From the moment when Boris Johnson announced that the country was moving from containment to ‘delay’ in handling coronavirus, the world’s biggest healthcare organisation has been on a war footing. What doctors like me have witnessed over the past days and weeks has been nothing short of extraordinary. Trusts in the NHS declared a ‘major incident’ on the evening of the announcement, and emergency plans swung into action within hours. By the time I came into work the next morning, managers, who had been up all night, had already started to implement profound changes to the way in which the hospital and services were run, and this continued over the following days. It was replicated in every hospital across the country. We’re braced, now, for whatever might hit us.

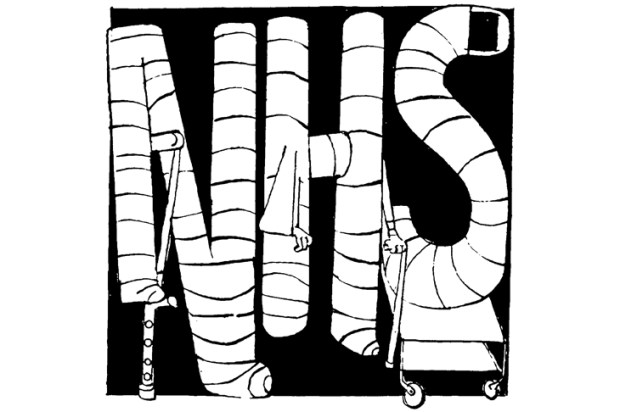

I have my criticisms of the NHS but its behaviour now is a wonder to behold. Decisions that used to take months or even years because of endless pointless form-filling and meetings are now made in less time than it takes to boil a kettle. We have also had to wind down anything not judged to be critical. For example, I work in mental health. Patients on waiting lists for psychological treatment, many of them very unwell, are being informed that everything has been cancelled indefinitely. This has been heartbreaking, especially as many patients had waited months to start therapy. I don’t know how they will cope and worry that many will deteriorate. I fear that some will die.

Entire wards have been discharged in preparation for Covid-19 patients. Services have been reconfigured and reorganised, involving difficult and often uncomfortable decisions about having to redeploy staff and clear space. All in preparation for the tidal wave of seriously sick patients that is anticipated. In a matter of days, designated Covid-19-positive wards had been set up, with staff trained, and they had become fully operational. Red tape is now nonexistent. It’s nothing short of extraordinary.

GP practices have been divided into ‘hot’ ones dealing with suspected Covid-19 cases and ‘cold’ that are dealing with every-thing else. Services and NHS trusts across London, where I work, are pulling together to pool resources. Junior doctors are being reassigned to acute care. A consultant surgeon friend of mine has told me how all her junior doctors are now assigned to help treat Covid-19 patients. She has had her usual operating lists cancelled so she can work in A&E, treating non-Covid trauma emergencies as they come in. Any spare bed is being freed up and every possible space, such as day hospitals or clinics, are being redesigned to be suitable for treating Covid-19 patients. The speed at which this has happened has been mindblowing.

An NHS infamous for its bureaucracy is now behaving like a Silicon Valley startup: if you can show that it will help patients and get the service ready, then it’s green-lit. Just get on with it. Many of us have noted that this is how it should have been in the health service all along — but somewhere along the line the apparatchiks took over and stifled innovation. Not any longer. It’s been fascinating to watch staff rise to the occasion, natural leaders taking charge in place of those we can now see were just paper-pushers. It’s also become apparent how so many of the managerial jobs are unnecessary or redundant now that the chips are really down. Perhaps this will create a culture shift in the health service that makes it more focused on outcomes and patients’ care and less interested in the labyrinthine and suffocating administration.

The NHS is reliant on many external factors in order to survive this contagion. We hear much about the lessons from Asia being to ‘increase testing’ but this is more complicated than simply ordering more tests. False-negative results are an issue with the Covid tests: it’s estimated that up to a quarter of those with the virus will be told they don’t have it. So until we have a better test, the advice must stay the same — if you have symptoms, you have to self-isolate.

This is having devastating consequences for the NHS workforce. Anyone with even the slightest symptoms has to go off for seven days; anyone living with someone with symptoms has to stay off for two weeks. In my NHS trust, there are 184 doctors. As I write, more than 40 are at home isolating — or off sick. If these figures continue to multiply, this alone could bring the health service to its knees. Yet we are powerless to do anything about it until testing improves.

