‘The possibilities of paint,’ Frank Bowling has observed, ‘are endless.’ The superb career retrospective of his work at Tate Britain demonstrates as no words could that he is correct, and that the obituaries of this perennial medium — so often declared moribund or defunct — are completely wrong. This presents more than half a century’s virtuoso exploration of what pigment on canvas can achieve.

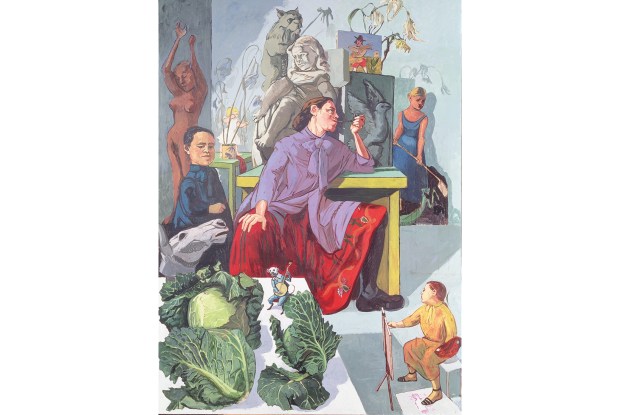

After his first decade of work, Bowling (born 1934) became what is called an abstract artist. But that is a vague and unsatisfactory category. His early, figurative pictures such as ‘Cover Girl’ (1966) could be labelled ‘pop’. It features an image of a Japanese supermodel garnered from the front of the Observer colour supplement — plus a very different silkscreened photograph of a shop in New Amsterdam, Guyana, which was the artist’s childhood home.

In other respects, however, the picture — like all good ‘figurative’ paintings — is quite abstract, mixing sharply edged stripes and soft, cloud-like patches of colour. Later on, after he had ostensibly crossed the frontier into abstraction, Bowling’s pictures still continued to be powerfully evocative of the physical world. ‘Towards Crab Island’ (1983) has the feel of a waterland by Monet. The Great Thames series from the late 1980s, painted in a Docklands studio, suggests the ooze and ripple of the river nearby.

The ten-foot high multi-hued waterfall of ‘Aston’s Plunge’ (2011) has something of the sublimity of a late Turner (though in a much funkier vein). Bowling is aware of his great predecessors. He has talked about the challenge of working in London, ‘Turner’s town’. A touch of Constable is visible too, side by side with Mondrian and Jackson Pollock.

Pairing the Bowling show with Van Gogh in Britain, downstairs at Tate Britain, is unexpectedly apt. Of course, the Dutch master made the journey from the cool north to the hot colourful south and dreamed of going further, to the tropics. Bowling journeyed in the opposite direction, sailing from what was then British Guiana to Britain, where he arrived in 1953.

What makes his trajectory unique, however, is that he then moved on to the New York of Andy Warhol and Barnett Newman. I can’t think of another artist who has inhabited all three of these environments: Caribbean heat, foggy London and modernist Manhattan. Bowling’s majestic ‘map’ paintings from around 1970, in which the outlines of the continents of Africa and South America emerge faintly from sumptuous oceans of colour, perhaps hint at his personal Odyssey.

Another link with Van Gogh is that both he and Bowling are enthralled by the possibilities of paint: the rich glutinous substance itself in all its variations of thickness and thinness, transparency and opacity. At various times Bowling has — in addition to applying the stuff in a conventional manner with a brush — thrown it, flicked it like sea spray, and used it to stain his surfaces in translucent veils. The zinging red, blue and yellow of ‘Tony’s Anvil’ (1975), gyrating wildly like the graph of an earthquake, were produced by controlled pouring.

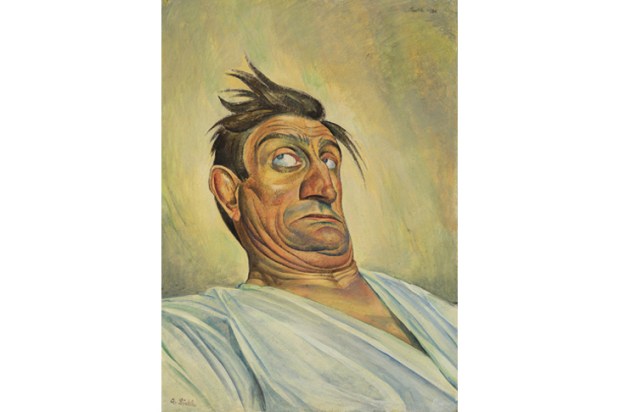

Master though he clearly is, Bowling has been neglected for prolonged periods. The work of Lee Krasner, another important, long-overlooked abstract painter, is on show at the Barbican. In both cases, vagaries of art fashion have been partly to blame. Bowling turned to abstract painting just as it was going out of style. Krasner (1908–84) found herself as a gestural abstract expressionist exactly when that idiom was being replaced.

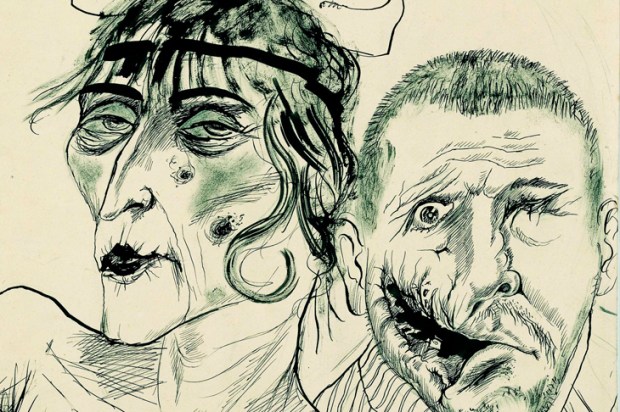

Krasner was probably both helped and hindered by being married to Jackson Pollock, one of the greatest innovators in 20th-century painting. When they met, she was the more senior artist. But it was Pollock who made the inspired leap into abstract expressionism: his flying pigment free, rhythmic and pulsing all over the canvas. It took Krasner ten years to assimilate this revolution. She described how she was completely blocked, unable to produce anything but ‘grey slabs’. When she did break through, it was by first physically cutting up her own work, then recycling it in the form of collage — thus forcing looseness and freedom on herself.

In 1956 Krasner was just getting going, when Pollock was killed in a car crash. Grief-stricken, afflicted with chronic insomnia and working in Pollock’s old studio, she battled on. A few years later she produced her masterpieces — ‘Polar Stampede’ (1960), for example, and ‘Another Storm’ (1963) — powerful pictures, suggestive of a wild sea breaking over rocks, throwing up plumes of spray.

By that date they looked a little passé to the art world of the day. But what seemed cutting-edge in 1960 is now irrelevant. Today’s newspapers, it is often said, are the first draft of history. In the same way, contemporary judgments are only an early draft of art history — and equally subject to being revised. Each of these exhibitions does just that.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in