The Beeb has released Simon Godwin’s Hamlet staged by the RSC in 2016. The director makes one major change and leaves it at that. Elsinore is transposed to a present-day African republic where members of the ruling clan are jockeying for power after the dictator’s death. This chimes with our understanding of geopolitics and lends simplicity and coherence to everything else. African flavours dominate the costumes, the furnishings and the music. The casting makes sense too. Most of the company are black and the characters are played by actors of the right sex. It’s rare to see Shakespeare’s gender choices followed faithfully.

The superstitious element is strongly emphasised. The Ghost’s second appearance on the battlements (often omitted) is included here as he commands Hamlet, Marcellus and Horatio to swear an oath of silence. The characters cut their palms and share their blood in a gruesome rite of fraternity.

Cyril Nri plays Polonius for comedy as a chuntering buffoon rather than as a serious power broker. He even gets a laugh from his death when the banner behind which he’s hiding collapses on him like a paint spillage. Natalie Simpson adds a welcome layer of spikiness to Ophelia’s habitual air of wounded confusion. Marcus Griffiths is a fine Laertes with a commando’s swagger. When his rebels storm the palace, he drops in from a rope, SAS-style.

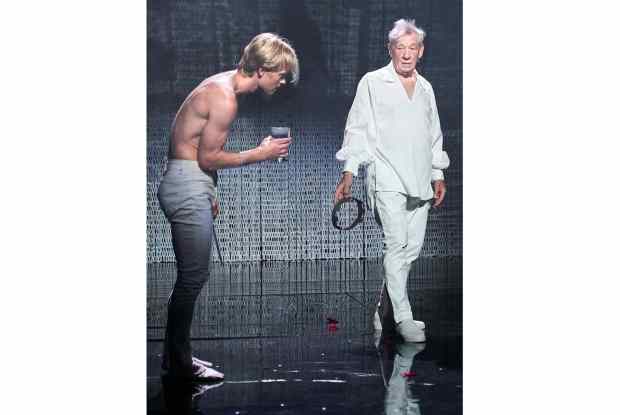

Paapa Essiedu is a dazzling, all-encompassing prince. Sulking furiously in Act One he spits out his words at Claudius. When he feigns madness, he wears a paint-spattered blazer like an artist taking a break from frenzied experiments in the studio. He can switch his mood instantly, without effort or calculation, from tragic loneliness, to bitter anger, to larky chitchat, to savage wit. At times he turns off the performance entirely and stands on stage, a plain, unhappy man, with nothing to keep him going but his stillness and his mysterious, charming energy. A great Hamlet. One slight quibble. He and Laertes prepare for their duel by stripping to the waist and donning tight dark boots and pink pantaloons. That’s not the right moment to go full Ibiza.

Another RSC piece, I, Cinna (The Poet), is a metatextual response to the lynching of Cinna in Julius Caesar. Jude Owusu has a winning, dreamy presence in Tim Crouch’s 48-minute play. And his Cinna is instantly recognisable: the kind of subsidised poet who wins prizes, appears on Radio 4 and bores children to death.

‘I want to write about love and freedom and peace,’ he moans, ‘but this world won’t let me.’ His descriptions of ancient Rome contain bizarre references to lamp-posts, gold taps and tanks on the streets. He inaccurately characterises Caesar as a Trump-like figure. ‘He’s so rich. He bought his way to the crown.’ In fact Caesar lacked personal wealth and relied on conquest and fame to propel him to power. Hence his wars in Gaul and Britain. When Mark Antony whips up the crowd after Caesar’s death, his fiery speech is relayed to Cinna on TV. ‘Poetry has done its job,’ he comments, ‘words have defeated actions.’ He seems unaware that Mark Antony’s eulogy is about to spark a riot that will lead to a civil war.

The monologue is conceived as a piece of schoolwork and Cinna gives instructions about creative writing exercises. ‘This is your poem. Write my death,’ he says, vaguely. Throughout, he mixes lines from Shakespeare with his own trivialities. ‘First you must live. Then you must question. Then you must be free.’ A newcomer might assume that Shakespeare wrote that and forgot to cross it out. The RSC should have thought twice before turning this sub-par effort into a film.

Everyone is looking for new ways to present the classics during lockdown. Auckland Theatre Company has attempted to produce Chekhov’s The Seagull via Zoom. It hardly seems credible that such an emotionally tangled play could be done by actors who never physically meet. Here’s the solution. We’re told that the characters normally share a summer holiday by the lake but the pandemic has scattered them. So they come together online to watch Konstantin’s new play being livestreamed. His mother Irina and her lover, Trigorin, are an A-list Hollywood couple. Konstantin’s play becomes a dream sequence filmed by Nina with a Gothic voice-over, much like Chekhov’s original. The characters watch the broadcast in polite silence. But jealous Irina deliberately fails to mute her microphone and makes audible comments throughout. At the climax, she turns to a piano and adds melodramatic chords to satirise Konstantin’s pretentious script. ‘What are you doing?’ he screams. ‘Collaborating,’ she says, innocently.

The production finds similar solutions to the play’s numerous challenges. Some of these ideas add new layers to the characters. Trigorin, for example, accidentally films himself with his helicopter in the background. More top-quality Chekhov like this is needed.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in