When lists are compiled of our best and worst prime ministers (before the present incumbent), the two main protagonists of this book usually feature, holding the top and bottom positions.

Attempts are periodically made to revise these verdicts, most recently in John McDonnell’s description of Churchill as a villain; and by Robert Harris’s sympathetic portrayal of Chamberlain in his thriller Munich. By and large, however, the general view of the two PMs remains fixed: Churchill was a hero who saved his country and arguably freedom and democracy worldwide, while Chamberlain was a purblind and arrogant fool who let Hitler stomp his jackboots all over him.

The revisionists who want to change those verdicts will get little comfort from this absorbing study of appeasement, the flagship policy of Chamberlain’s woeful premiership. Tim Bouverie has cast his net wide in telling the story, successfully melding the escalating acts of aggression by Europe’s Nazi and Fascist dictators abroad with the reaction to these events in Britain.

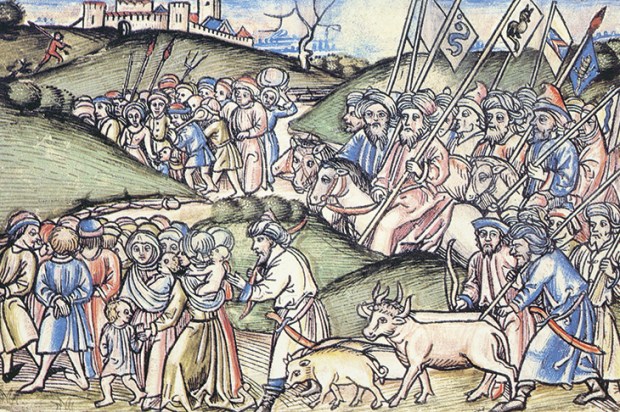

What is striking about Bouverie’s gripping narrative, as a distant cloud in the sky escalates into the thunderheads of looming war, is the complacent, escapist inaction, not only of the ruling political establishment, but of the general public at large. As Hitler’s appetite grew keener with every chunk of real estate swallowed — the Rhineland, Austria, the Sudetenland — so Britain sunk deeper into the big snooze.

There were good reasons for the nation shutting its eyes to unpleasant reality. The Great War had left such a gaping wound that none relished the prospect of a rematch. The traditional British sympathy for the underdog and sense of fair play had resulted in an uneasy feeling that poor little Germany had been too harshly treated at Versailles. The great depression had focussed minds on jobs at home rather than what was happening across the Channel.

Disturbingly, as Bouverie shows, admiration for such Nazi ‘achievements’ as ending unemployment, building autobahns and invigorating German youth was widespread — and not only confined to aristocrats who saw Hitler as a useful bulwark against Bolshevism. Eyes wilfully closed to the criminal nature of the regime, the open persecution of the Jews and the implications of Hitler’s relentless re-armament. Who was going to be on the receiving end of those fleets of tanks and warplanes? Few asked.

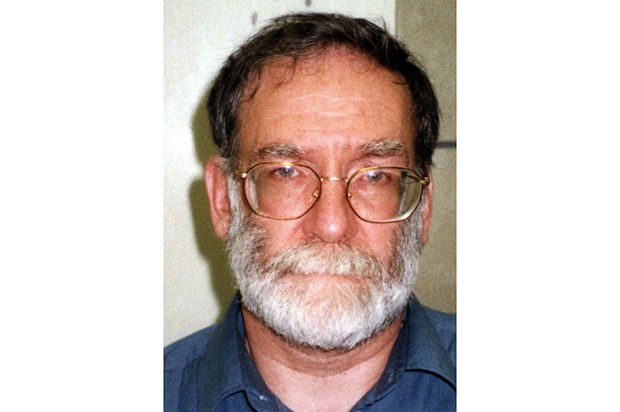

One who did was Winston Churchill. But since he had been wrong on so many issues — Gallipoli, the Gold Standard, Indian independence and the Abdication — too few noticed that he was right about this big one. Out of office and deeply distrusted by most of his Conservative colleagues, he was almost literally a lone voice crying in the wilderness.

And so, in Churchill’s words, the locusts devoured the years. Prime minister Stanley Baldwin, uninterested in foreign affairs and anyway convinced that ‘the bomber will always get through’, refused to spend money on defence. He was succeeded in 1937 by Neville Chamberlain, an able health minister and chancellor, but cursed with coming to power at a moment when foreign affairs were all that mattered.

Chamberlain’s combination of malicious conceit, stubborn obstinacy and invincible ignorance of ‘faraway countries of whom we know nothing’ proved lethal for his own appeasement policy, and almost did for the nation too. Right up to and beyond Munich he believed in Hitler’s good faith and his own propaganda portraying him as the man who had secured peace.

Chamberlain’s contemporary apologists argued that Munich brought the nation a year’s breathing space which was belatedly used for frantic boosting of air defence and fighter aircraft production. But Bouverie makes clear, using Chamberlain’s own unguarded letters to his sisters, that the PM naively clung to his illusions until Hitler’s invasion of Czechoslovakia in March 1939 finally — and much too late — revealed appeasement as wishful thinking.

Bouverie has written a searching, wide-ranging, and above all readable chronology of a shameful era of British history, when the elite and the general public were at one in pursuing and supporting a course of inaction that seemed sensible and pragmatic at first, but eventually proved almost fatal to the nation’s survival. It is a very cautionary tale.

If there are any parallels to be drawn with the nation’s current predicament vis-à-vis an overbearing and bullying European power, it is perhaps in the words of Baldwin’s cousin Rudyard Kipling: that if you keep paying the Danegeld, you will never get rid of the Dane. Or, as Churchill put it: ‘An appeaser is one who feeds a crocodile, hoping it will eat him last.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in