Xi’s Cultural Revolution is now well under way and beginning to echo Mao’s Cultural Revolution (1966-76). There will, of course, be differences. After all, Mao’s era was characterised by pervasive poverty – unless you belonged to the party elite – while Xi’s China has high-speed rail, ambitions to colonise Mars and so forth. For all the obvious differences, though, similarities between them are real.

A Cultural Revolution might be broken down into various parts. In the first instance, we are talking about a naked power play. Mao Zedong did not appreciate being sidelined by Liu Shaoqi, Deng Xiaoping et al. even after his catastrophic Great Leap Forward experiment (1958-62) caused the death of up to 55 million people. The shock and awe of the Cultural Revolution allowed his so-called Cultural Revolution Group (later demonised as the Gang of Four) to mount a successful coup against the party politburo.

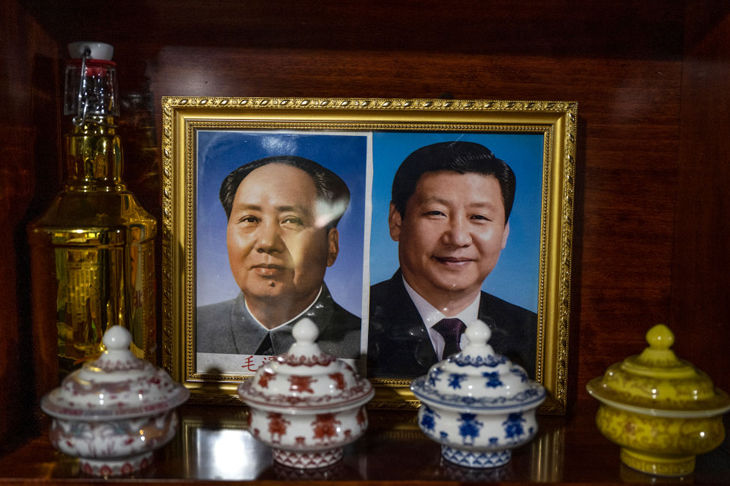

In some ways, at least, the death of up to 20 million Chinese people during the first two manic years of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was less about forging revolutionary purity in China than Mao getting his old job back as Great Helmsman. Xi Jinping, officially designated Helmsman in 2020, is now hellbent on creating a Mao-like personality cult of his own – or as much as one can without a compelling personality.

‘Xi Jinping Thought’ is currently being introduced into curriculum throughout China. We shall have to wait and see how it compares with the genius of Mao Zedong’s insights about the human condition: ‘To read too many books is harmful’; ‘Everything under heaven is in utter chaos; the situation is excellent’; ‘The Communist party must control the guns’; and ‘You can’t be a revolutionary if you don’t eat chillies’. A favourite aphorism from the demagogue responsible for more deaths than Adolf Hitler or Joseph Stalin would have to be this zinger: ‘It’s always darkest before it becomes totally black’.

Certainly, life appears to be turning dark and darker under Xi’s latest crackdown or what Mao would have called ‘sweeping away all the ox devils and snake demons’. The regime has introduced all-encompassing new regulations for everything, from video games to private tuition companies. Television programs, especially ones from the decadent West, are being culled. Xi’s Cultural Revolution is aiming to uproot ‘rampant pop culture’ and replace it with ‘the rewards of a moral society’.

Chinese film star, singer, entrepreneur and director Zhao Wei, despite having over 85.6 million followers on social media platform Weibo, has just been cancelled. Even an online fan group site dedicated to Zhao abruptly vanished. The billionaire celebrity joined a list of 25 stars erased from history over two days in late August. No longer will ‘improper idol worship’ be tolerated in the People’s Republic.

Improper idol worship of Helmsman Xi is another matter altogether. Xi – like Mao before him – has been careful to formulate his ‘common prosperity’ rectification campaign in terms of attacking the privileged and defending the poor. There is definitely an equity imbalance in China, with some 600 million people getting by on approximately $200 a month. At the other end of the scale, there are purportedly 400 more billionaires in the Middle Kingdom than in the USA. That said, the growing number of disappearing Chinese billionaires, from Zhao Wei to property developer Ren Zhiqiang, currently doing eighteen years for criticising Xi’s handling of Covid-19, might be a pointer to the future.

Soon, perhaps, the only billionaires in the PRC will be the 25 members of the party politburo. The same kind of grotesque hypocrisy was a feature of life during the original Cultural Revolution. The Private Life of Chairman Mao, written by Li Zhisui, Mao’s personal physician for almost twenty years, tells the tale of a Red Emperor who publicly proclaimed the joys of communist egalitarianism and self-sacrifice while denying himself none of the decadent pleasures of an imperial court.

Today a new Red Emperor is tackling the problem of ‘extreme wealth’. Meanwhile, he and his coterie live in exclusive and secluded compounds, including Zhongnanhai, a former imperial garden in the Imperial City. Xi’s extended family accumulated their first billion dollars as long ago as 2012, the year Xi came to power. A report filed at the time by John Garnaut claimed Xi’s older brother, Qi Qiaoqiao, acquired untold wealth on behalf of the family ‘beneath assumed names and layers of holding companies’. Nonetheless, Chairman Xi, even in 2012, made a point of lecturing new cadres on the value of studying ‘Mao Zedong Thought’ to ‘avoid the lure of money’.

Chairman Xi’s attempt to copy Chairman Mao can be embarrassing, including ditching the business suit in favour of a Mao party costume for his address in Tiananmen Square to celebrate the 100th birthday of the Chinese Communist Party. There was a time when China could not survive a single day without a wise and well-chosen word from the Great Helmsman. Those days are back! Now hardly a news bulletin goes by without Helmsman Xi cited as ‘urging’ one thing or another – France and Germany not to side with the US or China’s journalists to conform to the Chinese Communist Party.

Paramount leader Deng, himself a victim of Mao’s Cultural Revolution, had a choice to make in 1978-79 when the dissident Wei Jingshen critiqued the regime’s Four Modernisations strategy – agriculture, industry, science/technology and defence. In a wall poster and subsequently an essay called Fifth Modernisation, Wei insisted on the need for a guarantee of democracy and personal freedoms. Wei argued that without this, the return of Maoist totalitarianism was always a possibility – no amount of market reforms and opening the country up to foreign investment changed the fact that the political system remained a dictatorship of the Communist Party, an organisation that could no longer be trusted to modernise China given its track record over the previous thirty years.

Deng Xiaoping disagreed. He jailed Wei and subsequently dismantled Democracy Wall, confident that by introducing market reforms and adopting a somewhat more liberal attitude to the arts and literature, the party showed it could be trusted to not repeat the mistakes of the past. The de-Maoisation of China would endure, albeit with Mao’s perfectly preserved body on display within a crystal coffin in an ornate mausoleum off Tiananmen Square. How wrong can you be?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in