The best double acts — Laurel and Hardy, Gilbert & George, Rodgers and Hart — are often made up of two quite different personalities. So it was with the painters William Nicholson and James Pryde, who worked together under the names of J. & W. Beggarstaff. Their similarities and dissimilarities are the subject of a highly entertaining exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

Nicholson (1872–1949) and Pryde (1866–1941) are sometimes dubbed the ‘Beggarstaff brothers’. They weren’t really siblings, but they were brothers-in-law. At the age of 21, in 1893, Nicholson eloped to Ruislip with Pryde’s sister Mabel. The couple set up house in an ex-pub, the Eight Bells at Denham, and their baby Ben (later to become a notable artist himself) was born the following year.

The collaboration between Pryde and Nicholson — the starting-point of the exhibition — began shortly afterwards. It didn’t last long, petering out before the end of the decade. But during those years Nicholson and Pryde produced a series of large scale-poster designs like nothing else in British art of that time.

These consisted of simple bold shapes made by gluing down pieces of coloured paper — an early type of collage. The best of the Beggarstaff posters — ‘Don Quixote’, for example, and ‘Children Playing’, both 1895 — have the oomph and impact of contemporary Parisian graphic art by Toulouse-Lautrec and Pierre Bonnard.

Which Beggarstaff did what is unclear. ‘One of us gets an idea,’ Pryde told the Idler magazine in 1896. ‘We talk it over, the other suggests an addition, the matter is reconsidered.’ Edward Gordon Craig, the actor, director and theatrical designer who commissioned the very first joint effort, a poster for Hamlet, thought Nicholson did most of the work.

Pryde probably contributed a sense of scale and atmospheric theatricality. Those, at any rate, were the qualities of his independent works. It is to these and to Nicholson’s later pictures, plus some comparative pieces, that most of the Fitzwilliam show

is dedicated.

Nicholson remembered that the two men chose the pseudonym ‘Beggarstaffs’ because it seemed a suitably ‘good, hearty old English name’. Perhaps it appealed particularly to him. Those qualities — heartiness, antiquity and Englishness — were certainly ones Nicholson valued, as is obvious from the series of brilliant woodcuts he published in the late 1890s.

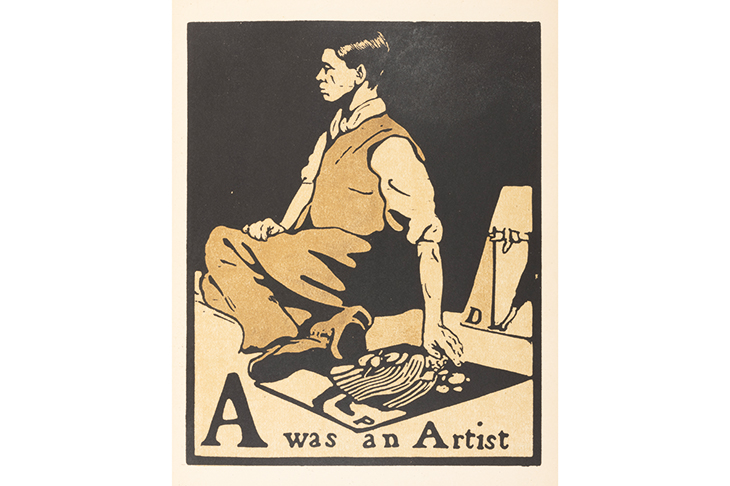

These combine the wit and succinct precision that he shared with Manet and Whistler with a sense of character which has more to do with Dickens or Thackeray. The first of Nicholson’s illustrated books was An Alphabet (1897), in which ‘A was an Artist’ is a self-portrait as a pavement artist and

‘B for Beggar’ a portrayal of Pryde wrapped in a ragged cloak.

Pryde’s inspirations were equally nostalgic and romantic, but, understandably, since he came from Edinburgh, more Scottish. He was less interested in people than in scenes — Piranesi-like ruins, crumbling Mediterranean townscapes — resembling stage sets (an idiom that Nicholson, evidently still looking at his old friend’s work, attempted too).

Pryde’s series The Human Comedy was inspired by an early memory of Mary, Queen of Scots’ bedchamber at Holyrood. The final canvas, depicting a surreally enormous and shadowy four-poster, stood unfinished in his studio for years before his death (drink and melancholy got him in the end).

The exhibition gives considerable space to Pryde, which is good since he is an intriguing and neglected, if repetitious, artist. But you feel you’ve seen enough. It’s different with Nicholson, a much greater painter — better, perhaps, than his famous son Ben. His true achievement is slightly underplayed by this exercise in compare and contrast. Sometimes one partner in a duo goes on to even greater things. Think of Fred and Adele Astaire.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in