A kind billionaire called Jeremy Hosking, whom I do not know personally, has invited us to join the Britannia Express, a steam train, on 30 March, the day after Brexit. The train will traverse Wales and England, starting at Swansea and ending in Sunderland. In an unspoken rebuke to the metropolis, it will not travel via London. The train will, says the invitation, commemorate ‘the UK’s exit (or non-exit) from the European Union’. This is the opposite, I suppose, of the European train which people like the late Sir Geoffrey Howe constantly exhorted us to climb aboard. What to do? The most likely situation on the day is that we still will not know our country’s fate. I’d love to watch Brexit get up steam, but what if, thanks to Theresa May (with a bit of help from Chris Grayling), we pass our time in a siding near Crewe?

The news that former Paras who took part in Bloody Sunday in 1972 may be charged with murder, contrasts interestingly with the fate of the INLA terrorists who blew up and killed Airey Neave, Mrs Thatcher’s right-hand man, in the car-park of the House of Commons in 1979. In his forthcoming biography of Neave (The Man Who Was Saturday), Patrick Bishop draws attention to the fact that Harry Flynn, a man suspected by the police of involvement, is alive and well and was last heard of running a bar in Majorca. He is not being pursued. Throughout the 40 years since the assassination, Neave’s family has never been made privy to any information known to the authorities, on the grounds that this might prejudice any reopening of the case. It has not, however, been reopened. All efforts by Bishop to study Home Office and Met Police records have been blocked. Why the zeal in the first case, the foot-dragging in the second?

The departure of Jonathan Dimbleby from Any Questions? is sad for me. I first listened to the programme when the chairman was Freddie Grisewood, and first appeared on it under the over-emollient David Jacobs. Then I served under the likeable but somehow underpowered John Timpson. Since 1987, I have appeared under Jonathan. He is the master of all subjects, and much more genial than his interrogative manner suggests. I have never known him seem bored on air, although, over more than 30 years, he must often have been. Jonathan’s Achilles heel, I discovered quite early on, is the BBC. If you criticise it on air, he gets slightly trembly, casts aside his otherwise impeccable impartiality and tries to put you down. This in turn provokes me, so I make sure to attack the corporation every time I go on the programme. It is sad that the organisation to which he has shown such loyalty is now shedding the values for which the Dimbleby dynasty stands. These include a high standard of knowledge, a carefully achieved balance between courtesy and challenge, and complete clarity of diction. None of these values is compatible with a culture in which ‘diversity’ conquers all.

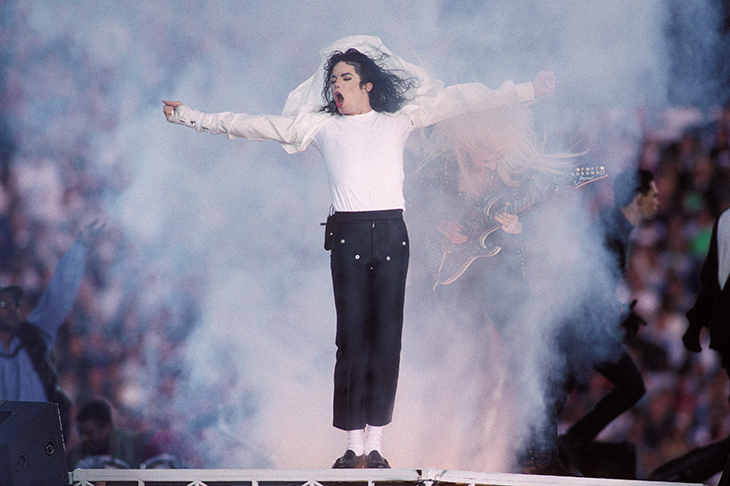

Why does it follow that, because an artist or performer is an appalling human being, his work should be banned? Speaking at Oxford in the late 19th century, Paul Verlaine introduced himself thus: ‘Je suis Paul Verlaine — poète, ivrogne, pédéraste.’ His work survived. Yet nearly a century and a half later, Michael Jackson has his music banned by the BBC.

‘The Westminster Strand’ sounds like a horror story, and so it is. It describes that aspect of the work of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA) which deals with cases of paedophilia in politics and government. It is also the reason for IICSA’s very existence: the inquiry was set up in a panic by Mrs May and David Cameron after Tom Watson abused his membership of the House of Commons to allege the existence of a paedophile ring in Downing Street and Westminster which later turned out not to exist. This latter-day Titus Oates is deputy leader of the Labour party. I hope IICSA — which is concerned with process, not individual accusations — will investigate how on earth this could have happened. If it does, it would then, logically, close itself down.

I am never sure what I think about tax havens. On the one hand, there is something terribly depressing about places whose raison d’être is tax avoidance. On the other, what the EU calls ‘unfair tax competition’ is better described simply as ‘tax competition’. It would be a very bad thing if powerful nations could abolish competitive pressure to keep taxes down. Whatever one thinks of them, tax havens themselves have laws. In the case of the Crown dependencies, the Isle of Man, Guernsey and Jersey, they are ancient entities, governed by the laws passed by their own parliaments, not by the House of Commons. As was also shown by the recent attempt to override Northern Ireland’s devolution in order to permit abortion there, there is a new, woke imperialism which disdains existing constitutional arrangements in the interests of higher virtue. This righteousness supposedly trumps the rights of Man (and Jersey and Guernsey). How dare the Commons interlope in this way? Man’s parliament, the Tynwald, is about 300 years older than ours.

The transgender question is acute in women’s sport because, to most women competitors, it understandably seems little more than cheating. In my 1960s childhood, I remember being told that something similar had come up in the London Olympics of 1948. The authorities, made suspicious by the prodigious strength of Soviet women athletes, had insisted on sex tests. At this point, the Soviet ‘ladies’ withdrew en masse and took refuge, with diplomatic immunity, in the country house which the Russians to this day possess, just over the Kent border from where we live. It was an early Cold War issue. If it were to occur today, Stalin’s men in skirts would not have to hide, but could instead assert their rights to the gender of their choice. An odd sort of advance for freedom.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in