The extent of Walt Disney’s grasp of the natural world remains unclear. After the Austrian author Felix Salten sold the rights to his 1923 bestseller Bambi for a paltry $1,000, Walt is reputed to have suggested myriad unhelpful plot additions to the simple story. ‘Suppose we have Bambi step on an ant hill,’ he offered at one script meeting, ‘and then cut away to see all the damage he’s done to the ant civilisation?’

His writers knew better. The resulting 1942 forest fantasia, which leaps in swooning bounds from one extravagantly coloured and orchestrated natural history lesson to another, was nominated for three Oscars, and by 2005 had grossed $102 million.

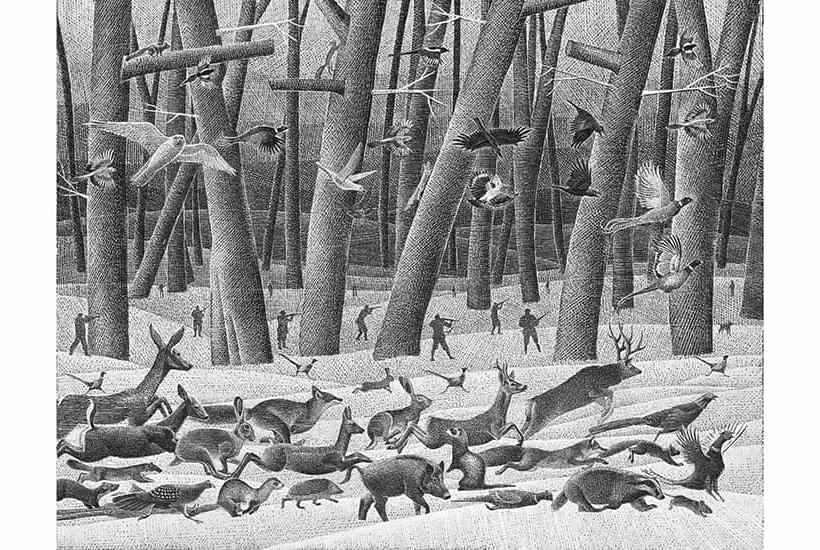

The original author did less well out of his gambolling creation. Salter never saw a penny of the Disney movie’s global success and died alone, forgotten, in exile. He had fled to neutral Switzerland from his homeland of Austria because — as it may surprise some to learn — Bambi, along with Salten’s other works, was on a list of books banned by the Nazis in 1935. For, as this elegant, uncompromising new translation by the American academic Jack Zipes (with suitably shadowy illustrations by Alenka Sottler) makes clear, it is not really a children’s book at all.

Salten’s basic plot — the bittersweet Bildungsroman of a young deer — will be familiar to fans of the movie. The book begins enchantingly enough, with Bambi’s mother educating him on the difference between a butterfly and flower. Bambi develops from naive fawn to grand old prince of the woods, coming of age through the rites of love and loss, teaching himself, and us, about the ever-changing natural world as he does.

The eponymous deer is not the only character Disney fans may recognise either: there is Faline, the skittish object of his affections; a harrumphing screech owl to dispense aged wisdom; and plenty of romping squirrels. But if you were one of many children traumatised by an unseen hunter shooting Bambi’s mother in the Disney film, consider this your trigger warning: what follows is far bleaker.

By the book’s end, the woods have turned very dark indeed. Not only does Bambi lose his mother, but nearly every single animal endures brutal suffering or a bloody end. ‘It was quiet in the forest, but something horrible happened every day,’ begins one chapter cheerily. And not just thanks to human hunters. A crow attacks the hare’s son ‘in a cruel way’. A squirrel finds himself unable to talk any more, thanks to the pine marten biting out his neck. A fox tears apart the ‘strong and handsome pheasant who had enjoyed general respect and popularity’. This is a tale of everyday country creatures who live in terror.

Perhaps the cruellest sequence concerns Bambi’s young deer chum Gobo (replaced by Thumper the rabbit in the Disney version), who is shot, wounded, taken in by a human, nursed and fed, then released back to the forest with a heartening message. The human — known throughout only as ‘He’ — is not to be feared after all. ‘If somebody serves Him, He’s good to him. Wonderfully good!’ Not long after dispensing this happy news Gobo is shot again, this time fatally, by another hunter.

By the time a hound on the trail of a trapped fox is surrounded by a mob of baying forest creatures denouncing him as ‘Traitor’ and ‘Henchman’, we are straying into Animal Farm territory, and the real target of this fable becomes clear.

Salten was both a hunter and a passionate advocate for animal rights. And he was also a Jew, living for a time in occupied Austria. As Zipes makes clear in his introduction, he was a man who hoped to overcome his own contradictions through literature, who believed that ‘only when people truly understood how the animals suffered persecution from hunting in the forest could they create peace among themselves’.

Bambi, both book and film, are no advert for blood sports. But Salten’s allegory derives its real power from the experience of anti-Semitic alienation, persecution and genocidal slaughter played out in a grimly ironic woodland paradise. The animals try to be good, to be kind, to survive; yet every path taken — escape, assimilation or concealment — leaves them only more exposed to ruthless cruelty.

John Galsworthy wrote an enthusiastic foreword to the original, much more innocuous translation, in which he extolled the book’s appeal to conservationists, with the dry conclusion: ‘I particularly recommend it to sportsmen.’ Had he read this version, he might have added ‘and autocrats’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in