It was gratifying to see such a quiet and impeccably made film as The Dig make it to independent cinemas even though it was soon available to everybody on Netflix and is now their number one film. It’s the story of how the Sutton-Hoo treasure (all that glory of gorgeous blues and golds from an Anglo-Saxon burial ship) was unearthed in Suffolk in 1939. It stars Ralph Fiennes as the working man excavator who realises what all this means and Carey Mulligan as the ailing upper- class woman on whose property this radiant instance of Dark Ages art and culture was found. It is also directed by Australia’s Simon Stone who has been looking more and more like an actor’s director since his earlier stage experiments with Wild Ducks in glass boxes and Cherry Orchards (that somehow duplicated Chekov line by line when they were claiming to paraphrase him) have been supplanted by big-time casting and dramatic conceptions. Admittedly, even then he could elicit something like Robyn Nevin’s revelation of a performance in Neighbourhood Watch and more recently he has done the staggering production of Lorca’s Yerma with Billie Piper at London’s Young Vic and just a year ago the Brooklyn Academy of Music production of Euripides’ Medea with Rose Byrne.

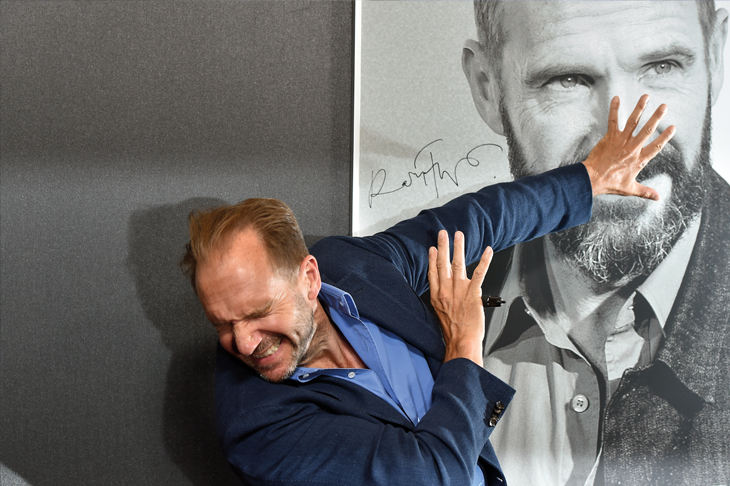

The Dig is done with such monumental restraint that it actually looks like an examination of Britain at the edge (and over it) of the declaration of war on Germany. Carey Mulligan is not so much losing her looks (as a friend suggested to me) as doing everything in her power to look like that grand old dame Wendy Hiller. She limps, with a stick, very erect and very frail, and she does that very difficult thing, she plays a woman in middle age while she’s still young. It is a flawless unshowy performance and so is everything in this film. Ralph Fiennes by necessity dominates out of sheer presence but there isn’t the faintest hint of aristocratic brio in this portrait of a serious man of integrity – at least as remote from his usual flexible high persona as his cockney hardman from In Bruges. And Stone and his producer Gabrielle Tana somehow ensure that the whole cast is in a kind of period camouflage which is impressive rather than pedestrian because The Dig has a kind of neo-sub-Chekovian restraint which gives a wholly moving quality to this array of stiff upper lips in the vicinity of understated emotional hardship.

Carey Mulligan is dying and is intent on her little boy who is conscious of her needs and of his own failure to nurture. Ralph, in his sturdy way, tells him, in his piercingly accurate sounding Suffolk accent, that we all fail every day but that he and his sturdy wife, Monica Dolan (remember her as Regan in Ian McKellen’s Lear and Masha in The Seagull) will look after him. Meanwhile Lily James, looking notably ordinary in specs, realises her husband Ben Chaplin gets a good deal more fired up about Eamon Flack (who played the Ripley figure in Joanna Murray-Smith’s Patricia Highsmith play Switzerland) so she falls for Johnny Flynn who has just joined the RAF.

Ken Stott has a competitive professional attitude to the grandeur of the find which is in tension with Fiennes’ and ensures the haul goes to the British Museum.

The Dig is a quiet piece of what could be semi-documentary drama and if it is smallish in its dramatic ambitions it nonetheless achieves an effect of infinite riches in a little room. Everything is unobtrusive and understated but there is not a wasted line of dialogue or an excrescent camera angle. Simon Stone, who looked like a bit of a vaunting auteur in his early stage days in Australia, seems to have learned everything about what film can do when considerable riches, histrionic and compositional, are used with great economy and restraint.

There are moments in The Dig when we want to weep at the sheer musicality with which tiny and fragile things are given their due.

It’s a period piece in the fullest and richest sense because it elaborates a world we have lost in the context of one of the grandest of all archeological finds. Carey Mulligan actually speaks in old-style received pronunciation which is a degree posher than the Queen’s now is.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in