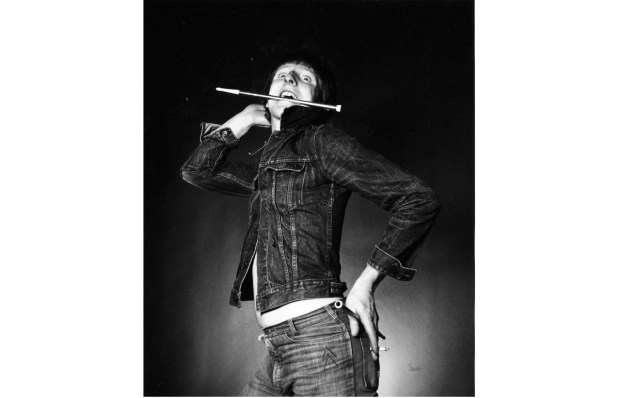

‘The really tricky thing,’ says Clive Anderson as we discuss the topic of being recognised in public, ‘is when they say, “I love your programmes —that thing you did with Margarita Pracatan…” Do I say now that that wasn’t me? Because if you let them carry on about how they loved your Postcards From…, and the Japanese game show, and then you tell them, they get very indignant and say, “Well, why did you let me give you all that praise?”’ It’s easy to understand the mistake in the abstract — indeed The Spectator’s arts editor made it himself in his email to me: ‘Could you interview Clive James for us?’ (If I could manage that, Igor, I wouldn’t be writing for a living.) But to get it wrong with the man himself in front of you? Anderson isn’t even sure that James’s death will solve the problem. ‘No doubt now I’ll have people coming up and saying, “I thought you’d died?”’

The Loose Ends host is preparing for a tour of his one-man show Me, Macbeth and I. It’s a mix of stand-up, theatrical anecdote and personal reminiscence (‘two thirds of the title is me, after all’). Central to the structure is Anderson’s fascination with what he calls ‘the greatest play ever written’. This dates from his schooldays, when he was denied a prominent role. Though perhaps, given the play’s reputation, that was a fortunate escape. ‘The bad luck thing dates from the first-ever performance,’ he explains. ‘The boy playing Lady Macbeth died. Also there was the witchcraft element. Shakespeare had included that to appeal to James I, who was interested in all things spooky — in fact, he’d written a book about the subject. But the rumour got around that Shakespeare had included real witches’ words, thereby unleashing all sorts of evil forces.’

Three centuries later Orson Welles decided to double down. ‘He did an all-black performance, and replaced the witches with a real witch doctor — if that’s a term we accept — who played out curses on his drums. The production got a really bad review from the premier New York critic of the day. The witch doctor took against this, and put a curse on the critic. Two days later the critic died.’

The young Anderson’s yearning to perform continued at university (Cambridge Footlights), then in his legal career (‘I wanted to be a barrister appearing in court, rather than a meticulous lawyer poring over contracts’), and then in his early attempts at stand-up. ‘I did the first night of the Comedy Store when it opened in 1979. Then it moved from its funny little strip club in Meard Street to somewhere in Leicester Square, and I was on the first night there too. Then for “safety reasons” it moved from the ground floor to the basement — I had no idea how that made it more safe — and I was on that first night as well. But then, typical of my approach to career development, I didn’t do the first night when it moved to its best, most established premises.’

Nice self-deprecation: the reason Anderson didn’t do it is that by then he was re-inventing the TV chat show. Out with Parky allowing David Niven his 20-minute monologues, in with Clive Anderson Talks Back. The clue was in the title. ‘There’s no beginning to your talents,’ the host told Jeffrey Archer. ‘The old jokes are the best,’ replied the author. ‘Yes, I’ve read your books,’ countered Anderson. The recording was so bad-tempered that Archer tried to stop it being broadcast. ‘He threatened to sue us if we put it out. But I think he used to do that quite a lot. He sticks by his version of events in everything. I genuinely think he thinks you’re a bit mad if you raise questions about his version, because by now he’s convinced himself of it.’

Which is why Anderson’s approach was the best way to confront him. But was that true of the Bee Gees, who famously walked out of their 1997 interview? My memory of the event has always been that Anderson had it coming, his sarcastic one-liners unworthy of a chat with an unoffensive trio who, unlike Archer, didn’t need bringing down to size. But rewatching it, I found the reality more nuanced. There’s way more of Anderson saying how much he likes their music (‘that was true, I was of an age [he was born in 1952] where their early stuff was memorable’), many more polite, straightforward questions. It’s just that every now and then he can’t resist a gag. The one at which Barry Gibb’s face first darkens is Anderson calling them ‘hit writers’, then asking if there’s a letter missing off the front.

‘That’s a bad line,’ says Anderson. Does he regret it now? ‘Yes, it was poor. But it was only meant as a joke. I’ve always been like that in conversation — I like to come out with a gag. I know it can be annoying.’ Certainly you could see him as open to the charge of ‘no one likes a smartarse’. Do friends or family ever tell him to rein it in? He smiles. ‘That, er, may have been said. I know a lot of people who are the same as me, and when you’re rat-tatting with them everyone enjoys it. But I forget that it’s not always entertaining to everybody else. That’s probably the mistake I was making with the Bee Gees.’ You get the impression Anderson regrets the incident not just because it was a professional failing — an inability to keep his interviewees in their chairs — but also a personal one, an offence against the common rules of civility and respect.

It’s a sign of how media-literate we all are these days that he can make an interesting few minutes of his stage show out of the ‘behind the scenes’ story of the interview’s implosion. How, for instance, the Bee Gees were ‘extra’ guests tacked on at the end of another recording. ‘That meant the audience and I were already in a very “up” mood, we’d already got to whatever fever pitch you can create in a TV studio.’ Parky was traditional, Clive Anderson was post-modern, Clive Anderson’s explanation of Clive Anderson is post-post-modern.

But then popular entertainment has always had its quirks. The ‘being recognised’ conversation tips off a memory about Anderson’s friend Griff Rhys Jones. ‘People didn’t always recognise him. Everyone, the whole world and his wife, used to recognise Mel [Smith], often at Griff’s expense. One day Griff was being driven to a recording. There’d been a mix-up with the cars, and Mel had been left standing on the street. Griff saw him, so he wound down the window and yelled “MEL!” But instead of stopping, the driver sped up, saying, “Nah, famous people don’t like it when you do that.”’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Clive Anderson’s Me, Macbeth and I is on tour from 13 March to 24 May.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in