On eBay I have an alert set for ‘Scottie Wilson’. Nine times out of ten, it’s a diamanté Scottie dog from the jewellers Butler & Wilson. Once in a while, it’s a gem.

Scottie Wilson didn’t think much of journalists. Art critics were ‘just jugglers — dodgers’. The sort of people who went to art shows — his or anybody else’s — could be counted on to go about ‘blabbing a lot of stupid muck. A lot of blah blah. They get paid for it too!’ Which makes it tricky to write about Scottie (always Scottie, never Wilson). You just know he’d light a cigarette and scowl.

I came late to Scottie. I thought I was good on artists between the wars, but I’d never come across Scottie or his works until I spotted — and instantly coveted — one of his Royal Worcester plates on a curator’s kitchen dresser. Since then, I’ve been on the scout for Scottie, on eBay and elsewhere.

Scottie has been called a ‘primitive’ or an ‘outsider’ artist. Hopeless terms, really. Ragged nets to catch a lot of queer fish. Maori bushmen are primitive, Henri ‘Douanier’ Rousseau is primitive, African carvings are primitive, the paintings at Lascaux are primitive, Alfred Wallis is primitive. All it means is: didn’t go to school, or didn’t go to the right school, or didn’t get into the salon, or didn’t play the game.

If Alfred Wallis is better known than Scottie it is partly down to famous friends — Ben Nicholson, Christopher Wood, Barbara Hepworth — and partly a case of having a good haul of his works in one place and out on display at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge. Scottie is more scattered: some at the National Galleries of Scotland, some at the V&A, most in private collections. The Tate has his flat cap and his famous ‘Bulldog’ pen.

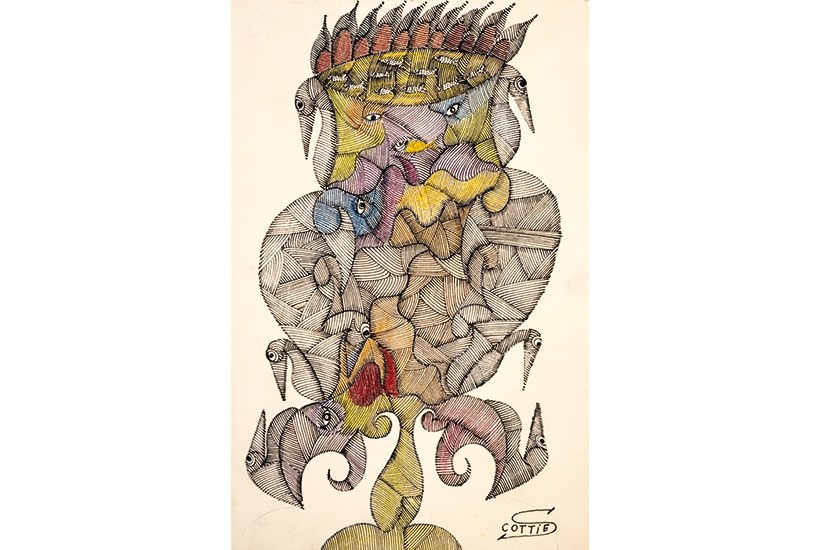

The pen was part of the Scottie myth. And how Scottie liked a myth. Never the same story to the same person twice, never a checkable name or a date. The pen, thought Scottie, looked a lot like a bulldog. You can see it on the Tate website: a stocky, wide-barrelled thing. The Bulldog lived on a card table at the back of Scottie’s Toronto schmutter shop. The baize on the tabletop was worn out and covered over with cardboard. It was 1932 (or thereabouts) and Scottie was 44 (or so). One morning, or afternoon, or evening, with the radio playing a Mendelssohn concert, Scottie began to draw. He could not stop. He did not stop for 40 years, not until his death in 1972. He covered the table, he covered the walls. He drew suns, trees, birds, flowers and orchids unknown to taxonomy. He created his own heraldic devices: beaks and petals, spines and eyes. He called his creatures ‘greedies and evils’ and set down their bizarre physiognomy in thousands of closely hatched strokes. He invented freely and recorded minutely. His work doesn’t spring from the imagination so much as crawl out from under the bed. ‘Don’t ask me what they mean,’ he used to say. ‘If you don’t know I can’t tell you.’ He never gave his pictures titles and preferred drawing pins to proper frames.

Scottie was born Louis Freeman (no relation, as far as I know) in Glasgow on 6 June 1888 to a working-class Jewish family originally from Lithuania. His father was a furrier, said Scottie. (A taxidermist’s assistant, said others.) Scottie worked as ‘a barefoot newspaper boy’, then as a push-barrower. He fought for the Scottish Rifles on the Western Front in the first world war and after demobilisation ran a stall on the Caledonian Road. In the 1920s, Scottie left for Canada where, circa sometime or other, he first got going with the Bulldog pen. Asked if there wasn’t something of the native northwestern totem pole to his pictures, the artist hummed and hawed. ‘Yes, that’s true, but the totem poles are my totem poles.’

Scottie was small and short-tempered, unmercenary but cynical. ‘If there’s one thing the world loves,’ he used to say, ‘it’s a bargain and a scapegoat.’ George Melly, the jazz singer, film critic and art historian, thought Scottie looked like ‘Doc’ in Disney’s Snow White, only with an incriminating ‘grog-blossom’ nose. Scottie liked his Woodbines and his whisky.

Evelyn Waugh had a dig at Scottie — or Scottie’s fans — in The Loved One. Sir Francis Hinsley, reading a copy of Horizon, complains to Dennis Barlow: ‘Kierkegaard, Kafka, Connolly, Compton-Burnett, Sartre, “Scottie” Wilson. Who are they? What do they want?’ Sir Francis points to a page: ‘Those drawings there. Do they make sense to you?’ No, says Dennis. No, says Sir Francis.

Do Scottie’s drawings make sense to me? No, but the pleasure is all in the puzzle. In 1965, Scottie was invited to design a dinner service for Royal Worcester. It is these marmalade jars and coffee pots that occasionally turn up on eBay. There’s a Scottie swan-pattern saucer on the wall above my breakfast table. I’d swear it’s giving me the eye.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in