The enforced boredom of lockdown has been replaced by a feeling of loss. My nephew by marriage, Hansie Schoenburg, died aged 33 from a brain tumour, and then there was the death of my close friend Shahriar Bakhtiar, aged 72.

Hansie was tall, blond, a Yale grad, and extremely handsome. Recently married, he died surrounded by his family. He was very close to both my children. Shahriar was the Persian Boy who, as a slender, bright-eyed six-year-old with not a word of English, was dispatched from Persia to an English school known for its cold rooms and strict rules. The Persian Boy learned early to do without parents.

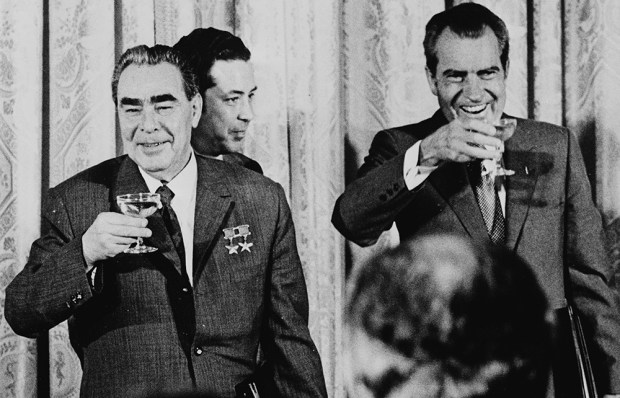

The bitter irony of their respective deaths was that while Hansie had been willing himself to live these past 15 years, Shahriar had had enough. Unlike many vulgar, newly rich Iranians who ran around London’s clubs back in the 1970s, Shahriar Bakhtiar came from an old and good family that had seen better days when the last Shah’s father grabbed power in the 1920s. A young Shahriar was first noticed by the last Shah’s twin sister, Ashraf, in Tehran, as was a young Taki in the south of France. The Persian and I did not know each other but we sort of got together when the predatory Ashraf invited me to dinner. I did a Usain Bolt and ran for the hills; Shahriar obeyed the royal command.

I never allowed him to forget it, that’s for sure. The truth is that 60 years ago I was sneaking around with Soraya, the Shah’s beautiful ex-wife who was divorced by him because she could not have children. Soraya warned me to keep things to myself, otherwise the Shah’s secret police would do me in. (He was very jealous.) The Persian Boy, in the meantime, did not stay long with the emperor’s twin. He loved beautiful, tall English girls, and he and I got our stories straight. It was the beginning of a beautiful friendship, pardon the pun.

What followed was what I can best describe as a period of extended adolescence. The Persian cut a wide swath through English debs — Trinnys and India-Janes galore — because back then he was loaded, slim, short and very handsome. He had taken to England like the proverbial duck to water; an England dominated by public school values, such as fair play on the sporting field. I have met many athletes, but no one as naturally gifted as this prime candidate for having sand kicked in his face by the beach bully. Not a grain of sand ever touched him. He was a terrific all-rounder in cricket and a very good tennis player. I played against him when I could still hit the ball and he was tough, never giving pace and returning everything. He was also known as the man who never slept.

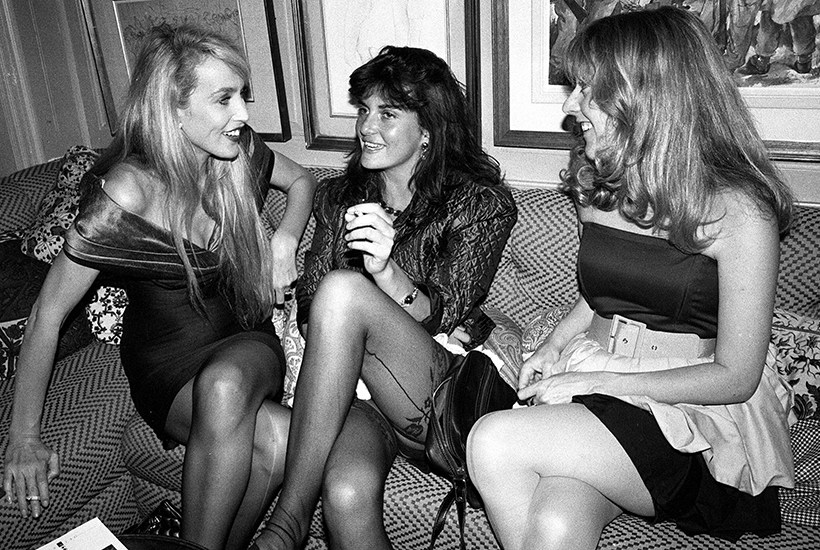

Always in love, he brought to mind Cyril Connolly’s Enemies of Promise and the dread symbol of the pram in the hall. The Persian Boy became a fixture in the chic nightclubs of the time, Annabel’s and Tramp, always escorting stunning young women, always on the lookout for more. He would be the last to leave but up early for tennis or cricket practice. His afternoons were spent playing bridge or teaching the game, his weekends in grand country houses captaining cricket teams, never out, taking wicket after wicket.

As the years went by, Shahriar’s income shrank and he was forced to downsize. Zac and Ben Goldsmith came to the rescue. He became a member of the family, and returned the favour with more love for the Goldsmiths than he had even for his own brood, of whom he never spoke. When Ben’s lovely young daughter died in a freak accident, I rang the Persian in order not to bother the grieving Ben. Shahriar was in a terrible state and crying over the telephone.

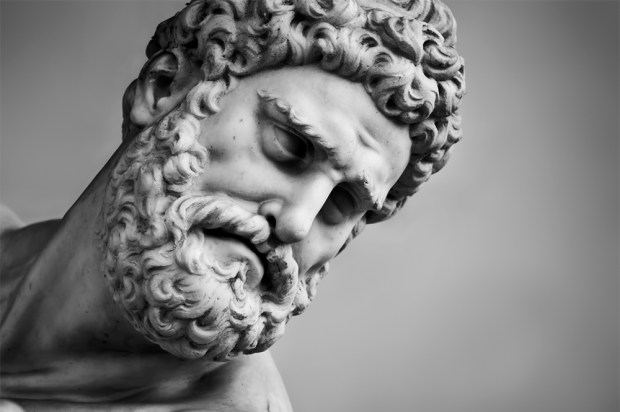

I suppose childhood distress does not necessarily ennoble or strengthen a person later on in life, but in the Persian’s case I think it did. He never complained about reduced circumstances and continued his self-destructive ways until the end. (I admired that.) But licensed hedonism takes its toll. Still, even over 70 he captained Goldsmith’s cricket team and was the best player among 20- and 30-year-olds. As the world became brasher, his own became untenable. Ben Goldsmith aside, his closest friends were the families of Tim Hanbury and Harry Beaufort. Tim, Harry, Shahriar and I would always take the main round table at San Lorenzo and invariably I would begin a long soliloquy aimed at the females on our table about how we Greeks had made mincemeat of the barbaric Persians and had even gone over there and taught them some manners under Alexander the Great. It was a ritual that may have bored Timmy and Bunter but not the Persian Boy. He would look at our girls between puffs of his ever-present roach, flash a wintry smile, roll his eyes upwards, and they would invariably take his side against the Greek bully. He made up for the lost wars by beating the poor little Greek boy to the punch 2,000 years later.

His worldliness was marked by courtesy and sweetness, but there was always the sense that his life might end sadly. Hansie’s life was Schubert’s Nocturne; Shahriar’s was a Cole Porter tune.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in