The art-history books will tell you that sometime around 1912, Picasso invented collage, or, actually, perhaps it was Braque. What they mean is that sometime around 1912 a man of sufficient standing took up a technique that had been quietly practised in largely domestic spheres by a largely female army of amateurs, and applied it in his own work. Cue the universal astonishment of observers who pretended they had never seen such a thing before.

This narrative has been recycled ever since, assuring us that the collage techniques that shaped the language of dada, surrealism and all the other isms that made up modernism, as well as pop art and even today’s Photoshop-driven design, all emanated from that one original spark of paper-sticking cubist genius.

So thank heavens that the National Galleries of Scotland’s new exhibition, Cut and Paste: 400 Years of Collage, is here to set the record straight. A sprawling festival of collage, papier collé, découpage, photomontage, photocollage, cut and paste, scrap work, mosaic work — call it what you will — fills both floors of the gallery and effectively resets the chronology.

The rediscovery of all these unheralded practitioners of premodernist collage is exciting. The range of collage-esque techniques that were practised over the centuries before Picasso unfolds like a museum of curiosities. Complicated 16th-century anatomical flap books vie with similar constructions that advertise how Humphry Repton might improve your Georgian parkland. Elsewhere a creepy, outsize die-cut baby hovers alarmingly over a stuck-down arrangement of posies and disembodied hands.

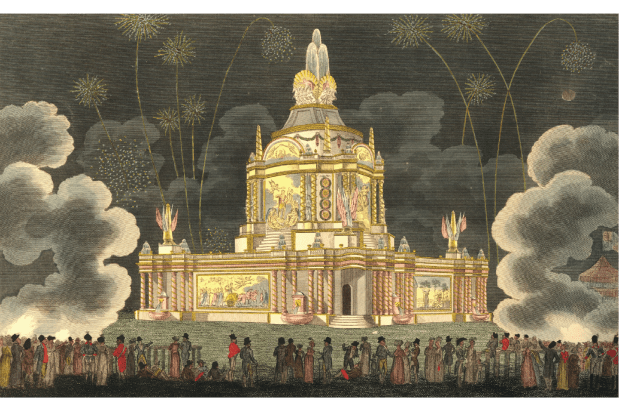

Even better are Mary Delaney’s still quite astonishing botanical collages, which pop off the walls with a vibrancy that belies the fact they were created 250 years ago from tiny shards of hand-tinted paper by an ‘amateur’ artist in her seventies. Nearby, elaborate silhouettes and stage-set portraits, decorated home furnishings — including a screen covered with pictures reputed to have been pasted there by Charles Dickens — and ‘paper transformation’ constructions that become nocturnal scenes when backlit by a candle all indicate the rampant variety of creative ways with cut paper that emerged from people’s homes as soon as the materials became readily available.

By Victorian times, paper was everywhere. Scrapbook kits, Valentine card kits, photographic cartes-de-visite and all manner of decorative papers became fixtures in wealthy homes, and cutting it up became an obsession. Presages of modernism abound. Photomontage is used extensively to create space-defying group portraits or deceptive illusions. A scrapbook of sliced-up words and portraits by Mary Watson, from 1821, reads like the chance poetry practised 100 years later, and looks like some punky contructivist graphic.

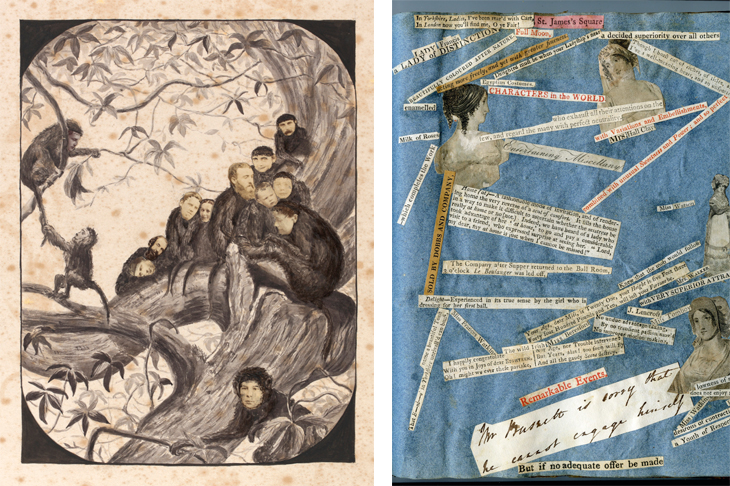

George Smart uses cut-out newspaper in his vignettes of early 19th-century Sussex life, just like a cubist. Take that, Picasso. Meanwhile, Kate Gough’s peculiar photo-and-ink montages of shrunken children and monkeys with human heads are pure 1870s proto-surrealism: Max Ernst, born before himself.

