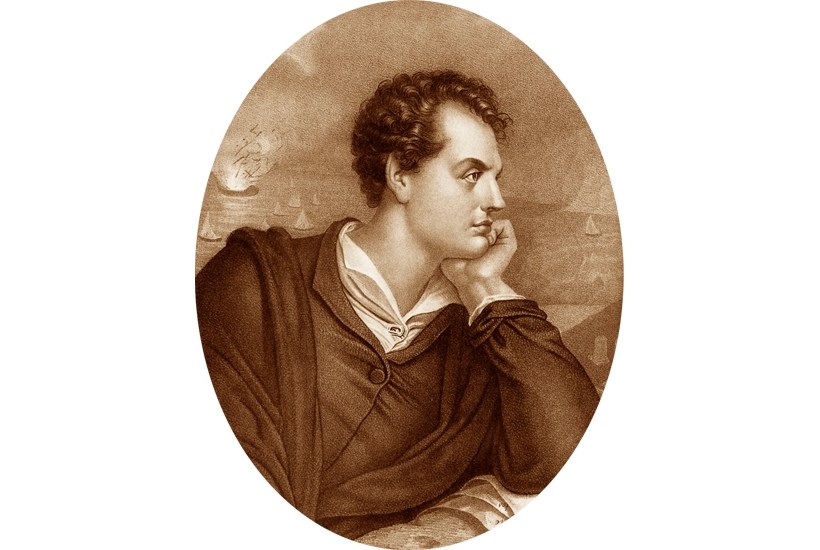

‘Some curse hangs over me and mine,’ wrote Lord Byron, and thanks to Emily Brand, who is a genealogist, it is now possible to see why Byron was so darned Byronic: excess, incest and marital misery flowed in the bloodstream. The gloom that looked like a Regency pose was entirely pre-programmed; George Gordon Byron’s script was handed to him at birth. Being mad, bad and dangerous to know was as instinctive to the Byrons as howling at the moon for a pack of wolves.

When he compared his family to ‘whole woods of withered pines’, the poet was not exaggerating. Every branch was rotten. The son of a sociopath known as Mad Jack and the grandson of an ill-fated mariner dubbed Foul-Weather Jack, the ten-year old boy inherited the title from his great uncle, the 5th Lord Byron, who was generally referred to as the Wicked Lord or Devil Byron. The barony came to little George Gordon after the premature deaths of a heap of cousins he had neither heard of nor met: in order to claim his coronet, the pudgy, club-footed lad from Aberdeen had climbed over more dead bodies than Richard III.

Brand frames this gloriously entertaining portrait of Byron’s 18th-century forebears around Newstead Abbey, the family seat since 1540. Built by Henry II to atone for the murder of Thomas Becket, the priory was raided by the King’s men during the dissolution of the monasteries and then looted by the Parliamentarians during the civil war, after which it was ransacked again by the Wicked Lord in order to pay his debts.

For the Romantic poet, who took up residence in 1808, Newstead was not a home but a reminder of his family’s fate; it was also a thrillingly real-life example of the Castle of Otranto or any of the other medieval monstrosities that kept Jane Austen’s Catherine Morland awake at night. Gothicism was à la mode.The Wicked Lord, who dined with a pair of loaded pistols at the table, trained ‘racing’ crickets; after his death, the crickets left the Abbey in a great black cloud. Accordingly, the new Lord Byron drank wine from a skull while his guests danced around dressed as monks.

The fall of the house of Byron began in 1720 when the 55-year-old William, the 4th Lord (dull enough not to be given a nickname), married Frances, the teenaged daughter of Lord Berkley. A man of taste, he turned Newstead into a palace of sensibility, and here he raised his five children, the eldest of whom, William and John, are the lead males in what follows.

Sweeping away the past, the 4th Lord replaced the Abbey’s dark panelling with light, painted wood, swathed arched windows in yellow silk and converted high-ceilinged halls into suites of apartments. The refurbishment, says Brand, was his lordship’s ‘masterpiece’, which is doubtless why his wife hated it and his heir destroyed it as soon as he got the chance.

