‘It is no easier to make a good painting,’ wrote Vincent van Gogh to his brother Theo, than it is ‘to find a diamond or a pearl.’ He was quite correct. Truly marvellous pictures are extremely rare. To make one, Vincent went on, you have to ‘stake your life’ (as he, indeed, was doing).

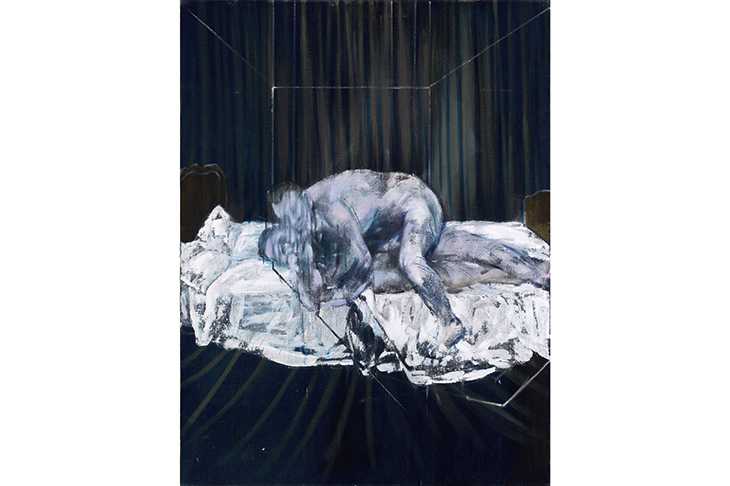

Well, there is just such a jewel of a painting — only one by my count — in Francis Bacon: Couplings, an exhibition at Gagosian, 20 Grosvenor Hill. In some cases, the title of the show is literal. Several pictures depict two naked men in a ferocious sexual tangle. As a subject, this is perhaps still slightly daring today; it would have been astonishingly outré in 1953 when Bacon produced this dark masterpiece, ‘Two Figures’.

Its imagery was borrowed from a photograph of wrestlers in action by Eadweard Muybridge. But there is no suggestion in the painting that these naked men are taking part in a sporting contest. Bacon transferred the action to a bed. The lower figure’s mouth is pulled back in a spasm, whether of agony or ecstasy, it is hard to say.

Unsurprisingly, it was unsold when Bacon’s exhibition came to the end of its run, so the young Lucian Freud was able to buy it for £80. In comparison with Bacon’s current auction record — $142.4 million — that certainly seems like a bargain (though Freud liked to point out that 80 guineas was quite a sum in 1953).

There are several good Bacons elsewhere in the exhibition — ‘Two Figures in the Grass’ (1954), and ‘Painting’ (1950) — in particular. But none of them has the punch of the wonderful but fearsome ‘Two Figures’. Quite rightly the Gagosian gives it a room to itself.

What is the quality that makes it ring out? Bacon himself didn’t quite know how he achieved his results. He would work and rework a particular idea in the hope that eventually the magic would happen, and he’d paint a picture that satisfied him. Occasionally it did, partly — he insisted — by sheer chance.

Bacon once told an interviewer: ‘I can’t explain my art, or even my working methods. It’s like the person who asked Pavlova, “What does the dying Swan signify?” and she answered: “If I knew I wouldn’t dance it!”’

There is an eye-witness account of Bacon painting numerous pictures of naked men in the grass — much, presumably, like the one in the show. Then one day he slashed 20 or so of these canvases to ribbons. Presumably, the works at Gagosian survived a similar winnowing process.

The visitor will search in vain for paintings as rare as diamonds in the exhibition of work by Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962) at Tate Modern. Goncharova was one of the most prominent artists in Moscow during the avant-garde ferment in the years leading up to the first world war. Like other Russian experimental artists, she charged through numerous movements and groupings: some evidently hybrid, as their names reveal — ‘cubo-futurism’, for example. Essentially, what she was doing in those years was taking the latest thing from Paris — by Gauguin or Picasso — and adding folksy ingredients such as motifs from traditional Russian icons and textiles.

There’s nothing wrong with this strategy; everybody has their influences. The trouble was that her pictures — though energetically painted, boldly designed and cheerily colourful — don’t have that extra ingredient that makes a painting pop off the wall and stay in your memory. Despite all the scything brushstrokes and simplified drawing, Goncharova seems to be wrestling against an inner impulse to produce nice, pretty pictures. The giveaway is the slightly soppy faces of her people.

Goncharova was better as a designer than a painter — and best of all at theatrical sets and costumes for the Ballets Russes (she collaborated with Stravinsky on Les Noces, among other projects). For this reason, the last room of the exhibition — containing not only her designs but many actual costumes — is by far the best.

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, the Hungarian modernist whose work is on show at Hauser & Wirth, was a younger contemporary of Goncharova. He, too, doesn’t seem entirely a painter by talents, but something else — a designer perhaps or an architect. The most striking exhibit is his ‘Light Prop for an Electric Stage’ (1930), a gleaming machine vaguely resembling a fantastically overelaborate piece of kitchen equipment, perhaps intended to roll pasta or make bread. And the most enjoyable thing on show is a film the artist made of this contraption in action.

For the rest, there is a transparent sculpture, as well as abstract paintings and even — a more recondite category — abstract photographs. But, although this is an enjoyable and worthwhile exhibition, no pictorial diamonds are on view here either.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in