The recent U-turn on masks in schools will likely undermine teaching, not only in schools but also further afield. It will embolden growing calls for university teaching to go fully online when the academic year restarts next month. Jo Grady, general secretary of the University and College Union, is consistently urging the government and university leaders to curb face-to-face teaching on campuses as much as possible. Her demands follow elite universities in the US such as Harvard and Yale which have already committed to online teaching. Many British academics seem to be against reopening campuses over the next few weeks, preferring that universities go fully online while claiming that in-person teaching risks the health of staff.

At the moment, British universities are committed to a so-called ‘blended learning’ model, in which large lectures will be run online, with face-to-face teaching for smaller seminar groups and lab work. While one obvious reason is Covid, another justification is the £9,250 fees every student pays per year. Not unreasonably, colleagues worry that purely virtual learning will lead students to question why they’re handing over vast sums of money. In truth, however, the justification for face-to-face teaching should not be down to cold hard cash. Far more important is the fact that human relationships are crucial to education itself.

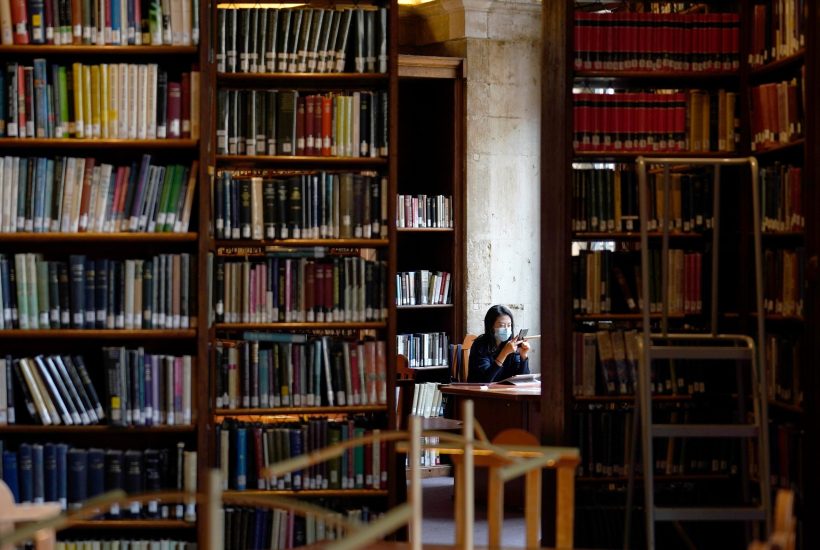

Learning is more than absorbing data, and students are not merely empty vessels. The transmission of knowledge and critical thinking can only occur in the context of social relationships. Education requires socialisation and the cultivation of personal rapport if it is to be successful. And the student-lecturer relationship isn’t the only element of learning. Scholarship requires discussion, engaging one another in a genuine attempt at mutual comprehension. Students need other students as much as they need their lecturers.

Building these relationships is impossible in the creepy two-dimensional world of the Zoom seminar, with students cooped up in their bedrooms while peered at by their lecturers over the internet. Needless to say, universities should not compel any student or member of staff to return to campus if they are particularly vulnerable to Covid-19. Beyond such cases, however, the data suggests that the risk of Covid-19 is mercifully diminishing across the country. In any case, youthful students constitute one of the lowest risk demographics.

Given that so many academics seem inured to the evidence, we must ask why so many seem so quick to avoid their professional commitments to proper, in-person teaching. As with the intransigent leadership of teachers’ unions, so too the academic aversion to teaching paints a grim picture of the professional middle classes in full retreat from wider society.

Ironically many of these same academics who, in other circumstances, would decry the social fragmentation of our heavily privatised, neoliberal society are now complicit in these very same retrograde trends, propagating a new politics of fear. Any critical sociologist worth their salt would be able to explain to students how marginal and oppressed minorities are frequently associated with disease and contamination – or in the jargon of social theory, ‘constructed’ as being dangerous to the rest of society, thereby justifying these groups’ isolation and oppression. With Covid-19, we now risk seeing everyone as a pollutant to everyone else, justifying mutual suspicion, alienation and isolation. Doubtless many critical sociologists have subscribed to this dismal new ideology.

By propagating this notion that campuses are sites of such extreme danger, academics risk undercutting the very justification for university itself (not to mention their own jobs). University leaders and academics must resist this ideology of fear that the government is so quick to spread. We should demonstrate that we are committed to our social bonds in the wake of the pandemic and that our students do not threaten us by their presence on campus. What’s more, it is our professional duty as educators to remind everyone that the most powerful thing about campus life is not the virus, but the possibility of being exposed to new ideas. Keep campus open.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in