We also need tests that can show if someone has had the virus and is therefore probably immune. We’re told that this test is coming: once we have it, we can start deploying immune staff members to the front line safely, without worrying about sending them into harm’s way. At the moment we are sending doctors, nurses and other clinical staff into a potentially deadly working environment — and they know it.

We’d been told that the government had actually stockpiled PPE (protective equipment to prevent infection) but that when they came to check, it had expired several years ago. It seems that no one ever really thought it would be needed. There is now a mad scramble to get adequate protection for workers on the front line. This is not the fault of the NHS — but if doctors and nurses start dying, it will be the NHS that crumbles.

At times of national crisis, we see the potential value of having a national healthcare system like ours. There is no way that other countries could have achieved that kind of extraordinary, gargantuan reorganisation in literally a matter of days. We all knew that there would be changes to the services we offer, but the scale and speed of these changes has taken us all by surprise. It has been breathtaking to witness. A friend who works in intensive care called me a few days ago: ‘We’ve created an entirely new intensive care unit, from scratch, on a ward.’ This kind of thing would normally take months — if not years — of planning. They did it in 48 hours.

This crisis has so far shown the NHS at its absolute best. It’s not just the nurses and doctors. The porters, the mail-room people, the physiotherapists, the radiographers, the receptionists, the estates and facilities people. You quickly learn to appreciate how important each and every person’s job is. I have rarely felt so much in love with a group of people as I have for the cleaners this week. They have been so neglected for so long — subcontracted, undermined and undervalued — yet their work is now at the absolute forefront of fighting this damned virus. A GP friend found one of the cleaners in the toilet crying because she was so scared of catching the virus and passing it on to her elderly father, whom she lives with; but still she came to work every day. Will the NHS be able to maintain this level of dedication from its staff? Only time will tell.

I am still scared though. Part of the purpose of the changes is to free up staff. I assumed this was simply in preparation for them to care for sick people with corona-virus and was puzzled when they were all sent home to work, to call patients and video-conference with them instead. Why not just keep them at work so they could keep seeing patients in person until the corona-virus patients started to arrive? Then a manager explained that they were being isolated so that they could be drafted in when we all — inevitably — went off sick. They were the reserves to step into our shoes when we fell to the virus.

I looked around the room of doctors and nurses and I admit I felt sick to the pit of my stomach. One of the things about medicine is that no matter how out of your depth you feel, there is always someone, somewhere, who has seen it before and knows what to do. No one has seen this before. What has been so disconcerting is that the usually sanguine senior staff are clearly just as worried as we are.

At one of the meetings, when we were discussing and planning the changes that needed to happen across the service and the trust as a whole, I looked across at one of my colleagues for some reassurance. I realised with horror she was looking at me for the same thing. The staff are scared of catching it, but are also fearful about the extraordinary changes to the NHS that mean we are simply unable to provide care to patients whom previously we would have considered an absolute priority. The reality of the virus means that while the public are talking about measures like isolation lasting for a few weeks, this will go on for months, maybe even longer. The peak is not expected until May or June at the earliest.

I’m worried about the toll it will take on the patients with mental health problems, who are isolated at the best of times and will inevitably suffer. Patients from all areas of medicine will undoubtedly die, not from the virus but because they can’t get the treatment they otherwise would receive. People who have strokes or heart attacks, for example. Operations are being cancelled for patients, and this will inevitably lead to increased mortality in the coming months. This breaks my heart. Will the public tolerate diminished and inferior care from the NHS while we fight this virus? Maybe for a few weeks, even a few months. But the models suggest this will go on for at least 18 months.

It’s been a tough two weeks and the crisis has hardly even begun. There are meetings every day, seven days a week, among the seniors in the trusts and government and NHS officials. Information is then cascaded down to all of us on the ground to implement changes. Things are still rapidly evolving, changing each day. We are now sitting in eerily quiet offices and wards, waiting. The calm before the storm.

I don’t know what’s going to happen. I have no idea if our efforts will be enough: none of us do. I don’t know if the NHS will be strong enough to weather the tsunami. But take a deep breath: it’s coming.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

spectator.co.uk/podcast - Dr Max Pemberton and Dr Kieran Mullan, MP for Crewe and Nantwich, discuss the NHS’s upcoming battle.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in