Library books often contain more than just words. Tucked away between the pages you might find remnants from previous readers and owners – a post-it note, a bus ticket, a photo or postcard.

One recent discovery found in a Campion College library book was more unusual than most. While researching for an essay on the Russian Red Terror, third-year student Bridget Knight came across a communist bulletin dated Friday, 29 May, 1931, entitled The Abattoirs Blade: To cut deep into the heart of capitalism and expose its rotten inside.

This remarkable document was discovered inside The State and Revolution: Marxist teachings on the state and the task of the proletariat in the Revolution by V.I. Ulianov (Lenin), which was published by the Australian Socialist Party in 1920. Thrilled with this discovery, Bridget brought it to my attention, interested to know more of its history.

The bulletin appeared to have been produced in Sydney by a faction of communists. Curious to find out more about this publication, I contacted the Noel Butlin Archives Centre at ANU. While the Archives Centre holds many trade union records and communist and socialist publications, they didn’t have any copies of the Abattoirs Blade. However, the archivist was able to point me to some newspaper reports which shed more light on the history of this little piece of propaganda.

According to newspaper reports, the Abattoirs Blade appears to have been produced and circulated by Homebush members of the Meat Employees Union. It was blacklisted by the union in 1931. The Sydney Morning Herald reported on 25 June, 1931 that ‘a mass meeting of employees at the abattoirs had unanimously denounced the Communist paper and declared it “black”.’ Unsurprisingly, the Workers Weekly’s report of the event on 19 June that same year was longer and more vivid. It concluded with these emphatic lines: Mr Hutt, immediately after he succeeded in having the ‘Blade’ declared black, can now boast that the Party worker who distributed the ‘Blade’ was arrested and was assured by the Police sergeant that if the ‘Abattoir Blade’ did not come out again no further action would be taken against him. Freddy Hutt, you will have to get more than the police to scare off the Communists, or the ‘Abattoir Blade.’ You will need more support than the whole of the social fascist crew combined can give you to prevent yourself from being sent back into the oblivion from which you came, and from which there will be no return.

Historian and author Professor Stuart Macintyre was able to assist me further in discovering more about this fascinating document. He confirmed the bulletin was an early copy of what became a common form of newsletter. There are very few copies of these newsletters nowadays because they simply were not made to last. A select number would be printed on low-quality paper, to be handed out, read and thrown away. Professor Macintyre also confirmed that the union which produced this bulletin was the Australasian Meat Industry Employees Union, a federal structure with various state branches. He noted that while Communists had more success in Victoria and Queensland, their influence in NSW was limited. Communists working in the meat industry would have had these bulletins produced to hand out to fellow workers, often at the entrance of the meat works.

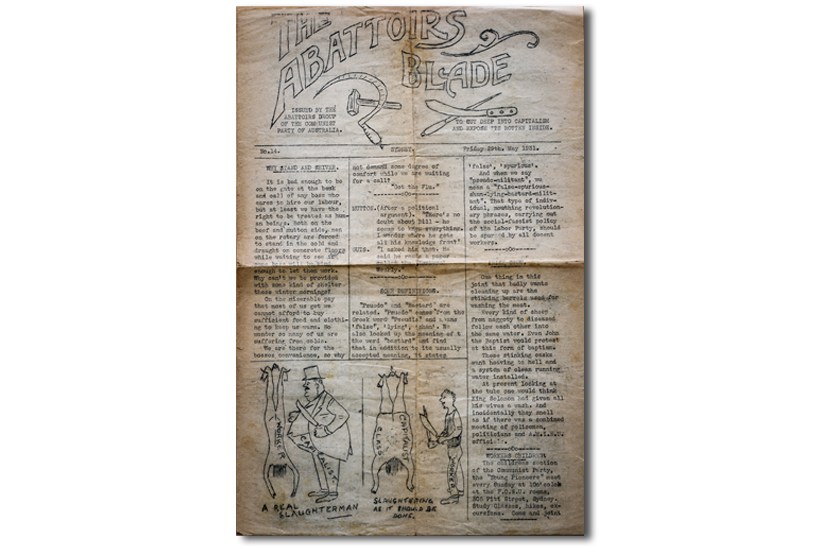

This particular bulletin was produced with a roneograph, a rotary duplicator which presses ink through a stencil. This is obvious in the details of the decorative title and illustration on the front page. The title is printed in large capital letters and underneath the word ABATTOIRS there is a rough illustration of a sickle and hammer. Slightly to the right of this, under BLADE is a sharpening steel and a skinning knife crossed together in a similar fashion.

A crude illustration at the bottom of the front page depicts a corpulent ‘Capitalist’ preparing to butcher a skinny ‘Worker’. It is titled ‘a real slaughterman’ and is contrasted with an adjacent illustration depicting ‘slaughtering as it should be done’ with a worker preparing to butcher a representative of the well-off ‘Capitalist Class’. The content of the bulletin is certainly polemic and even vitriolic at times. Arranged in three columns, the text is divided into short pieces with headings which include ‘Why Stand and Shiver’ and ‘Social Disease’.

The bulletin features complaints about the working conditions at the meat works and the unhygienic ways of washing meat, claiming, ‘every kind of sheep from maggoty to diseased follow each other into the same water. Even John the Baptist would protest at this form of baptism.’ There is also a notice advertising the meetings of the children’s section of the Communist Party, the ‘Young Pioneers’, and a comment on the recruiting campaign which aimed to double party membership and sales of the Workers Weekly.

The bulletin rails against the ‘Labor Weekly’ claiming, ‘this filthy social fascist rag will be shunned by all honest workers.’ It also decries the rationing of work and advocates a minimum wage for both employed and unemployed workers at the abattoirs. It makes very clear the fact that ‘we fight with those who fight for the workers and not with those who fight for the capitalist class.’

Holding this delicate piece of paper and reading the content of the bulletin makes me wonder about those who originally wrote it, held it and read it. What else did the authors write and how far did they go for their cause? What did the recipients think of the contents – were they sympathetic to the Communist party? Did the bulletin become just a convenient bookmark or was its content of significant interest?

I am certainly glad it ended up in this particular book as this ensured its survival. I am unlikely to ever know the answers to my questions, but the bulletin remains a fascinating piece of history and a reminder of the discoveries that can be made within the pages of library books.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Keziah Van Aardt is the librarian at Campion College, Australia’s first tertiary liberal arts institute, based in Sydney.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in