MPs have a standard approach to political biographies, which falls into three phases: first, preliminary gossip about what will or won’t (always a lot more interesting) be in it; second, mildly salacious enjoyment of the usually tepid leaks and excerpts in the press beforehand; and third, once the book comes out, the inevitable furtive rummaging through the index to see if they get any mentions.

Stage three is hardly restricted to MPs, of course: William F. Buckley famously sent Norman Mailer a book with ‘Hi Norman’ inscribed in the index, knowing Mailer would look there first.

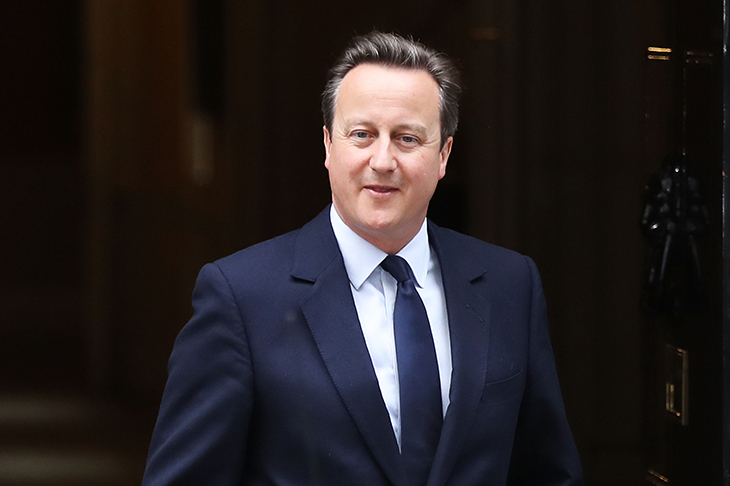

But I hadn’t got near stage three with David Cameron’s autobiography when my indefatigable assistant sent me a couple of spontaneous screen shots that made it clear that David had badly mis-remembered one small but significant episode: the 2012 rebellion over the government’s attempt to abolish the House of Lords.

Gentle reader, I led that revolting band of Conservative brothers and sisters — naturally, we called ourselves the Sensibles — and hitherto I have rebuffed numerous invitations to spill the beans as to what actually happened. My view has been that this was a most unfortunate, indeed un-Conservative, incident best left to posterity. But now that the sanctity of the lobby has been violated, the true story can be told; including a close encounter of the third kind between myself and the then prime minister.

Spectator readers are an educated bunch and, I have no doubt, are stern and unbending upholders of the British constitution. They have browsed the works of Bagehot, cosseted Coke and delved into Dicey. But the same was not true of the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government of 2010.

The prime minister had made his big, open offer, and had decided that the Liberal Democrat demand for a national referendum on the Alternative Vote was a small price to pay for a stable government with a large majority at a moment of national economic crisis. The deal was clear and well known. Conservative MPs would support the AV legislation in return for Liberal Democrat support on boundary reform, the historic neglect of which amounted to anti-democratic gerrymandering.

In May 2011, however, the AV proposal was rightly trounced by voters at the ballot box, by 68 per cent to 32 per cent. Immediately afterwards the government published a draft House of Lords reform bill, and set up a joint committee under the Labour peer Lord Richard to examine the proposals.

Over the following 12 months, several things became clear. The first was that the bill’s title was a misnomer. Few if any doubted that the Lords needed, indeed still needs, reform; but the bill effectively proposed its abolition, by turning it over time into an almost entirely elected chamber.

The second was that the joint committee was a shambles. Far from being an impartial chair, Lord Richard was known to favour an elected Lords. The membership was packed to support the bill.

Not only did the committee fail to reach a unanimous conclusion on most of the key issues — destroying any authority it might have possessed — but a group of its members, including six Privy Councillors, took the almost unprecedented step of issuing a minority report. None of this mattered, though, because the committee made two majority recommendations, and the government ignored them both.

The third was that there was serious concern about the bill from Conservative backbenchers. This had started early: with colleagues, I had presented a private letter signed by more than 40 Conservative backbenchers to the then chief whip on 18 July 2011, a full year before the bill got to the Commons. This argued for constructive reform, but unequivocally rejected an elected upper house. It was a very clear statement of intent, but unfortunately it too was ignored.

I had never voted against the government before. As for the other signatories, the vast majority were also not serial rebels but also loyal backbenchers — including six future cabinet ministers — who wanted to nip a potential constitutional crisis in the bud.

They knew that although our parliament looks like a bicameral institution, in reality it is not: it is basically unicameral, with a single deciding chamber, the House of Commons, and a secondary advisory chamber in the Lords, whose function is to examine and give sober second thought to legislation which is often rushed and under-scrutinised in the Commons.

