It must have been shortly after my first performance of Not I in London in 2005 when Matthew Evans, the former chairman of Faber, handed me a volume, published in 1992, of The Theatrical Notebooks of Samuel Beckett.

He told me that the series was no longer in print and therefore difficult to get hold of, but he dearly wanted me to have this copy. It was volume 3 — Krapp’s Last Tape, one of the two of the series (the other being Endgame) that Beckett himself had approved and personally overseen the edits for. Doing so had prompted Beckett to make further adjustments to the play text, despite it having been published more than 20 years earlier — such was his own artistic process of obsessively tinkering with and amending his work.

In fact if there is only one reason to turn to these particular notebooks it is to witness an artist who was in constant transition — who realised that, unlike the static, finite nature of prose text, theatrical work was, and always is, a changeable art form.

But the personality of a pulsating medium in a constant evolutionary process is unfortunately incongruous with the publishing business. So if you were looking to discover the final text of any given Beckett play following his death, you would have done well to arm yourself with the most up-to-date amendments found in these notebooks — if you could afford it.

Today, if you are lucky, you can purchase the same hardback copy of Krapp’s Last Tape for anywhere between £600 and £1,000 on eBay. So until Faber’s paperback republication of the series, an actor would have had to cough up more than an entire week’s salary to access the nearest version possible to any ‘complete’ working text.

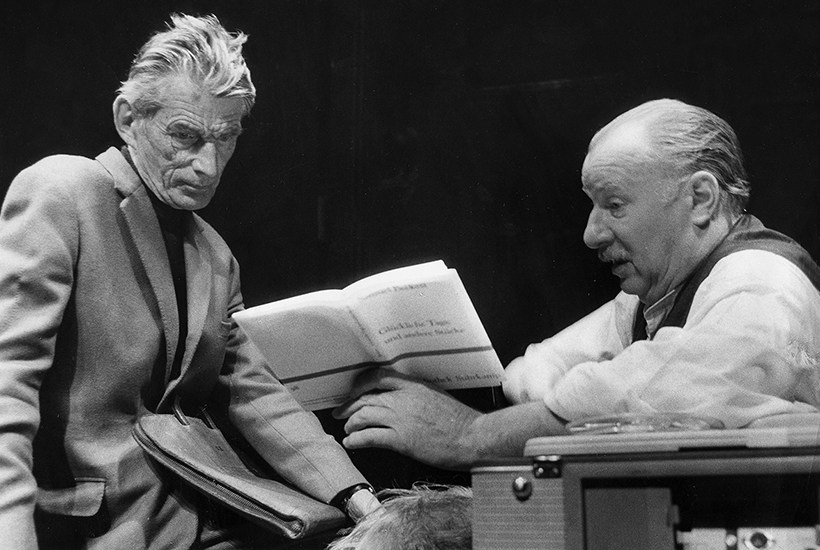

Beckett was a consummate director of his own work, and kept copious notes during his rehearsal periods in London and Berlin, which are reprinted in facsimile here. While these notebooks brilliantly refute any idea of a definitive text, they also throw into question Beckett’s infamous and misguided reputation for ‘rigidity’. While Beckett is of course very exact and specific in his stage directions, punctuation, musicality and the structure of his work, these texts more than demonstrate his appreciation of the theatre’s fluid nature.

Beckett is much more of an installation artist in this regard than a straight playwright. Through the process of working with his actors; with directorial approaches refining his images with the tools of light and sound; ‘failing better’ by working closely with his material in performance and production… the plays themselves were constantly being distilled and clarified right to the end.

The editors, James Knowlson and Stanley Gontarski, both of whom are highly regarded Beckett scholars, do well to decipher Beckett’s next-to-illegible thin scrawl, and diligently take note of his abbreviations in English, French and German, even forensically looking beneath his erasures. The texts are densely documented with Beckett’s stringent and constant self-editing, alterations, rewriting and, of course, his lists.

For those of us who know both Beckett’s oeuvre and theatre intimately, it’s easier to feel comfortable here — and understand more readily why he made certain changes, choices and tweaks, seeing time and again evidence of his need to further refine his language, remove any sentimentality, make adaptations for individual actors, hone his imagery to work within the confines of the space and always to make it more pertinent for the audience.

But these notebooks provide no Virgil-like figure to guide or interpret through the Commedia of Beckett’s mind — and neither do they provide any kind of broader context or intertextual exploration. They do not explore how these plays might be in conversation with any of Beckett’s other prose work, his poetry or biography, nor explain the constantly repeated motifs, images and voices found in them. They do not attempt to establish any clear trajectory of his work even within this series.

The publishers have made no revisions to this paperback edition, and not all the texts have the latest amendments: often missing are elements from the Schiller notebooks, not to mention Beckett’s work in Paris and elsewhere. So it would be unwise to refer to this series as ‘complete’. There was an opportunity missed, too, to look at how the editors’ perspectives, and indeed our own relationships with the texts, have changed over 30 years of reading, performance and study.

During that period, what has proved constant is the degree to which Beckett’s words and ideas remain relevant and speak to our times. The greatest omission of all here is of a major work that speaks most directly to the present moment, Happy Days. That is bizarre, to say the least. The play is increasingly regarded as Beckett’s finest of all — and is certainly the most resonant with this moment of isolation and struggle we are living through today.

The production notebook of Happy Days was published in 1985 as part of the original series. That it has been abandoned for this republication is the final indignity for the play’s protagonist Winnie, in my view the greatest role ever written for a woman (who spends the play’s first act buried to her waist and the second up to her neck).

Still, the publication of these volumes gives us an opportunity to eyeball the artist in process. And while even here we find that there can be no definitive text that ‘explains’ Beckett’s work, this might be no bad thing. In Happy Days, Winnie recalls a wife’s retort to her husband’s question ‘What’s the idea?… What’s it meant to mean?’ ‘And you?’, she replies, ‘What’s the idea of you? What are you meant to mean?’ That is Beckett’s greatest provocation — both for himself and us.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in