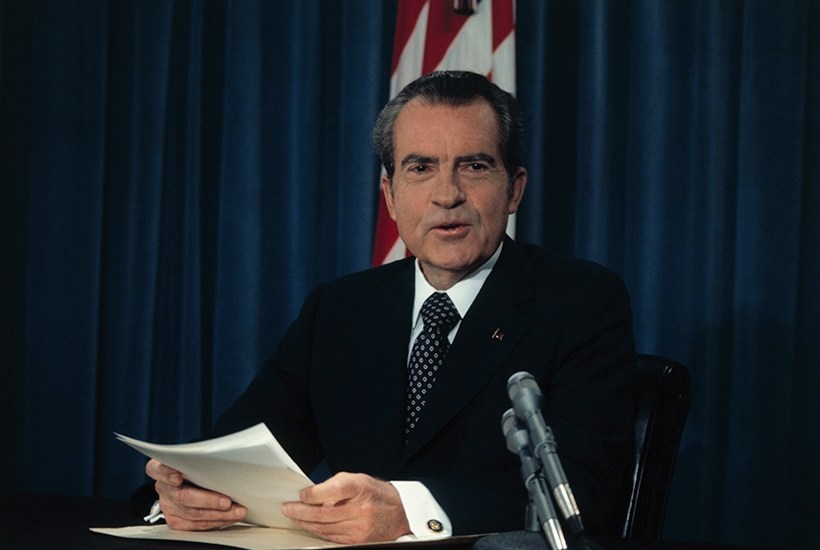

In this Age of Trump, as we cast about for some moment in American history that might help us make sense of the present, the name Richard M. Nixon keeps resurfacing. Nixon, who resigned the presidency in 1974 after being swept up in investigations into the crimes and cover-ups known collectively as Watergate, offers easy comparisons with Donald J. Trump: two corrupt American presidents who left office in disgrace; who considered the press their enemy; who accused the previous administration of surveilling them; who weaponised racism as a way to win elections; who employed the politics of division as a way of keeping power; who possessed and indulged an outsized thirst for revenge.

As investigations now swirl closer to Trump, Watergate prosecutors and the whistleblower John Dean have resurfaced to remember Nixon’s rise and fall. Watergate is America’s ur-scandal, and, in living memory, the closest analogue to the political traumas the country has recently endured. These comparisons make the British-born journalist Michael Dobbs’s King Richard as of the moment as it proves to be ultimately timeless.

It would be next to impossible to frame a tragedy about a man who, say, exists only to exalt himself, and who owes his every victory to family wealth and brazen self-promotion. But it’s entirely possible to compose a tragedy about Nixon, a man whose hardscrabble life and rise from nothing embodies multiple American myths, and that is precisely what Dobbs has done. This beautifully written and stunningly detailed portrait of 100 essential days at the beginning of Nixon’s second term brings the Watergate scandal, its colourful cast of characters and Nixon himself to life in a way we’ve never before seen.

Dobbs’s deep dive into the conversations that Nixon obsessively recorded (3,700 hours of them were released in 2013) gives the book amazing authenticity. We listen as Dean tells Nixon that his closest aides could be charged with ‘obstruction of justice’, a section of the legal code ‘as broad as the imagination of man’, and Nixon breaks down as he talks about firing those same aides:

The problem I have is that I can’t look at it in the detached way I really should: these people, they’re guilty, throw them out, and go on. Just the personal things are… Goddamn, I think of these good men.

King Richard feels like a proper tragedy, beginning as it does at the high point of Nixon’s long political life. He wins his second term in a landslide victory over the Democrat George McGovern, taking 49 of 50 states and holding a 68 per cent approval rating as he returns to office. But the seeds of his fall — his hubris if you will — are already planted: the break-in to the psychiatrist of Daniel Ellsburg, who leaked the Pentagon Papers, and the capture of hapless burglars who had intended to bug the Democratic national headquarters to benefit Nixon’s re-election. By the end of the book, although we do not witness Nixon’s fall, we feel it looming. And we recognise, in good tragic fashion, the story of a person who makes sacrifices and cuts corners to get what he wants, onlyto discover that the goal was unworthy of those moral compromises.

The Nixon we meet in these pages is not just a power-mad monster; he has a deeply human side. In addition to occasional self-pity, he feels genuine remorse over the suffering his aides endure. His family don’t simply serve as political props or sycophantic yes-children. He loves his daughters, Julie especially, and pauses in whatever he is doing to take her calls. ‘If he was in the middle of a meeting and received a telephone call from Julie,’ Dobbs records, ‘his voice would change instantly from imperious and irascible to loving and caring.’ It’s difficult to imagine Trump reacting with similar affection to any of his children,let alone exhibiting Nixon’s remorse at having to say: ‘You’re fired.’

The vulnerability of Dobbs’s Nixon does not erase his bigotry, paranoia and ruthlessness. But it makes him recognisable to us, a sweaty Lear with a widow’s peak, a Macbeth bathed in the blood of American soldiers who fell in Vietnam as he negotiated peace, a Hamlet who lets the kingdom fall to pieces as he hesitates. The Richard Nixon who emerges in this story is not admirable, but he is fully human, endowed with gifts as well as massive flaws. That man is, Dobbs concludes, ‘an unfathomable mixture of idealism and cynicism, greatness and pettiness’, and King Richard’s vivid characterisations, novelistic detail and universal human themes make this a work of our time and for all time.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in