The Lords is thus not in the full sense a legislative chamber. Nothing can become law unless the Commons wishes it so, the Lords never even sees money bills, and if absolutely necessary the Commons can pass legislation by itself, irrespective of the Lords. The Commons has the core legitimacy of election; the Lords the lesser legitimacy of established practice, expertise and effective process. Both are fundamental to our constitution.

But despite its limited powers, the Lords has often proven highly effective. With its enormous majorities, the Blair government was defeated just four times in the House of Commons over a ten-year period. Over the same period, it was defeated 460 times in the House of Lords. Which chamber did the better job of checking executive power?

Turn the Lords into an elected senate, however, and mark what follows. The new senate would start to act as a second House of Commons. It would inevitably become more party-political and less expert. The quality of legislation would fall. The senate’s emphasis would be on competing with the Commons, not on scrutinising and amending legislation.

But this is just the start of the problem. The point of elections is to confer power. Over time the new senate would argue that it had greater legitimacy than the Commons, since its members had electorates vastly larger than the 70,000-odd voters normal for MPs. Senators would feel they had a positive obligation to stand up to the Commons, just as MEPs started to throw their weight around after the European parliament switched from being appointed to being elected in 1979.

Today, when people elect their MPs they elect the government. That would no longer be true. Over time parliament would become more like the US Congress, marked by gridlock between the chambers, greater partisanship and poorer legislation driven by interest-group politics. The flexibility and balance of the British constitution, fragile but intact today and widely admired around the world for more than 300 years, would be destroyed.

The Lords bill finally came to the Commons in July 2012. Opening the debate, Nick Clegg made clear that if the bill was opposed in the House of Lords, the government would use the Parliament Act to drive it through.

The Labour party supported the bill in principle, but opposed the shortened timetable which the government had laid out in a so-called programme motion. Securing the programme motion was therefore crucial; otherwise the bill could be filibustered, creating endless delay and preventing the passage of other legislation.

All thus hinged on the votes of sensible Conservative backbenchers. These had been subjected to huge pressure, including the argument that if the Liberal Democrats did not get their way on the Lords bill they would kill the boundary reforms, a manifest breach of the agreement between the parties. (The Conservatives won the 2015 general election even so.)

Over the weekend the press speculated that a rebellion of 30 to 40 Tories would be enough to defeat the bill. So when on the first day of the debate I published a letter against the bill signed by 57 Conservative MPs, with more than a dozen further names withheld, the result was mayhem.

The temperature went up another notch later that day with the release of a devastating comment by Lord Pannick QC — famous now from his exploits in the Supreme Court — which stated that ‘the bill does not adequately address the central issue of constitutional concern’.

Faced with this twin political and legal challenge, on the following morning the government withdrew the programme motion, signalling the effective defeat of the bill. On the substantive vote itself, 91 Conservative MPs voted against the government. It was the largest rebellion by government MPs on the second reading of any bill since the second world war.

But for me the previous evening had included personal drama as well. As the vote was called, our rebel whipping operation had swung into action and I had moved in front of the No voting lobby so as to encourage MPs towards it.

David Cameron was clearly very angry about the scale of the defeat, his temper not helped by an email I had sent in good faith to wavering colleagues a few minutes before the vote, which argued that the largest possible rebellion would actually help the prime minister by killing the legislation outright. Directly after voting, he strode up and tore a strip off me while jabbing me in the chest with his finger, while I stood there gaping at this unexpected development. Little in my previous experience had prepared me for a sudden bout of energetic pectoral massage by the prime minister of the day.

Perhaps understandably, in his book David passes over this modest assault in silence. What is more telling, perhaps, is his insouciance then and now about the constitutional issues involved.

That insouciance is widely shared. One of the more striking ironies of the Brexit debate has been the number of well-known politicians — Nick Clegg, Andrew -Adonis and many others — who denounced the House of Lords as an undemocratic monstrosity in 2012, only to sing its praises after 2016 as a sober and expert chamber immune to the winds of populism, when they thought it could be used to delay or prevent the UK’s exit from the EU. Wisely, the Lords has declined to do so.

The British constitution is not perfect. But as this episode and the recent shenanigans over Brexit and the Fixed-Term Parliament Act of 2011 remind us, it possesses a deep inherited wisdom which — and this is not a fashionable thought — outstrips individual comprehension. It has evolved over hundreds of years as a means not merely to constrain democratic power but to defend it; from monarch and people alike. You meddle with it at your peril.

Perhaps we all need to spend a little more time with Bagehot, Coke and Dicey. We might avoid a few blunders, and — who knows — maybe even engineer some lasting and effective Lords reform as well.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in