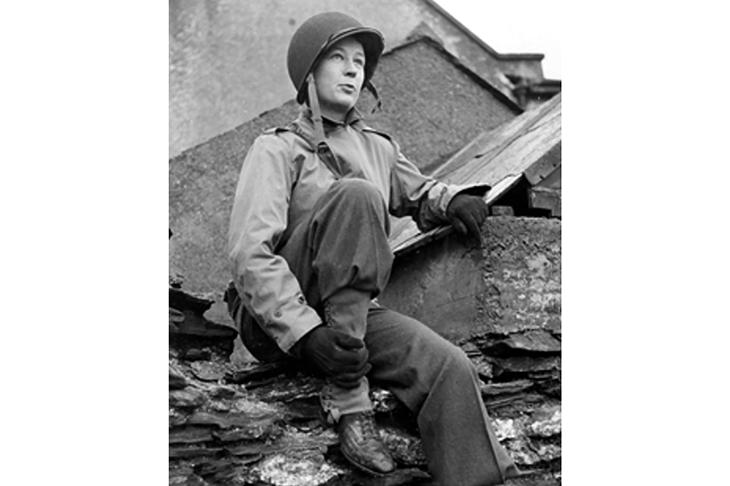

Two war correspondents were hitching a lift towards Paris in August 1944 when a sudden wave of German bombers forced them to dive for cover. What the hell were they doing trying to cadge a ride when ‘war correspondents have their own jeeps and drivers?’ an American officer barked at them as his car screeched to a halt beside the shallow crater they had commandeered. ‘We happen to be women,’ Ruth Cowan replied steadily, as she straightened up and shook off the dust along with his words.

Cowan was the first female journalist attached to the US army but, as a woman, she was denied the official facilities provided for the men of the press. At the outbreak of hostilities, British female correspondents were prohibited from combat zones. Once they joined the war, the Americans were more flexible, prompting many Brits to seek US press accreditation. Even the American war department only permitted women at the rear of the action, however, and denied them access to official transport, sleeping arrangements, military briefings and the press censors, teletypists and radio transmitters needed to file their copy. (The women were each provided with two tailored skirts, though — one khaki and one pinkish-grey for evening wear.)

Official objections to calls for equal terms were centred around concerns for the women’s safety and the double bind of ‘inevitable trouble’ should a woman be embedded with a division of male soldiers, along with fears that the men’s ‘natural chivalry’ might lead them to prioritise female safety above their military mission. There was also the ever concerning ‘cloakroom question’. Women’s ability to cope was apparently beyond the military imagination, yet ironically, as Judith Mackrell’s compelling book shows, navigating newspaper bias and military restrictions often gave women the professional edge.

Mackrell focuses on the work of six journalists whose lives intersected as the second world war progressed. Sigrid Schultz, the first American woman to run a foreign press bureau, was based in Berlin until forced to flee. She was a self-proclaimed feminist with a secret Jewish heritage, so her attendance at Goebbels’s propaganda screenings was strikingly courageous.

Martha Gellhorn and Lee Miller, the most famous of the set, were deeply affected by what they witnessed, providing plenty of powerful copy to keep these pages turning. Most famously, when no women were included among the 558 official press and radio journalists approved to cover D-Day, Gellhorn stowed away on a hospital ship bound for Normandy. Helping to retrieve wounded soldiers from Omaha Beach, she was much closer to the action than most of the press corps.

Virginia Cowles, apparently forever in high heels, brought more objectivity to her reports, the skills she had honed during the Spanish civil war belying her glamorous appearance. When Helen Kirkpatrick was told by the Chicago Daily News: ‘We don’t have women on our staff’, she replied: ‘I can’t change my sex, but you can change your policy’ — which they did. She had many scoops, from the invasion of Belgium to the sniper attack on De Gaulle after the Armistice. Clare Hollingworth, the only Brit, best known for breaking the story of the Nazi invasion of Poland that precipitated the world into war, was perhaps the most defiant of all. Having escaped Poland, witnessed two armed coups and dodged several arrests, she had little time for press diplomacy or the attitudes of men such as Montgomery who, when hearing of her arrival, declared: ‘I’ll have no women correspondents with my army.’

Collectively, these determined, courageous and accomplished reporters covered many of the key battles and engagements of the war. Although female correspondents were light on the ground in the Pacific theatre and on the Eastern Front, Mackrell gives honourable mention to those who were there. Often forced to use ‘illicit or ingenious means’ to reach Allied combat zones, the women repeatedly found fresh perspectives en route, while being barred from army press briefings released them from having to toe the official line. Free to consider the human as well as the military angle, their stories were all the more powerful and engaging.

My only gripe is with the title. ‘I am going… with the boys,’ Gellhorn wrote as she first set off for war; but she was soon disappointed by the mediocrity of some of ‘the boys she had been so impatient to join’. Although male reporters were always given priority, it seems a pity to relegate the women to the subtitle of their own story.

The history of the second world war has largely been told by, for and about men. The story of these six correspondents covering the battle zones of Europe and North Africa stands as an important corrective. These women aspired to be treated as reporters first and women second, but ingrained prejudice meant that their experiences and perspectives were very different to those of their male colleagues. They were not just reporters; they were also pioneers, and Judith Mackrell has done them proud.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in