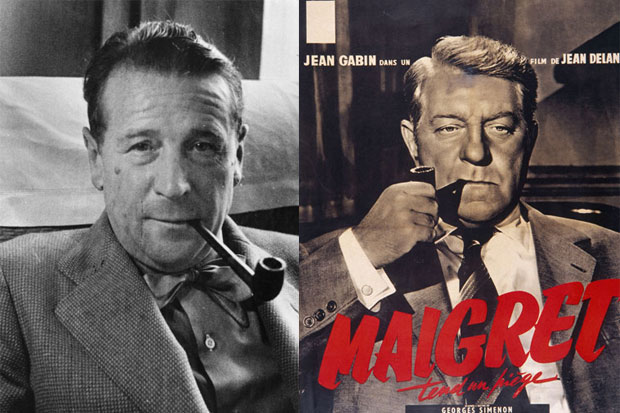

Georges Simenon, creator of the sombre, pipe-smoking Paris detective Jules Maigret, pursued sex, fame and money relentlessly. By the time he died in 1989, he had written nearly 200 novels, more than 150 novellas, several memoirs and countless short stories. His demonic productivity and the vast sales and fortune it brought him were matched by a vaunted sexual athleticism. Simenon claimed to have slept with 10,000 women. (‘The goal of my endless quest,’ he explained, ‘was not a woman, but the woman’ — which is French for wanting lots of it, very often.) It was not love-making, but a desire for brute copulation that drove Simenon to demand sex at least once daily of his wives, secretary and housemaid-mistresses. How he found the time to write the Maigret books is a matter for psychoanalysis. (Simenon described himself, without irony, as a ‘psychopath’.)

On the 30th anniversary of his death on 4 September, Simenon continues to be read and enjoyed. Although he dismissed his 75 romans Maigret as ‘semi-potboilers’, they are unquestionably literature. ‘In 100 years from now,’ Ian Fleming told him in 1963, ‘you’ll be one of the great classical French authors.’ Like the 007 extravaganzas, the books were written fast, without outline and hardly corrected at all. Simenon demanded silence as he set out to write one Maigret adventure a week. When Alfred Hitchcock telephoned one day, he was told: ‘Sorry, he’s just started a novel.’ ‘That’s all right, I’ll wait,’ came the reply. A one-man fiction factory, Simenon despised the Paris literary establishment and what he called literature with a ‘capital L’.

Over a period of six years, at the rate of one a month, Penguin have been issuing new translations of all the Maigret novels. The project is now almost complete, and not before time. The uneven quality of earlier translations, where endings were sometimes altered and the register was at times jarringly American (‘Maigret had gotten into the habit’), was unfortunate. The 11-strong team of Penguin translators, among them the late Anthea Bell, have restored a stylistic brilliance to the romans Maigret.

With rare narrative verve the books conjure the workaday rhythms and guilty secrets of Paris and small-town France. Simenon’s is a world of second-class hotels and third-class railway carriages, of drifters, bargemen, tarts and luckless creditors. His interest was not in intellectuals or master criminals but in his beloved ordinary people — les petits gens. Ordinary people are driven to ordinary acts of violence and social outrage. Criminals look like us, Simenon seems to be saying. His motto, ‘comprendre et ne pas juger’ (understand and judge not), is also Maigret’s.

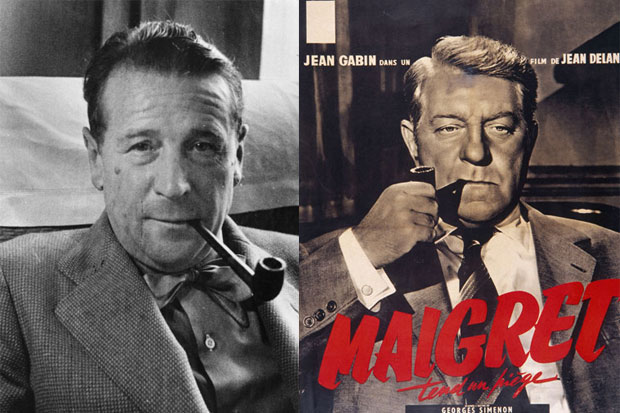

Maigret’s is, triumphantly, a search for understanding. The earthily dependable flic in his trademark velvet-collared overcoat and bowler hat is presented as a neutral observer, who looks on crime with an unbiased curiosity. The sense of complicity between criminal and policeman is omnipresent in the books. Strikingly, Maigret compares his role with that of a priest or ‘mender of destinies’. In The Saint-Fiacre Affair, translated by Shaun Whiteside, Maigret’s almost sacerdotal knowledge of the human soul is evident as he draws on childhood memories of communion wafers and ‘the secret of the confessional’. An elderly woman is murdered at Mass; Maigret seeks to understand why.

