Researching the seditious literature of earlier periods is seldom suspenseful, pulse-quickening work. For every thrill of archival discovery, there are countless hours of slow, methodical, sometimes crushingly unproductive labour aimed at uncovering the individuals and agencies behind books that, as clandestine productions, were primarily designed not to surrender such secrets. The underground networks behind dissident pamphlets in 17th- or 18th-century England, for example, frequently hid their own involvement by withholding the names of authors, printers and places of publication from their title pages, leaving puzzling blanks or laughable fictions in their stead.

While contemporary press licensers had battalions of beagles, book-trade informants and the disciplinary machinery of the state to help ferret such information out, centuries later the hunt is altogether more desk-bound and sedate, the quarry even less communicative: a piece of broken typeface here, an unusual press ornament there, a distinctive watermark in the paper which might — but, more frequently, might not — reveal a pattern of professional behaviour, a person with a name cloaked in an anonymous book.

All of this makes Joseph Hone’s The Paper Chase a remarkable achievement, for he transforms what is essentially a case study of English press censorship following the expiry of the 1695 Licensing Act into a fast-paced, captivating narrative about the attempt to track down the individuals responsible for a pamphlet called The Memorial of the Church of England (1705).

This was an anti-Dissenter work which sought to destabilise the government in the early years of Queen Anne’s reign by arguing that the Church of England was in immediate danger from current tolerationist policies which permitted low-church believers to express only occasional conformity to its ceremonies and doctrines. The queen herself was greatly distressed by the pamphlet’s arguments that she and her ministers were letting established religion go to ruin, and her secretary of state, Robert Harley, set about uncovering and rounding up those responsible for the assertion.

The broad contours of this narrative, and the identity of the individuals implicated in it, will be familiar to those students of 18th-century literature who have read J.A. Downie’s canonical Robert Harley and the Press (1979). But what Hone adds to Downie’s account is a bibliographer’s feel for 18th-century books and manuscripts —his expert knowledge of how books were made and brought into being is worn very lightly — as well as an eye for detail and sense of narrative drive worthy of a fiction writer.

The evocations of London’s thoroughfares, printing houses and taverns are the result of exhaustive research, but they also have the gripping immediacy and plausible detail of an Iain Pears historical novel. Hone studiously avoids offering narrative colour through overstretched ruminations on the winds of change blowing through perukes, or the Enlightenment warming the backs of workers in the printing house (sins of embroidery common to many trade books on more remote historical periods). Rather, archival details drive a meticulous attention to the quotidian effects of geography, weather and working practices on the imagined and recorded lives of the book’s protagonists: the unusualness of the sleet in London in January 1706; the effects of damp on book production; the physical sensations of being pilloried in the stocks; the cries from a debtors’ prison.

That detail can also be hilarious, as in the discussion of the tavern clubs which provided a focal point for political writing of all stripes in the period. (The Devil’s Tavern club on Temple Bar is a key venue for Hone’s analysis of the origins of The Memorial; Addison and Steele’s The Spectator emerged from the Whig Kit-Kat club which convened at other taverns in the vicinity.) Members of such clubs often wrote anonymously or pseudonymously together, again making it difficult for the authorities to punish the perpetrators. So ubiquitous and noisy were they that Ned Ward’s The Secret History of Clubs (1709) fantasised the existence of the ‘Farting Club’, whose members ate cabbage, onion and pease pudding on club nights so ‘that every one’s bum-fiddle might be the better qualify’d to sound forth its emulation’.

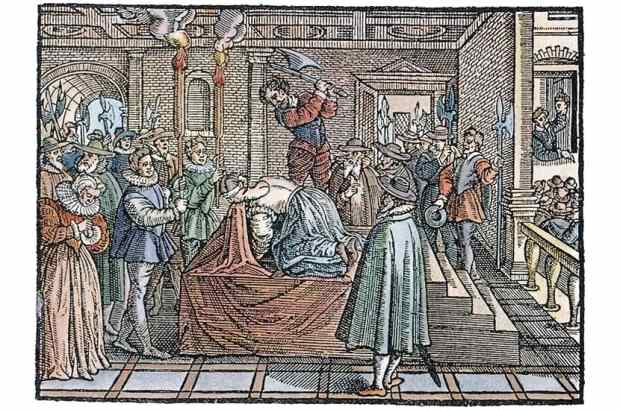

But it is in its focus on humbler individuals who were never invited to brave the doorways of tavern club meetings that Hone’s book excels. The printer of The Memorial was a North Walian called David Edwards who, with his wife Mary, ran a press in Nevill’s Alley off Fetter Lane, near Holborn. Such individuals, without the most meagre Dictionary of National Biography entry between them, typically exist at the peripheries of most accounts of 18th-century press regulation, with more celebrated figures such as Harley taking centre stage. From the moment that an unnamed woman in a velvet mask turns up at Edwards’s premises asking him to print the manuscript of The Memorial in the summer of 1705, Hone focuses the narrative through the experiences of the Edwardses. Whether tracking David’s apprenticeship to the printshop of Thomas Braddyll, re-creating his experience of apprentice riots during the Exclusion Crisis, or later showing Mary desperately knocking on doors to hunt down the author of The Memorial and exonerate her husband, Hone demonstrates how uncovering 18th-century working lives can be every bit as enthralling as tracing the machinations of the greatest politicians of the age.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in