‘For far too long,’ Sir Antony Beevor writes, ‘we have made the mistake of talking about wars as a single entity.’ In Russia: Revolution and Civil War he sets the record straight for the bitter years between 1917 and 1921, revealing the myriad ways in which individual actions constellated and 12 million people perished. This is not a story about winners and losers. As the war correspondent Martha Gellhorn once wrote about every conflict everywhere: ‘There is neither victory nor defeat; there is only catastrophe.’

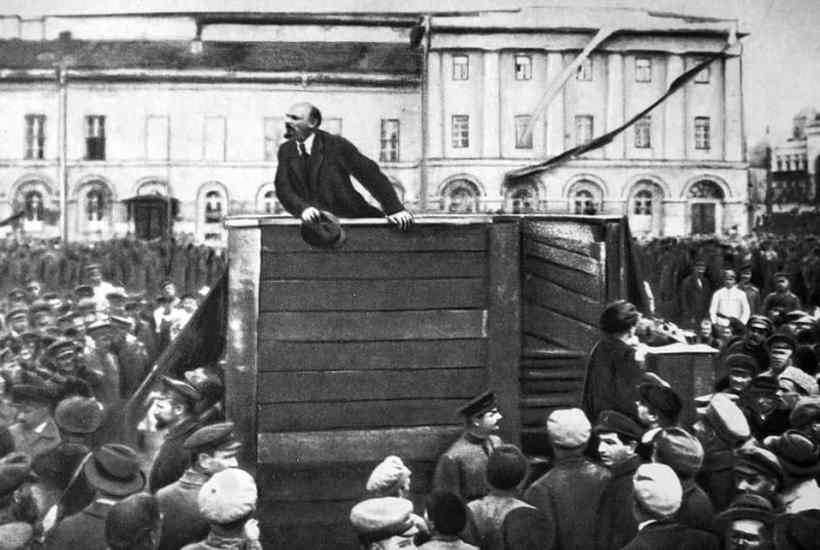

It seems wrong to categorise this book as military history. It is like reading a film. Typhus-bearing lice in hospitals at the front are so abundant that they crunch under nurses’ feet ‘like sugar’. Nadezhda Krupskaya is ‘washing up’ in the squalid Zurich flat when ‘a breathless friend burst in’ bringing Lenin news of the February revolution. In starving Petrograd, ‘through broken panes, the only glimmer came from starlight reflected off the less than pristine snow’. In a rare interlude of calm during the short-lived German protectorate, ‘ox-eyed beauties of Kyiv roller-skate on the city’s rinks with officers’.

Like a cameraman, Beevor twists his lens between the close-up and the wide-angle. On the White Volunteers Ice March during the first Kuban campaign, ‘a bloody tail’ several miles long drags carts heaped with wounded men. Mounted police known as ‘pharaohs’ appear in black capes with red braid and flat astrakhan hats plumed with black feathers. Both Beevor and his research assistant have a novelist’s eye for the telling detail, even though their canvas is half the size of the planet. General Rodola Gajda’s troops, advancing on Kazan, find their boots rotting in spring mud and rain known as rasputitsa. On the train from Switzerland, Lenin, chugging home to free his people from their Tsarist chains, organises a rota for the use of the train’s two lavatories. This kind of detail accumulates to powerful effect.

The field of Russian civil war studies is crowded in many languages, and Beevor, whose books have sold millions of copies, has mined the sources with academic rigour. In this volume he confidently sets out military strategy in all its complexity and confusion, marshalling shifts, tides and patterns as corps, armies, guerrillas, underground cells and loose military alliances on flanks and fronts fragment and consolidate. Sometimes describing events day by day, he charts congresses, offensives and counter-offensives, insurrections, hungry winters, real or invented bourgeois sabotage (Bolsheviks called the dispossessed upper and middle classes ‘former people’) and the ‘whole imbroglio of misunderstandings’ as strategies alter and alliances weaken.

The consequences of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty signed on 3 March 1918 dominate the middle third of the narrative. The first world war ends halfway through the book, but in Russia ‘peace never stood a chance’. As late as November 1920 hope flared for the Whites, though. Most revolts towards the end were not political – peasants were angry that communist food detachments seized their grain and animals. It was a terrible winter in the Caucasus too: birds froze and fell from the air.

It does not matter that the reader struggles to follow whether the 14th Division on the left flank of the 9th Army ever did meet up with the 10th Army based in Tsaritsyn: the story steams through the fog of war. Along the way we read of the baleful atamansh-china, the Cossack atamans’ rule of terror on the Quiet Don; mass rape everywhere; and Jewish pogroms of unspeakable horror sustained at least in part by ‘the vengeance myth of the extreme right that every Jew must be a Bolshevik’.