Born in the Belgian city of Liège in 1903, Simenon said he had a ‘middle-class soul’. Maigret is a bourgeois adrift in a murky underworld but, unlike his creator, he is dutifully uxorious. Madame Maigret pampers him like the needy man he is. (‘Men, they’re all the same!’) Alsatian-born, she serves him cassoulet and is aware of his many dislikes (whisky, champagne, calf’s liver, central heating). He is an only child. Madame Maigret calls him ‘Monsieur Maigret’ when she wants to tease; he can be extraordinarily overbearing. (‘Now, please will you fill a pipe for me and plump up my pillows?’)

His devotion to his wife is something that his creator clearly envies. The Maigrets have a holiday home in the Loire; in Paris they enjoy quiche suppers at an Alsatian restaurant near their flat on Boulevard Richard-Lenoir. (‘What’s the point of being Alsatian if you don’t know how to make quiches?’ Madame Maigret demands.) Perhaps it is fortunate that they have no children; Simenon’s much-loved daughter, Marie-Jo, committed suicide in 1978.

No fewer than 10 Maigret novels were published in 1931, with another seven the following year. (The last, Maigret and Monsieur Charles, appeared in 1972.) Pietr the Latvian, the first in the cycle, translated by David Bellos, displays a faint anti-Semitism in its portrayal of ‘garlic-eating’ Jews. As a cub reporter in early 1920s Belgium, Simenon had written vitriolic anti-Jewish articles for the Gazette de Liège. He later repudiated them, but a taint of Jew-baiting remains. (‘Jews usually have sensitive feet,’ Maigret tells his wife in The Madman of Bergerac. ‘And they’re thrifty.’) During the German occupation Simenon lived in seigneurial self-sufficiency in the French countryside; after the war, fearing charges of collaboration, he spent ten years in America. At some level, Simenon was a morally dubious man.

Impressively, the Maigret adventures show little sign of haste or overstrain in the writing. Simenon confessed that he typed many of them while half drunk. (He was intermittently alcoholic.) Unsurprisingly, they are awash with quantities of Calvados, Vouvray, Armagnac, Pouilly, caraway-flavoured kummel, pastis and rosé. Maigret is at times ‘glassy-eyed’ from too much Vermouth or else wretchedly hung over. In the early books he is a casually conceived figure with a detachable shirt collar, trouser braces and a dark ministerial suit. He becomes the archetypal fictional detective of the 20th century and the template for Inspector Morse, Kurt Wallander and any number of sternly pensive sloggers on the beat. The pipe is an essential prop. Maigret plugs it with tobacco when he wants to appear informal in the interview room. He carries at least two pipes in his pockets at all times. (Sometimes they overheat and sizzle.) His height is given as ‘1 metre 80’ — almost six foot. He is broad-shouldered, stubborn-browed and faintly bovine in appearance.

We learn more about Inspector (later, Commissaire) Maigret in Maigret’s Memoirs, an almost Pirandellian exercise in role-reversal where the detective talks in the first person about his creator’s perceived literary shortcomings. ‘Simenon likes to describe me as being heavy and grouchy,’ we read (in Howard Curtis’s translation), but the heaviness is frankly ‘exaggerated’. Maybe Simenon should re-write some of those descriptions?

Published in 1951, Les mémoires de Maigret is easily the funniest of the Maigret sagas. Scarcely a conventional detective, Maigret has no interest in Sherlock Holmes-style scientific deduction and prefers instead to operate by instinct. If pushed, he will resort to violence. Often he enters an abstracted, absent state or ‘trance’ while investigating — a sign that a breakthrough is imminent. In his fascinating biography of Simenon, The Man Who Wasn’t Maigret, Patrick Marnham relates that Maigret was based on the author’s adored father Désiré Simenon, an insurance salesman who died at the age of 44.

Georges Simenon died, aged 86, in his 36-room château outside Lausanne, a mausoleum residence where Jules Maigret would have felt ill at ease. Simenon is often and rightly read as an author who offers no hope. By the end of his life he had all the money and women he wanted, yet he was encircled by low spirits and the sadness of days gone by. His château had become his tomb. All that remained was Commissaire Maigret and his pipe.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in