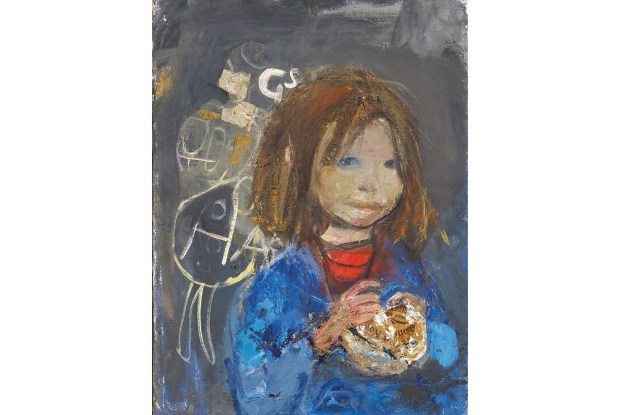

There is plenty here like this — inventive, imaginative and often made by women. Denied the opportunity to paint or sculpt, well-to-do ladies went to town with scissors and glue. That the work could be startling in its skill and originality meant nothing, though. It was dismissed as an artform and explicitly barred from the Royal Academy.

By the time the cubists took up scissors to toy with abstract cut-outs and trompe-l’oeil commercial patterns, the potential of collage had been well established by its domestic progenitors. The 20th century just brought the methods to mainstream art, embraced by a new generation of artists who had grown up in cities so plastered with advertising they were ever-evolving, real-life collages.

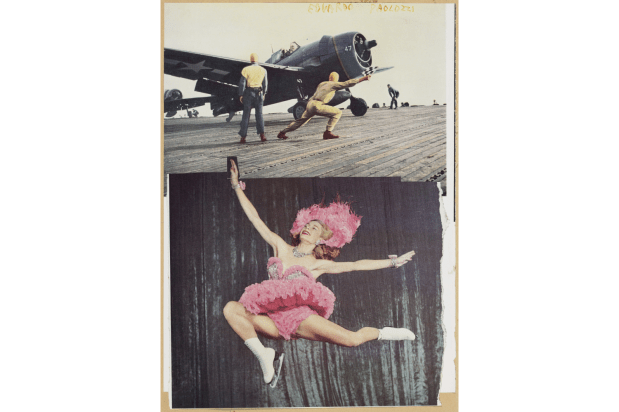

The fast-paced methods and instant effects of collage soon became the preferred vehicle for expressions of rebellion, lending a cheap, readymade aesthetic to visual protest from the first world war onwards. The dadaists began their satirical collages in Germany during that war, inventing the term ‘photomontage’, if not the technique, and kept at it for the next two decades. Seven of John Heartfield’s photomontage assaults on Nazism, created for mass circulation rather than the art gallery, are displayed here. The ferocious rebuke of his distorted realism is still as savage today.

But collage was also well suited to the consumerism-fixated art of Eduardo Paolozzi, Peter Blake and Andy Warhol. Robert Rauschenberg’s approach was entirely dependent on the cut-and-paste effect, as was Robert Motherwell’s. Cheap, fast, easy to construct and endlessly recyclable, collage became a dominant aesthetic in the 20th century, shaping everything from Picasso’s flat, fragmented paintings, through Warhol’s multiples and the graphics of 1970s protest art, to our modern, mouse-clicked designs.

Interestingly, though, when seen in the context of a fuller history, the cut-out shtick feels a little tired by the time the pop artists appear. Blake’s Sgt. Pepper artwork is grand, but it’s nothing George Washington Wilson wasn’t doing in Aberdeen back in 1857. There are a number of forgettable post-war collage works in this exhibition that feel like yet another variation on a rehashed trope. The late-career flat-colour cut-outs of Matisse, on the other hand, diverge from the general obsession with the found image. Untrammeled by contemporary photography, his ‘drawing with scissors’ technique remains fresh today.

Also standing out from the soup of post-war photomontage is Gwyther Irwin’s large scale ‘Collage No. VIII’. More a piece of anti-collage, it is made from peeled-back layers of poster and resembles the obscure remains of a medieval vellum manuscript or a decaying shroud. Substantial and meditative, it also recalls the paintings of Antoni Tapies, which, often heavily collaged with paper, fabric, dirt or hair, are a regrettable omission.

There is good stuff among the contemporary exhibits, with some lightly sculptural, rhythmic and elegant works by Fred Tomaselli and Lucy Williams that expand the definition of collage. Jean-François Rauzier’s montage of pictures from the National Gallery demonstrates the power of digital technology. This is the visual language of our time, and Rauzier’s immensely detailed, digitally stitched photographic print feels like some kind of metaphor for the vast potential of the image in the age of Google.

The Chapman brothers’ more traditional but shamelessly bizarre collaged perversions of original Goya prints, titled ‘The Disasters of Everyday Life’, are also absorbing. The juxtaposition of unexplained modern pictures and Goya’s glowering backdrop embodies Paolozzi’s definition of collage as an exercise in ‘introducing strange fellows to each other in hostile landscapes’.

Of course, by gluing pictures on to original artworks, the Chapmans are merely following the women who, during Goya’s lifetime, were doing exactly the same thing to paintings by Watteau and Boucher in the court of Marie Antoinette. Let them cut and paste.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in