It is bad enough when we learn that Santa Claus doesn’t exist. But later in life there comes another trauma, deeper still: when we discover that the beloved books of our childhood were in fact thinly veiled political theses, laden with economic metaphors and turgid intellectual ideas. My youngest child is not yet two. How long will it be until some clever clogs blunders into the nursery and tells her that The Wonderful Wizard of Oz must be read as an allegorical representation of the debate surrounding late 19th-century US monetary policy — or that The Very Hungry Caterpillar is an ode to Karl Marx?

Fierce Bad Rabbits sells itself as ‘an eye-opening journey through our best-loved picture books’ — a prospect some readers might, like me, resist. ‘Sometimes a tiger is just a tiger,’ as Judith Kerr protested when it was suggested that The Tiger Who Came to Tea was a story about the Gestapo. But this turns out to be a gem of a book, which turned all my reservations upside down. Clare Pollard has published five volumes of poetry, in which children’s literature is a recurrent theme. (Her latest collection, Incarnation, is described by one critic as a meditation on ‘fairy tales and news headlines and horrors’.) The idea for Fierce Bad Rabbits came to her when, as a new parent, she started revisiting the books she’d read as a child. A challenge arose: ‘Before I passed these stories on, shouldn’t I interrogate them a bit more thoroughly?’

One of the first in the dock is Beatrix Potter. Much has been made of the balance between sentiment and savagery in Potter’s work. (As old Mrs Rabbit warns her children about visiting Mr McGregor’s garden: ‘Your father had an accident there; he was put in a pie by Mrs McGregor.’) But Pollard focuses on the finer detail. We might not, for example, have connected the ‘subtle hints of humanness’ in Potter’s characters with the dark arts of premeditation. Hence Jeremy Fisher’s butterfly sandwich becomes ‘more grotesque for its preparation’.

But it is when we reach Alison Uttley’s Little Grey Rabbit books that we realise what lazy readers we have been. ‘The Little Grey Rabbit is saintly,’ Pollard writes:

In the first book, her servile relationship to Squirrel and Hare is deeply uncomfortable… She looks like their maid… Whether she is modelling the behaviour of a housewife or a servant, the message is that some people can be violated.

Uttley herself appears to have been made of sterner stuff. She hated comparisons with Potter, who she described as a ‘rude, old woman’; and in her diaries she dismissed her own illustrator Margaret Tempest as ‘a humourless bore’. When her husband committed suicide, aged 47, his relations feared he had been ‘nagged to death’.

Such are the biographical nuggets that make this book hard to put down. There is also a diverting section on Kate Green-away and John Ruskin, who met when she was 36 and he was 63:

As the years passed, it seems she drew more to please him than any audience of children. Many of her letters to him are illustrated with the languorous ‘girlies’ he so enjoyed gazing at.

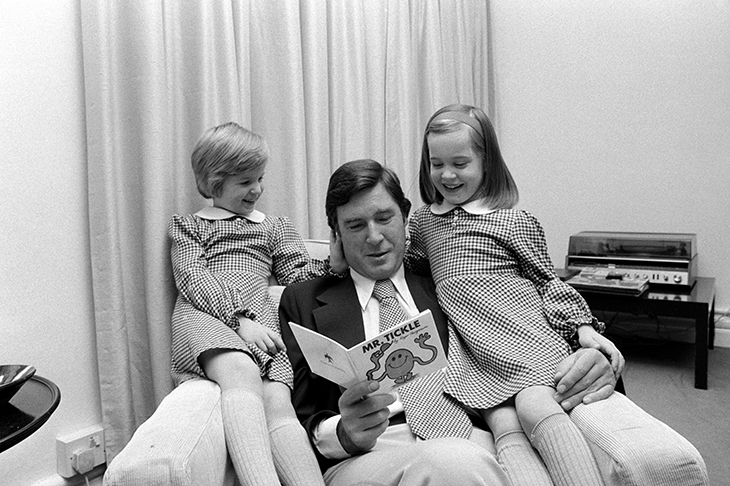

But Pollard’s primary interest is the texts, in which she manages to make her grown-up observations seem tantalisingly obvious. How, for example, could I have missed the Orwellian horror of Roger Hargreaves’s Mr Men books, in which Mr Neat and Mr Tidy make Mr Messy’s house as neat ‘as a pin’, then forcibly bath him until he is transformed into a faceless pink blob — ‘the basis of Mr Messy’s entire identity erased’. Other Mr Men characters suffer similar fates: ‘In story after story, they are normalised into namelessness.’ When I next pick up Mr Greedy, I shall remember that he is the personification of an abstract noun, and thus a clear rip-off of the medieval morality play. But in Hargreaves’s world there is no heaven to aspire to: ‘Only acceptance within the Misterland community.’

We might not agree with all of Pollard’s conclusions. (Does the fact that Babar the Elephant is seen procuring his shirts from a department store amount to ‘a kind of genesis myth’?) But the combination of vast scholarly research and witty writing makes for a thoroughly enjoyable book. By the final chapter, Pollard has managed to dissect all our favourite stories with her scalpel, while leaving their magic intact. She also solves a mystery that has long puzzled me. Why is it so often acceptable for characters in picture books to be eaten alive? ‘As a death, at least, to be eaten is not wasteful,’ she writes. ‘It has a kind of rationale to it. And being eaten leaves — usefully for the illustrator — no corpse.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.