It’s a sweltering night in Manhattan, circa 1947, and on the doorstep of a brownstone tenement three women are waiting for their menfolk to return. There’s plenty to gossip about. The Hildebrands upstairs are being evicted tomorrow, and the Buchanans are expecting a baby. And what’s the deal with Mrs Maurrant and Steve the milkman? Old Mr Kaplan reads the newspaper and denounces the bourgeoisie. A kid cadges a dime and big, kind Lippo Fiorentino arrives home from work with ice creams for everyone.

At which point it becomes fairly safe to conclude that the America of Kurt Weill’s Street Scene is not the America of his Mahagonny. Forget the acid harmonies and hard-left caricatures of his Berlin collaborations with Bertolt Brecht. There’s something touching about the immigrant Weill’s attempt to cram the whole American melting pot into the first act of his Broadway opera, and the bittersweet, noir-ish yearning that saturates his music even when it swings. Street Scene is busy, confusing and anything but idyllic. One character calls the tenement ‘this sewer’. Yet it’s recognisably the American dream: grimy, careworn, often harsh, but full of hopeful, believable individuals living their lives, one way or another.

Matthew Eberhardt’s new staging for Opera North moves the action in from the doorstep to the central stairwell, a tangle of staircases and landings that gets plenty of use whenever Weill drops the opera bit and goes all out for Broadway (the dance routines are terrific). By heading indoors, Eberhardt risks losing some of the sense of a wider society in that teeming first act — the feeling that the rest of America is just around the block; and that teenage sweethearts Rose and Sam really could rinse off the urban squalor and light out for the territory. But it makes good dramatic sense after the interval when, having spent the first act creating a world, Weill and his author Elmer Rice realise that they still have to give us a story, and zoom in on just four characters while hitting the accelerator on an increasingly melodramatic plot.

Among some 35 named roles — all excellently taken, and most of them just about sustaining their American accents through the long passages of spoken dialogue (Weill rejected recitative on the grounds that US audiences wouldn’t tolerate someone singing ‘Do you want another cup of coffee?’) — Opera North’s casting department got these four spot-on. Robert Hayward, roaring and growling, gives a wounded dignity to the villain of the piece, the brutish husband Frank Maurrant. Alex Banfield’s trim, focused tenor is perfect both for the teenage melancholy of the nebbish Sam Kaplan, and his flare-ups of romantic idealism. It also blends well with Gillene Butterfield’s impassioned singing as Frank’s daughter Rose — who in turn is wholly credible, both physically and vocally, as the daughter of Giselle Allen’s Anna Maurrant: a woman who can see what little love remains in her marriage draining away with the dishwater.

Weill dives deep into Anna’s loneliness, and Allen’s singing showed the same capacity to move from clenched, slightly harsh control to a tarnished radiance — a sound that was beautiful because it was dramatically true. The final tragedy felt like a kick in the gut. Add full-beam choral singing, a whip-smart children’s company and an orchestra under James Holmes that managed to swing on a cent from smoky, silky blues to surging operatic flight, and you could almost overlook all the other storylines that were trailed and then dropped. Does Mrs Jones know about her daughter Mae’s nocturnal shenanigans? Should cuddly Mr Fiorentino really be joking about his wife’s infertility? In 1947, Street Scenesuffered from being seen to fall between genres, neither musical nor opera. But in 2020 it all seems more clear. If Act One resembles the pilot episode of a long-running TV drama, Act Two feels like we’ve cut straight to the season finale. Weill never felt able to work in Hollywood; perhaps it’s a pity that he lived too soon to write for HBO.

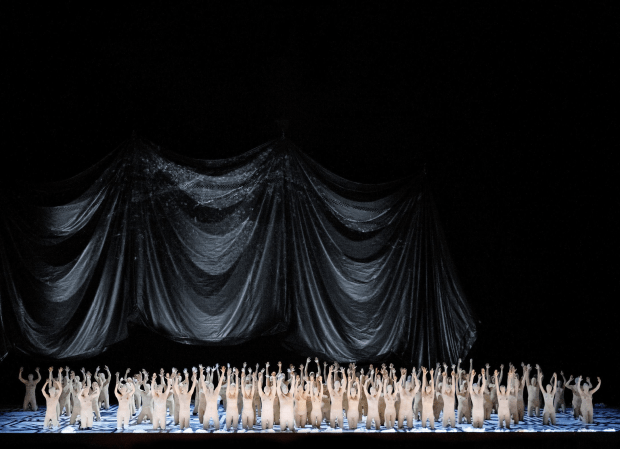

Still, even Beethoven missed the mark occasionally. Sir Simon Rattle and the LSO exhumed his duff oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives, and performed it with a brilliance that gave some decidedly underwhelming music absolutely nowhere to hide. The choruses blazed, the tenor Pavol Breslik (singing the role of Jesus — no pressure there, then) glowed, and the orchestra fizzed along like it was Schubert or Rossini. If only it had been. When you listen to enough second-rate music, you learn how to make allowances. That melody is almost memorable. The vocal writing isn’t clumsy: it’s characterful. This piece isn’t overlong, it’s just a bad performance. But this was an excellent performance, and Christ on the Mount of Olivesisn’t by Hummel, Cherubini or Farrenc. Unfortunately, it’s by Beethoven.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in