When lockdown was first proposed in March, one of the many arguments against it was that people would tolerate being deprived of their liberty only for a few weeks. The idea of criminalising basic community behaviour — welcoming a guest into your home, educating children, going to church to pray — was viewed as an extreme measure with a short shelf-life. One of the big surprises of the pandemic is to see that lockdowns, in fact, are popular in large quarters. People have complied for far longer than was ever envisaged.

But it’s a careful balance — and examples of overzealous policing risk upsetting that balance. It does not help that the rules change regularly, with even government ministers saying (in private) that they have given up trying to keep track of them. If the confusion spreads to the police, then officers end up targeting people engaged in perfectly lawful activity — as happened to the two women in Derbyshire recently fined £200 each for driving five miles to meet up for a walk.

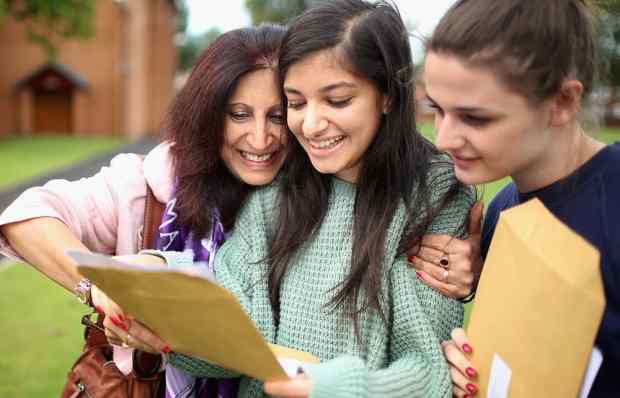

Lockdown has exposed much of the best of human nature, with people willingly making huge sacrifices. A recent study by UCL into public attitudes towards the restrictions shows ‘majority compliance’ with the rules has remained at well over 90 per cent since the beginning of the crisis. It is true that the same study also shows ‘complete compliance’ peaking at just under 70 per cent in April and largely staying between 40 and 50 per cent ever since. But these figures tell a story: the vast majority of people can see the need to suspend their social lives and to keep away from other people as much as possible, but there are times when they find themselves breaking the letter of the rules — perhaps because on occasion they find it difficult, if not impossible, to comply. So it is wrong, for example, to say that because there is more traffic on the roads than in April, this is a sign of non-compliance which requires a stronger police response, bigger fines or more government warnings.

The steady trickle of ministers and officials who have been caught bending the rules to suit them shows the problem. If those who advocate the rules find it difficult to abide by them, then it is hardly any wonder that the general population might also struggle at times. As Matt Hancock accepted in an interview with this magazine last week, some of the rules introduced for the first lockdown — such as preventing people from attending funerals of loved ones — were simply inhumane.

It would be possible to tighten things further. There are calls to suspend freedom of worship, to close nurseries, to stop people taking a walk with a friend. But ministers would struggle to quantify what difference such measures would make to the pandemic. With fatalities growing, they are increasingly desperate and may feel compelled to show they are doing something, even if tightening the rules would make no meaningful difference to the spread of the virus. In doing so, they would risk pushing people too far and undermining the broad compliance that we have seen for almost a year now.

A more humane balance is being struck this time, and this approach is all the more effective for its broad public support.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in