Nicholas Hytner’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream opens in a world of puritanical austerity. The cast wear sombre black costumes and Oliver Chris, with menacing swagger, brings a note of palpable sadism to the role of Theseus. Then things relax as the ‘mechanicals’ in modern boiler suits prepare to rehearse the play. Hammed Animashaun (Bottom) dominates this little scene with his impish charm and unpredictability. He’s a high-calibre talent of whom more will be heard.

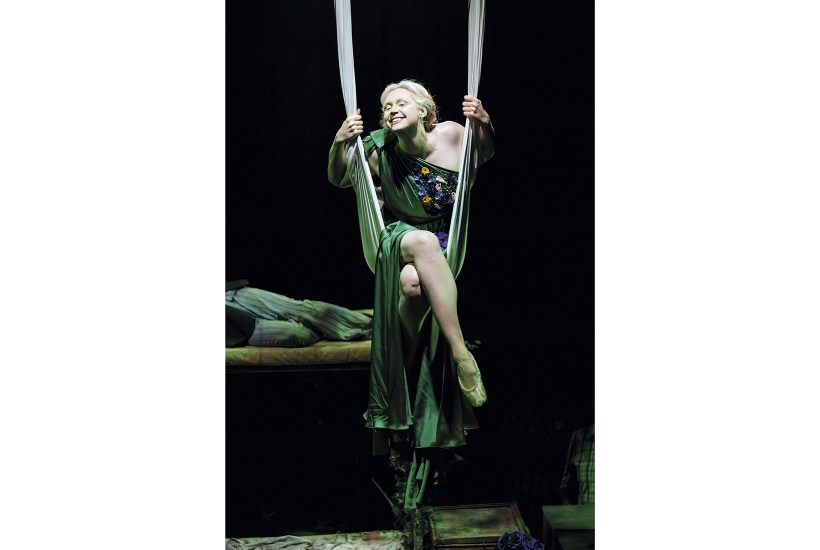

After this solid opening, disaster strikes. The forest sequences, already devilishly overcomplicated, are presented on double beds which move restlessly all over the shop and make the story almost impossible to follow. And Hytner has flipped the chief roles. In this version it’s Oberon, not Titania, who falls in love with Bottom dressed as a donkey. Is that a blow for feminism? If so it has strange results. Gwendoline Christie (Titania) has lost the chance to play an iconic piece of Shakespearean comedy. Act One culminates in a spoof dance routine between Bottom and Oberon choreographed by Arlene Phillips. What a triumph this might have been if the actors had been left alone on a normal stage. But they’re stuck on the mattresses of the wandering double beds and they have to compete with a handful of twirling acrobats who dangle from silk ropes and perform somersaults. Far too much fussy detail. The accompanying nightclub soundtrack turns the scene into a chaotic, if good-natured, muddle. Is this Shakespeare? It looks like a fancy-dress party in a warehouse.

The Finborough Theatre offers two plays of Edwardian vintage. It Is Easy To Be Dead is a biography of the Scots poet Charles Hamilton Sorley, who was killed in action in October 1915. Before the war he studied at Oxford and at the University of Jena where he fell in love with his married landlady. Unable to express his feelings physically, he declared himself a German patriot. The show features excerpts from Sorley’s oeuvre, including a sonnet, ‘The Army of Death’, which shows unmistakeable flashes of greatness.

Jane Clegg is a family drama with reforming overtones written by St John Ervine. Jane is an unhappily married mother of two who inherits £700 from an uncle. But she refuses to share it with her husband, Henry, who works as a lowly bank clerk and gambles heavily. ‘He couldn’t run a business,’ she says bluntly. Her son’s education would be a wiser investment. Jane is frustrated by the life of drudgery that she shares with her elderly, prattling mother. ‘It’s awful that I shall sit here always, mending things, and waiting for Henry to come home.’

Henry shows up for supper and brings with him a sly, insistent bookie who demands the repayment of £25. When he learns that Jane has inherited money, he advises Henry: ‘Give her a clout on the side of the head if she gives you any lip.’ But Henry hasn’t the guts to take on his wife and his mother-in-law. So the bookie threatens to reveal that Henry has a pregnant mistress. ‘Funny, isn’t it,’ he wheedles, ‘the one you’re married to ain’t half as nice as the one you keep.’ But Henry takes a different route and tries to solve his problems by embezzling a large sum of cash from the bank.

This overlooked drama is gripping on many levels. The interlocking debts and swindles. The emotional torment of a spurned husband attracted by a racy young girlfriend. The quest for dominance by a dutiful wife newly empowered by money. The characters are skilfully drawn. Jane looks like a timid domestic creature but she shows hidden steel when she takes on her arrogant, deceitful husband. And although Henry is a philandering rotter he’s blessed with the intelligence to realise that Jane’s honesty and caution are ill suited to his free-wheeling nature. ‘I should have married a woman like myself. Or a bit worse.’ Jane’s mother sits by the fireside delivering off-beat snippets of social observation. ‘I don’t believe in all this education for women. It unsettles me.’ And the low-life bookie has unexpected qualities. His manners are polished and he has an air of moral dignity. He likes to wear well-tailored, if rather flashy, three-piece suits.

The costumes in David Gilmore’s production are as good as you’ll see in a BBC period drama. And the low-budget set is equally convincing. This superb show was filmed in a theatre whose stage and auditorium are no larger than a squash court. Highly recommended. The play premièred in 1913 and it contains an eerily prophetic line. The bookie, mentioning a disabled friend, says: ‘A man who’s had his leg cut off can always tell when it’s going to rain. Gets a funny feeling in his thumb.’ The playwright lost a leg in the Great War.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in