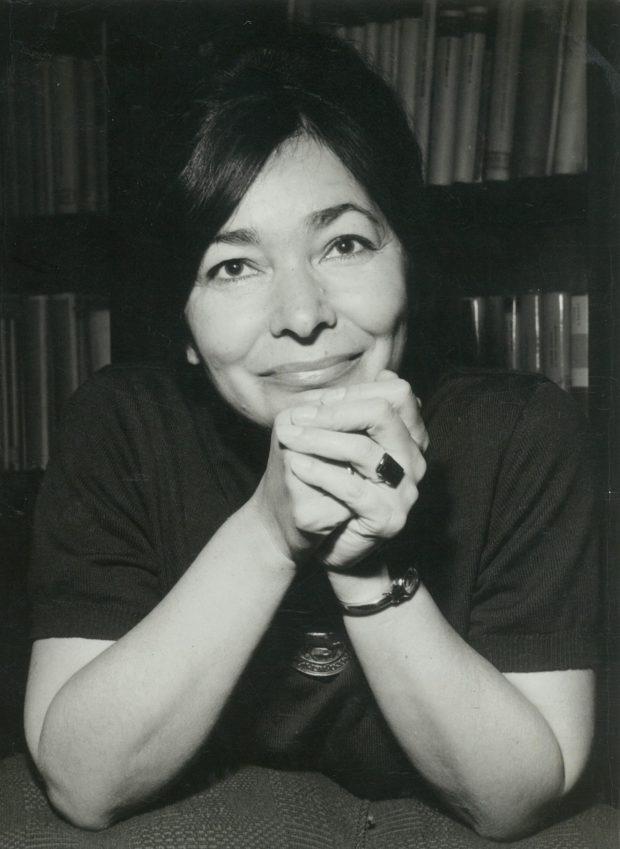

The story of how Hugo Vickers eventually tracked down the former Gladys Deacon, Duchess of Marlborough is almost as fascinating as how Gladys nailed her duke. Both were obsessions that began young, that of the 16-year-old Vickers when he read of ‘The love of Proust, the belle amie of Anatole France’, and was so taken that he wrote his first biography of her 40 years ago, and that of Gladys when at 14 she wrote (of the Duke) ‘O dear if only I was a little older I might “catch” him yet’.’

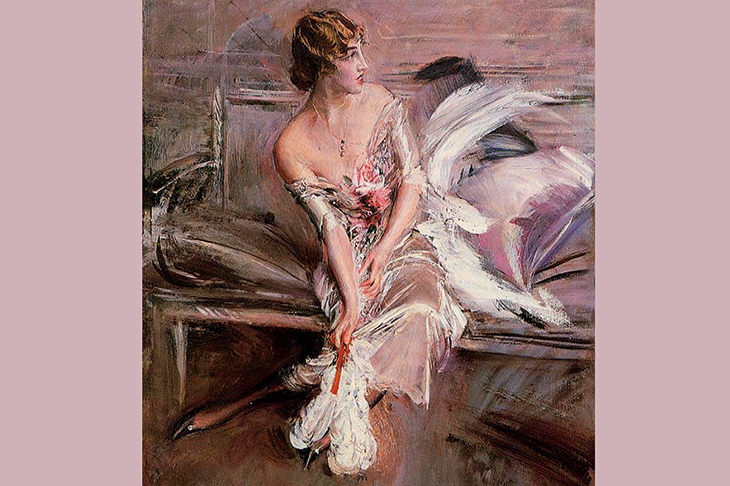

Gladys (born in 1881) was a star from the word go, extremely intelligent — her tutor called her a ‘brain genius’ — and avid to learn. At a time when ‘accomplishments’ such as sketching, singing and needlework were considered all the armoury a rich, well-born young woman needed, she emerged with seven languages, a wide general knowledge and a lifelong love of art, literature and poetry, as well as the exceptional beauty that would eventually become her downfall.

Over her hung an aura of scandal at one remove: when Gladys was 11 her father had shot her mother’s lover dead as he cowered behind the sofa. At the least, this meant a life jolted out of the norm. With her mother, she travelled round Europe, as she did so making a conquest of the noted art historian and expert Bernard Berenson as well as many others smitten by her charm and beauty. ‘Radiant’ was an adjective constantly applied to her.

She finally met the Marlboroughs at the turn of the century, fascinating them both. When she ‘did’ the London season of 1902, she was largely escorted by Consuelo, the Duchess, and when the Crown Prince of Germany fell in love with her, her name became known to everyone. Her success continued, with several dukes as well as less exalted suitors pursuing her.

Then, that autumn, came the fateful step that affected the rest of her life. Like so many beauties who complain of invisible flaws, Gladys found one — in her case a slight indentation between the bridge of her nose and her forehead — and decided to remedy it with the 1902 version of a tweakment, to achieve a museum-perfect Grecian profile. She had paraffin wax injected into the small depression — with disastrous consequences later.

Gladys was clearly somewhat unbalanced, and her behaviour at times outrageous, but such was her charm that she got away with it. She quarrelled violently with her sister and her social flibbertigibbet mother, but when her sister died — basically of meningitis — she was devastated.

She continued to ricochet round Europe, the list of her suitors growing longer and longer. Rodin sculpted her and Proust even got out of bed for her. But despite the entreaties of admirers and those of her mother — whose reputation and status would have been boosted by a ‘good’ marriage for her daughter — Gladys refused to tie herself down.

The injections of paraffin wax were now taking their toll on her looks. Sliding slowly down her face, the wax beneath her skin was making it blotchy, red and puffy in parts. As early as 1909, when she turned up at the Berenson villa I Tatti, Mary Berenson found her ‘impossible in manner & conversation’ and ‘gone off terribly in looks’. But nothing seemed to deter the men who pursued her — or her own determination to hold them off.

Her goal became a step nearer when there was a legal separation between the Marlboroughs in 1907. The marriage had been doomed from the start: Consuelo forced into it at 18 by her ambitious mother, Marlborough, deep in debt, needing Consuelo’s $2 million dowry; and both in love with others at the time.

By 1912, when she was 31, Gladys had almost openly become the Duke of Marlborough’s mistress. When the Marlboroughs were finally divorced in 1921 the Duke was free to marry Gladys, now 40.

It should have been a fairy-tale ending but alas, it was not. Gladys, to put it bluntly, was not good wife material — hardly surprising, considering her past life. Rich, brilliant, easily bored, spoilt beyond all measure because of her amazing looks and damaged by tragedy, her later irrational behaviour becomes easier to understand, from exaggerated grief at the death of a spaniel to the pulling out of a revolver at a dinner party and laying it beside her plate (‘I might just shoot Marlborough,’ she told a startled guest).

At another dinner, when the Duke was talking politics, she suddenly shouted at him: ‘Shut up! You know nothing about politics. I’ve slept with every prime minister in Europe and most kings. You are not qualified to speak.’ Both statements might have been true but they did nothing to reintroduce marital harmony.

Eventually, after much in-fighting, the Duke left Blenheim, Gladys was evicted and settlements arranged. Before she could divorce him, the Duke died (in June 1934). From then on, despite searchings-out from friends, Gladys withdrew more and more from the world, first living quietly in the country, her jewels and paintings hidden (they sold for £784,000 after her death), then, as she refused all care, being removed from her lonely, squalid existence and taken to the Northampton hospital where Hugo Vickers found her; here she spent her last 15 years. At the end of the book the reader can only say: ‘Whew! What a story.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in