Keith Douglas is perhaps the best-known overlooked poet. He died following the D-Day landings in 1944, and his Collected Poems were published in 1951, followed by a Selected Poems in 1964. ‘Now, 20 years after his death,’ wrote Ted Hughes in his slightly puffy introduction to that volume, ‘it is becoming clear that he offers more than just a few poems about the war.’ There was a thorough and clear-sighted biography by Desmond Graham in 1974, followed in turn by further editions: another Collected Poems, prose fragments,

a memoir, and his surprisingly boring letters. Yet Douglas continues to be the kind of poet older writers like to present with a flourish as an insider tip: oh, you must read Keith Douglas.

Perhaps this is because his poems work, at their best, as a surprise. They play games with perspective, time and repetition; they make things look different from how you might expect. ‘Cairo Jag’ describes the desert after a tank battle: ‘The vegetation is of iron/ dead tanks, gun barrels split like celery.’ They don’t behave quite like war poems. His most famous poem, ‘Vergissmeinnicht’, begins three weeks after the battle, when the bodies have decomposed. The great critic Ian Hamilton once observed that the trouble with Douglas is that where we assume war poems should be anti-war, his never really are.

Douglas’s other great critic and supporter was his mother, and she put it this way: ‘He had the faculty of looking on himself from a distance.’ In the best poems, written while he was killing time in military hospitals in Egypt and waiting for D-Day, everything is at a strange and prickly distance. But to say this is, of course, to disagree with Ted Hughes. Is there really more to Douglas than a handful of war poems?

Richard Burton’s good-natured new biography is distinguished by an almost fanatical diligence. We hear of the swimming competition which Douglas won when he was seven. ‘As luck would have it his school English and history exercise books from 1935 to 1937 have survived.’ It is always tempting to look for portents. Douglas’s first poem, written when he was ten, was about Napoleon. A few years later, he stole a gun from the school armoury.

It’s hard to love the early Douglas. At Oxford, he was very much an undergraduate. He wrote pugnacious articles for the student newspaper under increasingly silly pseudonyms and told his girlfriends what to wear. Even Burton, who adores him, gets a little irritated. The poems are hard work (‘death crept/ Like a secret jeweller, and the amethyst/ That I diligently sought, he took and stored’).

Douglas enlisted in the summer of 1940 and spent much of the following year in training. For a while, this was like a continuation of school; he quarrels with the sergeant major. But something changed. On board a ship to the Middle East he writes to a girlfriend: ‘We are beginning to look like heroes already — considerably thinner and pleasantly tanned.’ His war was not obviously heroic. In Cairo, he ran over a civilian. He turned up a few days late to the battle of El Alamein, lost his glasses and trod on a land mine. He was often in hospital.

But this odd, disjointed set of experiences is also characteristic of modern warfare. The best literature of the second world war captures this quality: Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead is mostly about waiting for battle; Randall Jarrell’s poems about bombers tend to be about training, not combat. Douglas served in a tank squadron, and his poems give perfect expression to the strangeness of this machine war fought across the desert.

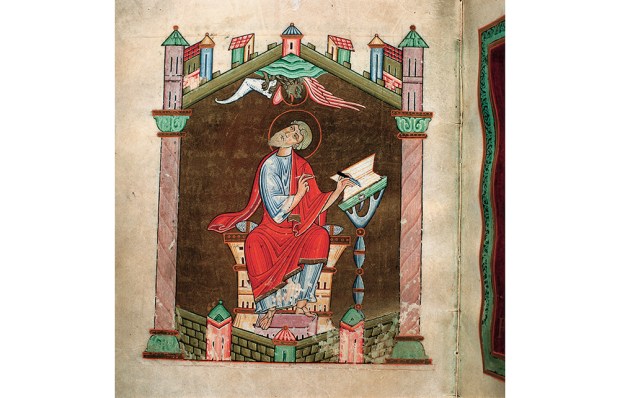

‘Remember me when I am dead,’ begins one of his most well-known poems, ‘and simplify me when I am dead.’ The tone is flat; the game is modernist. Burton’s biography never simplifies Douglas, and this is to its credit, of course, although one might also object that in doing so it goes against Douglas’s own command. But Burton is the kind of biographer who throws everything into the suitcase while resisting any kind of analysis. There is little here on the wider war, or on where Douglas might belong in the changing fashions of poetry. And there is too little on Douglas’s depression (he called it his ‘Bête Noir’), and the strange cartoon-like drawings he often used to illustrate

his writings.

He was shipped back to Britain in late 1943 and as he was waiting for D-Day wrote his final known poem. ‘The next month, then, is a window,’ he speculates: ‘and with a crash I’ll split the glass.’ He was killed in a ditch three days after landing in Normandy.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in