It started with Henry Kissinger. Before Intel apologised to China for attempting to remove forced labor from the company’s supply chains in December, before Disney thanked a Chinese public security bureau that rounded up Muslims and sent them to concentration camps, before LeBron James criticised the Houston Rockets’ general manager for supporting democracy in Hong Kong, before Marriott fired an employee for supporting Tibet, before Sheldon Adelson personally lobbied to kill a bill condemning China’s human rights record, even before Ronald Reagan called China a ‘so-called Communist country,’ the men whose relationship became a blueprint for everything that came after sat with Premier Zhou Enlai in a Chinese government guesthouse in July 1971, discussing philosophy.

By his flattery, persistence, and charm over dozens of hours of conversation over five years, Zhou initiated US National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger as a friend of China. The friendship wasn’t merely diplomatic, or coldly strategic. The former assistant secretary of state Richard H. Solomon, in a formerly classified study about Chinese negotiating behavior, described Kissinger’s memoirs of the time as ‘replete with almost awestruck recollections of the personal escorts, elaborate tours, and lavish banquets meticulously arranged by his Chinese hosts during his nine visits between 1971 and 1976,’ the year that Chairman Mao Zedong and Zhou died. It was during these years that Kissinger helped bring isolated China back into the world order, and it’s when he became known as a friend by Zhou. Kissinger’s admiration persisted. ‘In some 60 years of public life,’ Kissinger writes in his 2011 book On China, ‘I have encountered no more compelling figure’ than Zhou.

Kissinger’s trips to China in the early 1970s were monumental not only for reestablishing a relationship between the two countries. They also inaugurated two distinct but interrelated phenomena that still shape America – and the United Kingdom, among other countries – today. The first is how Beijing employed tactics of the United Front – a Leninist concept of cultivating friends and weakening enemies of Communism – to shape American politics and business. The second is the rise of what could be called diplomat consultants – like former US secretaries of state Alexander Haig Jr. and Madeleine Albright, and former British Prime Minister Tony Blair – who fit into the long-standing Chinese tradition of trading access for accommodation. Increasing exposure to China did bring immense benefits to America’s economy and helped encourage millions of Americans to spend time in China. These are very real upsides, and they should not be ignored.

At the same time, these diplomat consultants are like field agents of Party influence, especially in the business world, where they help global firms compete and cohere to Party standards while instructing these same firms on how to chill anti-Party speech. And in the years since Kissinger established his consulting firm Kissinger Associates in 1982, Kissinger began to open doors for American companies in China – while actively dampening criticism of the Party amongst his massive network. Starting in the early 1980s, Kissinger would frequently adopt a reverential and sentimental tone towards China, out of character for the textbook realist. From the George HW Bush administration, where he argued for a lighter response to the June 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, to the Trump administration, which he reportedly convinced not to meet with the Dalai Lama – Trump was the first president since Reagan to not meet with the Tibetan spiritual leader – Kissinger used his considerable government influence to weaken policies that targeted Beijing.

Kissinger declined multiple interview requests. One of his representatives denied that Kissinger was an agent of Chinese influence, and called the allegation libellous. Kissinger’s relationship with China, he said, ‘is in the highest and best tradition of American statesmanship.’

All intelligence agencies recruit foreign agents. But the Party’s relationship with its American friends, Kissinger included, is different, because of the Party’s expansive attitude toward espionage. There are two major differences between Washington’s and Beijing’s views on intelligence gathering. The first involves the deeply political nature of the Party’s intelligence and security services. In China’s intelligence agencies, like in many branches of its government, political commissars and Party secretaries work with their more technocratic counterparts to ensure the agency and its staff follow the correct political lines. ‘The Ministry of State Security People’s Police are red troops loyal to the Party,’ a ministry spokesperson said in January 2021, in reference to an internal Chinese police force.

The second is Beijing’s reliance on a wide range of nontraditional allies – including students, academics, businesspeople, and employees of nonprofits, both Chinese and foreign – to further its intelligence goals. During the Cold War, the CIA helped fund the literary magazine Encounter co-founded by the influential neoconservative Irving Kristol. Edward Snowden’s 2013 revelations showed some of the links between the National Security Agency and American companies like Verizon. In China, these links are the rule, not the exception.

Beijing still conducts normal espionage and spycraft: infiltrating enemy organisations, hacking into rival governments, and cultivating foreign agents—sometimes by sending them messages on LinkedIn. But it does a whole lot else, too.