Like the first and second world wars, this one crosses continents. The action switches back and forth between the Crimea, the north-western Estonian front, western Siberia and the Polish hinterland. Ukraine features prominently – Kadets called it ‘Little Russia’. In what by mid-1918 ‘was fast becoming an international civil war’ Beevor’s cast is multitudinous, multinational and multi-ethnic. Czechs duke it out along the Trans-Siberian railway, many wearing high sheepskin papakhas; Armenian women encircle the Baku peninsula side by side in trenches with Tatars; and Kalmyks bring camels, whose humps flop to one side when they starve. Japanese troops at Khabarovsk have their yoshiwara (like the later ‘comfort women’), each soldier allocated an allowance of tickets to use them (American intelligence estimates that the Japanese at one point had 85,000 men and 14,550 horses in Siberia). Churchill pops up a lot, though I found the role of Britain, as Lloyd George and Churchill disagree over strategy, the least interesting thread in the second half of the book.

Beevor presents dense data in a resolutely narrative style that is fluent and agreeable. The second chapter opens: ‘The drift towards revolution was clear to all except the wilfully blind’, and the 24th ends: ‘The white ensign had been flown for the last time on the inland sea.’ Above all, and crucially, he lets others speak. Directly quoted individual voices are the yeast that allow history to rise. They include Roman von Ungern- Sternberg, a baron ‘with moustaches shaped like a water buffalo’s horns’, Stalin’s Polish ally Feliks Dzerzhinsky, who has ‘a pale El Greco face and a wizard’s beard’, and the obese General Vladimir Mai-Maevsky, who resembles ‘a dissolute circus manager’. The book is a fugue in many tongues.

Of slaughter and torture there is no end and the action is close to genocidal. In Siberia, both sides strung up men and women on roadside trees and wolves ate their feet. An old colonel is roasted alive in the furnace of a locomotive. Victims were bound with barbed wire and pushed through ice holes or were skinned alive. In Kyiv, the Reds attached a short length of pipe to a prisoner’s stomach, fastened it securely and inserted a rat, setting fire to the other end so the rodent had to eat its way out. The Whites do not emerge with any credit or dignity, but Beevor, in his final line, makes this judgment: ‘All too often the Whites represented the worst examples of humanity. For ruthless inhumanity, however, the Bolsheviks were unbeatable.’

Not a single entity then. War is what individuals do or have done to them in events that roll inexorably on, like a snowball or a Greek tragedy. Beevor is actually a second world war specialist (in 1925 the previously mentioned Tsaritsyn became Stalingrad, the subject of his monster bestseller) and he comments occasionally on the ways events foreshadow (‘give a foretaste,’ he calls it) of horrors to come. Together with a strong opening, setting the events of 1917 in their historical place, these glances to the future lend the story a robust sense of context. Otherwise, the book avoids the longue durée approach.

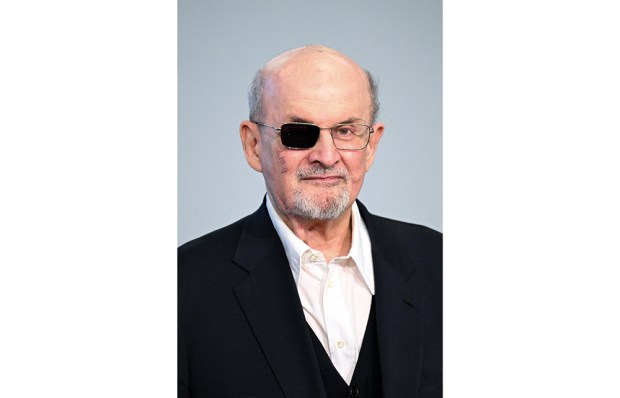

When the non-academic reader flags, up pops Ivan Bunin or another literary titan to add their voices to the fugue. Vladimir Nabokov’s father’s valet packed caviar sandwiches for the exile journey. As for the incomparable Bunin, after Odessa changed hands yet again, he wrote: ‘Even the sea smells of rusty iron now.’ Konstantin Paustovsky, currently enjoying renewed popularity in the English-speaking world, has a good showing, as does Nadezhda Lokhvitskaya, known as Teffi, the better writer of the two (‘Lenin simply battered away with a blunt instrument at the darkest corner of people’s souls.’)

Early on, Beevor says that the provisional government prime minister, Prince Georgy Lvov, ‘blindly believed in the essential goodness of the people (what Maxim Gorky called “Karamazovian sentimentalism”)’. One cannot read this gruelling volume with any optimism. It makes one feel that the sooner humankind goes extinct by its own hand, the better. The Earth can carry on without us, for we are a nasty lot.

The author is so accomplished that occasional infelicities come as a relief. It is pleasing when days are numbered, word spreads like wildfire, silence is stony and even Vladimir Ilyich does not pull his punches. Beevor might be brilliant, and might have mastered the accessible, vivid style to which all modern historians aspire and, worst of all, have sold those beastly millions, but a cliché beats him from time to time. I will therefore end with a cliché myself. The book is a masterpiece.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in