Manchester, in the words of the artist Linder Sterling, is a ‘tiny little world’. Nearly three million people live in its sprawl, but its centre is compact. Like-minded Mancunians have always found one another easily. Cultural life is febrile, which partly explains how, in the pre-digital late-20th century, England’s third city produced such startling bands: Joy Division, the Fall, New Order, the Smiths, the Happy Mondays and Tony Wilson’s era-defining Factory record label — and Buzzcocks, less celebrated, but without whom Manchester’s creative energy would have failed to detonate.

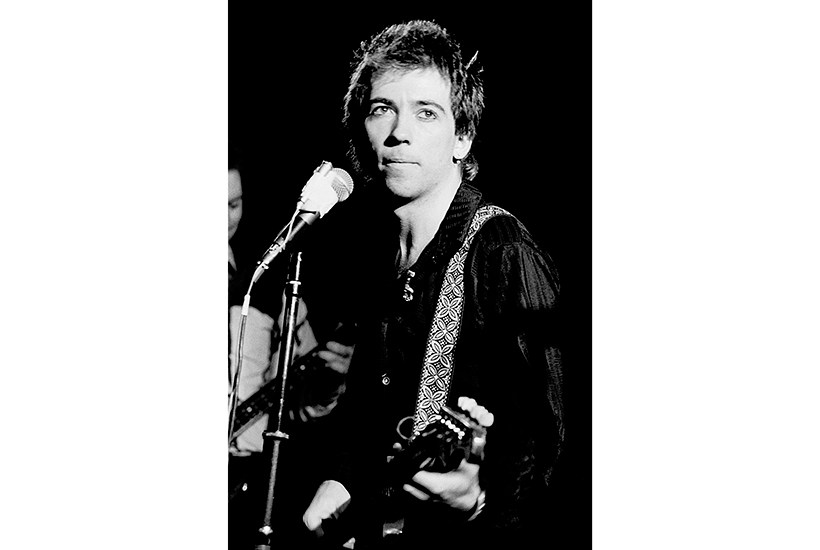

Pete Shelley was Buzzcocks’s charismatic co-founder and chief songwriter, whose sharp lyrics and bratty vocals shaped much of British punk. He died in 2018 without leaving a memoir, though he would have written an excellent one: he was erudite and well-read. But he did record interviews with his friend Louie Shelley (she is no relation — Pete was born Peter McNeish, Shelley was his stage name). Louie has published a short text and the interviews verbatim in Ever Fallen in Love, which focuses on the band’s ‘blistering years’ between 1975 and 1981.

This is fan writing: instinctive, not overly analytical. Louie is a Buzzcocks obsessive; her commentary is straightforward and the interviews friendly. Unlike much modern music writing, there are no quasi-academic treatises or earnest explanations of why Buzzcocks ‘matters’. This is punk — of course it matters. Her enthusiasm and rigour are her strengths.

In the late 1970s Buzzcocks made three albums and a few standalone singles, what Louie calls ‘divine pop delicacies’ — urgent, witty tracks with power-pop chords and ‘sudden endings to frighten DJs’. Spiral Scratch, their first EP, released in January 1977, was one of the earliest British punk records and pioneered independent record labels, pre-dating Factory.

Working-class, academic-leaning bands with little money were resourceful (Shelley and co-founder Howard Devoto were grammar-school and FE-college products). Spiral Scratch was paid for by what would now be called crowdfunding and released on the band’s own label. Artistic aspirations had to fit around day jobs. Pete worked as a trainee computer programmer at the National Coal Board, processing redundancy cheques — as symbolic of post-industrial decline as is possible to imagine. ‘Boredom’ — ‘You know me, I’m acting dumb/You know the scene — very humdrum’ — was written by Devoto on a factory shift.

Pete, meanwhile, specialised in that un-punk subject, love. It is hard to think of a more brutal, economical and exquisite portrait of doomed romance than ‘Ever Fallen in Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve)’, with its opening punch: ‘You spurn my natural emotions/You make me feel like dirt — and I’m hurt.’

As Louie points out, Pete’s lyrics had more in common with the drollery and disaffection of the Smiths than the fighting anthems of contemporaries such as the Clash (Morrissey was a huge fan). Pete was bisexual; and punk, he tells Louie, gave him the freedom to discuss human relationships: ‘Love is compulsion and obsession, betrayal and exploitation, disappointment and regret.’

It is heartbreaking stuff, though not particularly seditious. But Louie points out that the band was punk’s connective tissue. The old story about how the movement changed from an obscure London scene to a cultural phenomenon at Manchester gigs arranged by Buzzcocks is retold here. It may be true or it may be exaggerated, but it is an irresistible tale.

In the summer of 1976, Pete and Howard persuaded Malcolm McLaren to bring the Sex Pistols north, with two performances at the Lesser Free Trade Hall on Peter Street, part of a grand Victorian venue once home to the Hallé Orchestra. (Buzzcocks did the work, printing and selling tickets and pasting posters around the city; McLaren loitered on the pavement, cajoling passers by inside.)

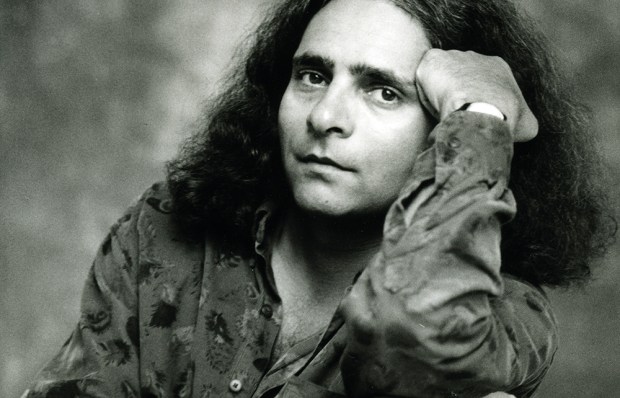

They were tiny gigs, what Morrissey described to the writer Jon Savage as ‘a front-parlour affair’, but Manchester’s like-minded turned up: Sterling, Morrissey, Wilson (then still an unlikely regional TV presenter), Peter Hook, Bernard Sumner, Mark E. Smith.

Soon after, Devoto left to form Magazine, and Buzzcocks signed to United Artists. As Wilson noted, the music arm of the great Californian company was founded by Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, which Wilson thought fit Buzzcocks lineage. The label brought them money, introduced them to the US and gave them creative freedom, including the choice of subversive and explicit artwork by their Manchester artist friends Malcolm Garrett and Sterling. These alone are extraordinary, in that they presage 1980s graphics. That gorgeous Buzzcocks ephemera is reproduced in the book.

Today, Manchester is full of international tourists, drawn by its music legacy. What was once the Lesser Free Trade Hall is a five-star Radisson hotel. Factory closed in 1992, but a £186 million international performance venue, also called Factory, is due to open in December.

Where do Buzzcocks fit into all this? Louie’s book is not a grand narrative, and perhaps the band will be under-celebrated until someone writes such a thing. Instead, she offers us fascinating minutiae: the circumstances behind Pete’s lyrics, how the band came together, and why. Her diligent probing illuminates the Manchester of nearly half a century ago — how a tiny world became a cultural sensation.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in