In 2018 the Party History Research Center, an important institution that helps drive and reflect the Party’s view on history, published an essay on Zhou’s views on spying. Zhou believed the Party had a ‘remarkably’ different stance toward espionage from that of other countries, because it linked espionage with United Front work. ‘Zhou advocated making many friends, using United Front work to drive intelligence work, and nestling United Front work within intelligence work,’ the essay said. Before running the Chinese government as its premier, Zhou founded the Party’s intelligence unit and built its first espionage cells. Zhou, in other words, was the Party’s first spymaster. And in this Chinese sense of ‘espionage’, Kissinger was Zhou’s most important American asset. In Chinese parlance: a friend.

The annals of spycraft are replete with people who likely had no idea they were being fooled. ‘Any unwitting agent is more effective when left in the belief that they are genuinely holding the moral high ground, not representing an authoritarian intelligence agency,’ Thomas Rid, a professor of security studies at King’s College London, testified to Congress in March 2017. The best agents, in other words, are the ones who don’t know they are agents.

Because of the mismatch between the Party’s expansive view of espionage (that includes what American targets often perceive simply as friendship) and the more constrained Western view, Americans often don’t understand the deal they are taking when they ‘accept’ the friendship. Indeed, few friends have ever expressed any public awareness of what friendship actually means: support not of China but of the Party. The Party expects friends to silence their criticism, so as not to ‘embarrass’ or ‘offend’ China, and to praise and advance the Party’s policies. ‘Being a “friend” of China means you’re politically in tune with the Communist Party,’ said the longtime China scholar Perry Link, ‘whether you know it or not.’

Kissinger is one of the most brilliant thinkers of the twentieth century and has more experience dealing with the Party than any American, alive or dead. Why not just take what he said about China at face value? In other words, why not assume that Kissinger’s words and actions reflect his intellect and experience? To answer that, it’s helpful to quote some of Kissinger’s contemporaries about his character. A man as powerful as Kissinger will always create enemies. But Kissinger incited an astonishing amount of invective, especially from those who worked with him directly. ‘I admire Henry,’ said Richard V. Allen, who served as Ronald Reagan’s first national security adviser. ‘What is troubling about him is why he needs to be so devious and manipulative—he’s so brilliant, he works so hard. He sees connections before everyone else. He could rise just as high if he played straight. But for some reason, he just can’t play straight. He has to manipulate.’ In a January 1989 phone call with the Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, George H. W. Bush thanked him for meeting with Kissinger and said he looked forward to the briefing on the meeting. But ‘they would not necessarily believe everything because this was, after all, Henry Kissinger,’ Bush said, according to a transcript of the meeting.

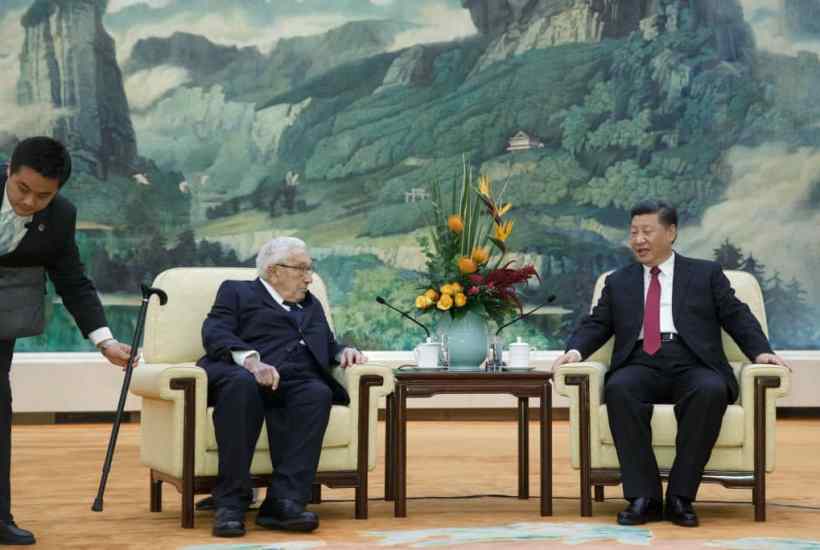

In his decades-long reign as arguably the world’s most famous living statesman, Henry Kissinger has been called many things. Senator John McCain called him the world’s most respected individual. The novelist Joseph Heller called him an ‘odious schlump who made war gladly.’ Xi Jinping calls him an ‘old friend of the Chinese people.’ But the most accurate way to describe Kissinger, from the time he started his consulting company in 1982 to the present, is as an agent of Chinese influence. He may be one of the most brilliant Americans of the twentieth century—and a former intelligence agent himself—but he should have been more vigilant.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in