Pedro Almodovar can sometimes be overly flamboyant if not out-and-out nuts — let us never talk about I’m So Excited! ever again — but his latest film, Pain and Glory, is wonderfully restrained and all the better for it. Partly autobiographical, it’s about ageing, and the reckoning that always comes with that — when you know you’ve had most of your life, how do you keep living it? — as told with the kind of humanity and sympathy and generosity you don’t ever see in a Tarantino film, say. (Are we still arguing about the Tarantino film or have we moved on?)

The film stars Antonio Banderas as Salvador Mallo, who is clearly meant to represent Almodovar, now approaching 70, at some level. Salvador is a famous filmmaker who has not written or directed anything for quite a while now. He is afflicted by physical ailments — a bad back; migraines; a choking syndrome — as well as mental ones, including depression and insomnia. He is on every type of pill. His suffers both physically and existentially. He does not imagine he will ever surmount his creative crisis, make another film, taste success again. The pain is wholly present but the glory? Yesterday’s news. None of this is ever spelled out but it’s all in Banderas’s sensitive, nuanced performance. It’s as if he’s somehow managed to dim the light in his own eyes.

Salvador is living a life of self-imposed seclusion. He has money and a housekeeper and the most terrific apartment. If you are into iconic 1960s pieces, as I am, you will be entirely transfixed. At one point he stands in front of a Vitra wall-organiser and I was quite annoyed I couldn’t see it properly. (Out of the way, Salvador, out of the way!) The apartment is also eye-poppingly colourful.

Almodovar does love colour and here it is used as contrast. The apartment is vibrant, whereas Salvador is decidedly not.

However, he is forced out into the world when he learns that a cinema has restored one of his early films and is about to show it. This leads him to make contact with Alberto (Asier Etxeandia), the actor who starred in the film 32 years earlier, but they fell out and haven’t spoken since. This reunion, in turn, leads him to reconnect with Federico (Leonardo Sbaraglia), his one-time boyfriend of three years whom he loved very much.

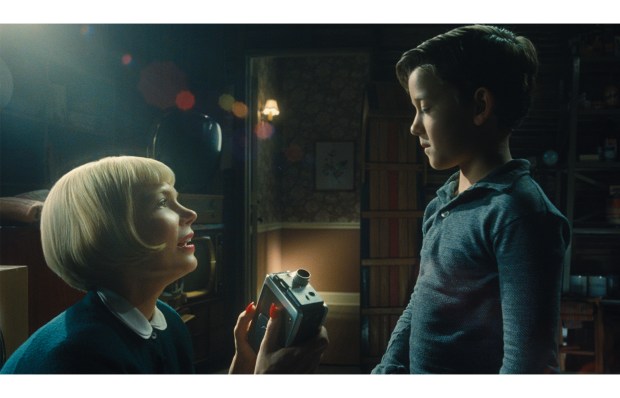

Meanwhile, desperate for relief, he develops a bit of a heroin habit which prompts a series of flashbacks to his childhood: washing clothes in the river with his mother (Penelope Cruz); moving to a small Spanish village and teaching local illiterates to read and write; first attending the cinema; experiencing the initial stirrings of erotic desire. These scenes are filled with all the hope and possibility that Salvador can no longer feel, and are based on many of the events from Almodovar’s own childhood.

I’ve made this all sound very sad and joyless and sour but there is also humour — his and Alberto’s Q&A at the cinema showing their film doesn’t quite go to plan — and it is all suffused with a beautiful tenderness. In particular, the scenes showing Salvador caring for his peppery, aged mother (now played by Julieta Serrano) before her death are especially moving. I shed a tear. But, ultimately, does Salvador have anything left to say? Does Salvador find salvation? You’ll find out. At the end.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in