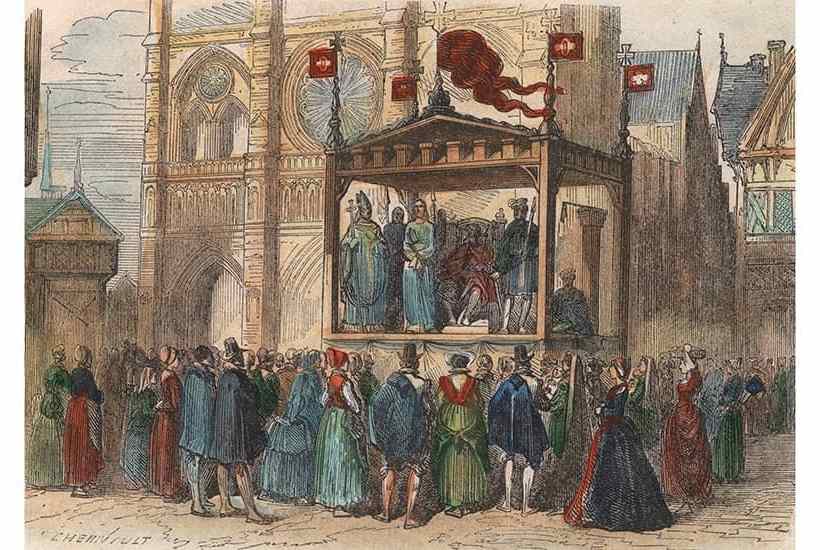

In The Archers, Ambridge put on its own set of mystery plays dramatising the Nativity and Passion. BBC Radio 4 broadcast them separately from the soap opera, in which the village policeman has been driven to conversion by playing Jesus.

My husband, commenting on all this, said that ‘of course’ the word mystery meant a trade or craft, as the medieval plays were performed by companies of trade guilds. He might have been reading the website of the Chester Mystery Plays, due for their five-yearly performance in 2023: ‘The word mystery comes from the French mystère meaning “craft”, and apprentices joined the guilds to learn their mystery or craft. When the guildsmen began dramatising the Bible stories, their plays thus became known as Mysteries.’

Not so fast. There are two words mystery. One comes from Latin mysterium (‘secret’), itself from Greek mysterion, ‘mystery’. The other is from Latin ministerium, ‘office’, which in the Middle Ages came to mean ‘guild’. The exact phrase mystery play is modern, first cited from Walter Scott in 1808. The guilds did put on what we call mystery plays, but mysterium in late medieval Latin could on its own mean a Passion play. The Oxford English Dictionary concludes that ‘it is uncertain whether this sense is at all influenced by or connected with’ mystery in the sense of ‘guild’.

Chaucer talks of pleyes of myracles, and attempts have been made to distinguish between miracle plays about saints and mystery plays about biblical events. Historically the distinction was not consistent. To compound confusion, a mystery meaning ‘trade’ became mixed up, from the 16th century onwards, with the technical mysteries of a trade. Hannah More, in a novel of contemporary life written in the time of Walter Scott, observes: ‘No man is allowed to set up in an ordinary trade till he has served a long apprenticeship to its mysteries.’

To tangle the skein still further, mastery of a trade was confused with the word mystery. In the Middle Ages, man of mister meant ‘craftsman’. But our word mister, spelt Mr, is only a variant of master. My husband is a Dr, not a Mr, yet he is a master of confusion.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in