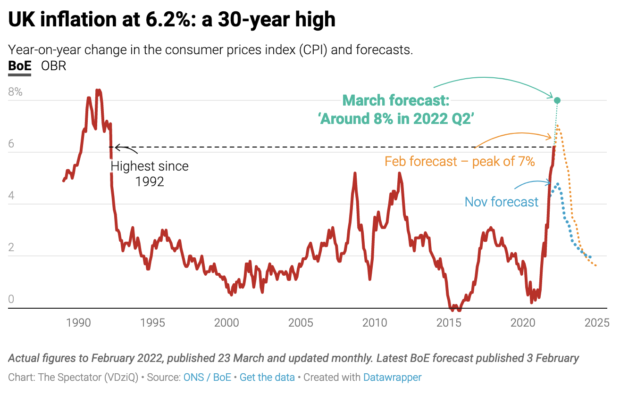

There was a time when a chancellor would have bitten off the hand of a national statistician who offered him an inflation rate of 6.2 per cent. But that takes us back to the days of Denis Healey and the early months of Geoffrey Howe’s time in Number 11. There is little disguising this morning’s grim news, however. The last time the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) was at 6.2 per cent was in March 1992 – although at that time the index was little used as the government’s preferred measure of inflation was then the Retail Prices Index (RPI).

The worst thing about today’s figure is that it doesn’t even yet include the massive uplift in domestic energy prices coming in April as the price cap is lifted by a whacking 54 per cent from £1,277 to £1,971 for an average dual fuel bill. Nor does it yet fully reflect the surge in petrol and diesel prices following the invasion of Ukraine. Today’s figures are for February – we will have to wait a couple of months before the inflation in domestic energy bills feeds through into the CPI.

Remarkably, nor was food one of the main drivers of the increase in inflation this month. The biggest three contributors were recreation and culture, furniture and household goods. That suggests that inflationary forces are spreading quite widely in the economy – although it ought to be pointed out that the rise in prices associated with recreation and culture was mostly reversing a sharp fall this time last year as lockdown forced producers to cut prices.

That said, this no longer feels like a simple case of prices rebounding as the economy recovers – the ‘transitory’ effect which the Bank of England was insisting upon for much of last year. It looks much more like a new era of inflation with a number of factors involved, not all of them connected with either Covid or Russia.

For the past three decades, there were strong deflationary forces as much of our industry was offshored to a lower-cost environment in China and elsewhere in South East Asia. That effect has largely worked its way through now: there is less manufacturing left to be transferred to Asia, and in any case years of rising wages in China and elsewhere have reduced the differential in production costs.

On top of that, the trade war started by Donald Trump has sparked a trend for the repatriation of some manufacturing – a trend exacerbated as companies seek to reduce the length of their supply chains in reaction to the disruption caused by the pandemic.

The one piece of good news – for the Chancellor at least – is that wages are not yet driving inflation. Last week’s labour market figures showed total pay (including bonuses) rising at 4.8 per cent on the year – significantly lower than inflation. For the moment, at least, pay remains fairly constrained, with workers absorbing a fall in living standards. Rishi Sunak cannot count on that lasting, however, especially with a tight labour market.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in