When the Wicked Lord inherited Newstead in 1743 he returned it to its former decay, building a creepy gun tower and a stone battery with crenellations and parapets. Lazy, cowardly and incompetent, he was described by Gertrude Savile as having a ‘sad caricter in everything’, and by Horace Walpole as ‘an obscure lord’ and a ‘worthless man’. Having stalked and abducted an Irish actress called George Anne Bellamy, he ran a sword through the stomach of his neighbour, the much loved William Chaworth, over a row about estate boundaries. After incarceration in the Tower of London, he was found guilty of manslaughter and given a small fine.

By now he had dismantled his wife’s considerable estates and spent his way through her fortune, buying whatever he felt like: Titians, Raphaels, Holbeins and a model navy for his lakes. It’s hard to imagine what this navy must have looked like, but it appears to have been life-size. Twenty-five-ton ships were pulled up to Newstead by armies of horses, and a sailor and his boy were hired to maintain and crew the vessels. No Byron marriage lasted for long, and after parting from his wife the Wicked Lord made ends meet by pawning Newstead’s brass locks and floorboards.

While William was playing at being admiral of his own fleet, his brother John — ‘Foul-Weather Jack’ — was having his own adventures at sea. Comically unfortunate, each of John’s voyages was cursed by an albatross. Aged 17, he survived a shipwreck and a mutiny, living for months on an island rock where the murderous crew ate his dog Boxer and then ate the vultures who were pecking at the corpses. John’s sufferings were recounted in The Narrative of the Honourable John Byron, one of the greatest sea stories of the age; and in Don Juan,the poet later described his hero’s shipwreck as ‘comparative’ to the one ‘related in my grand-dad’s Narrative’. Foul-Weather Jack, irresistible to women, was as much a role model for his grandson as the Wicked Lord. ‘He had no rest at sea,’ Byron said of his grandfather, ‘nor I on shore.’ But Foul-Weather Jack had no rest on shore either, where he found it impossible to settle into married life and amassed his own vast debts.

Sophia Trevanion, John’s long-suffering wife, was a friend of Hester Thrale and Dr Johnson; but more importantly she was the mother of Mad Jack, the moustache-twirling villain of the next generation. Aged 22, Mad Jack eloped with Amelia Osborne, the wife of the Marquis of Carmarthen, who gave him a daughter and then died. Having squandered his first wife’s fortune, the widower quickly married a Scottish heiress called Catherine Gordon, by whom he sired a son. After running through her inheritance too, Mad Jack disappeared to France, where he died in 1791. Catherine Gordon doted on her husband’s memory, but Mad Jack’s passion was reserved for his sister Fanny, to whom he wrote letters about his sexual prowess, while reminding her to not make herself ‘too handsome, as I am too mad already that you are my sister’. His two children meanwhile, Augusta and George Gordon, inherited their father’s incestuous longings and produced a child of their own.

This is not an easy history to follow. The men are called either William or John and the women are usually Fanny or Frances; dozens of children with the same names are born and then die, and Brand runs several stories simultaneously while moving back and forth through time. The effect of her narrative elasticity is to give the book a novelistic depth, which is added to by rich topographical descriptions and a packed historical backdrop. The Byrons, she concludes, were less cursed than the product of an age of upheaval. What with Jacobite threats, mad kings and the French Revolution, they had ‘weathered some of the most turbulent moments in British history’. They were all, in other words, a Foul-Weather family.

‘Newstead and I stand or fall together,’ George Gordon announced to his mother in 1808. ‘I have now lived on the spot, I have fixed my heart upon it, and no pressure, present or future, shall induce me to barter the last vestige of our inheritance.’ By 1816, however, he had fled to the continent, pursued by rumours of incest and marital cruelty, and in 1817 he sold the Abbey to pay off his debts. It was not for nothing that the family motto was Crede Byron.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in