be an urban myth, a kind of grotesque child-snatcher who both worships at and defecates in the local church. As is perhaps obvious by now, this is all a deeply unsentimental portrayal of childhood. Clement and his friends are grasping, cruel and watchful; next to marbles, Clement’s chief obsession is trying to convince the local girls to show him their underwear.

Where Tamarisk Row is about childhood, Murnane’s most recent novel centres upon an old man. The narrator of Border Districts is a study in repression, a monkish figure who has renounced his family and books and life in a city and moved to what he describes as ‘this township just short of the border’. This might be a place, or a metaphor for death. He resolves to write a report, upon his own life, but this seems to consist mainly of reading articles about religious history and thinking about stained glass. Like Clement, he loves marbles, which spark his reveries, and Border Districts reads less like a novel than a meditation. The narrator recalls imagining, as a child, that all the books he read were ‘passage after passage or chapter after chapter in one never-ending book’, and this captures something of the shifting, mesmerising experience of reading this novel.

What all this adds up to is a puzzle for the reviewer of Murnane’s works. Many compare him to James Joyce, and there is something very Joycean here: the scatological Catholicism, the children with dirty fingernails. But nobody reads Joyce for pleasure, and the risk of selling Murnane as a high modernist artist of great literature is that this misses something eerie and enthralling about the experience of reading him. Tamarisk Row is a remarkably acute portrayal of what it is to be a bullied, confused boy, while Border Districts is dazzling for its austerity, its cruel purity. Their sentences ring in the ear, and the novels stay with you.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in