Something momentous is building in the Philippines. Thirty-six years after the kleptocratic despot, Ferdinand Marcos, fled into exile with his family and 300 crates of loot aboard a US airforce transport plane, his only son, Ferdinand Marcos Junior is on course to win Monday’s presidential election. He’s known by his nickname ‘Bongbong’ and is not so junior these days. Now 64, he proudly praises the ‘political genius’ of his father and boldly promises that with another Marcos ensconced in Malacañang presidential palace, the Philippines ‘will rise again.’ The latest opinion polls put him 30 points clear of his liberal rival.

It may seem like a remarkable feat of political resurrection considering how tarnished the Marcos brand is. But the disgraced dictator has been ably rehabilitated over the past six years by the outgoing president, Rodrigo Duterte. Much as Duterte admires the former tyrant, this has not been simply been an act of altruism. It has been a politician covering his own bases.

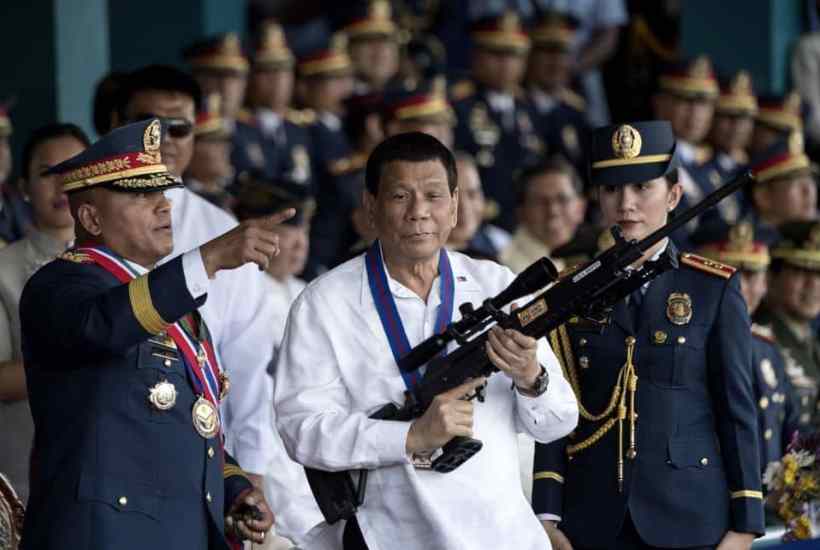

They call him ‘Duterte Harry’ – after Clint Eastwood’s shoot-first-ask-questions-later vigilante cop ‘Dirty’ Harry Callahan. Duterte, the former mayor of a city in the south, had swaggered into the Philippine political arena in May 2016, threatening to blow punks’ heads clean off. He posed as ‘the law and order candidate,’ promising to sort things out, just as he had as mayor. He promised to kill so many drug addicts and criminals that the fish in Manila Bay would grow fat feasting on their bodies.

Duterte possessed a gangster charm and soon had the electorate swooning. In a country more staunchly Catholic than the Vatican, he called Pope Francis a ‘son of a whore’ and got away with it. He got away with murder too. Once in power he unleashed a Narcos-style bloodbath on the country’s drug dealers, complete with death squads. If the Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court is right, between 12,000 and 30,000 civilians were killed within Duterte’s first three years in office during this war on drugs. In the first six months alone, vigilante killers – alleged by the ICC Chief Prosecutor to have mostly been on and off-duty police – actually killed three times as many Filipinos as had died during Ferdinand Marcos’s era of martial law during the 1970s and 80s.

From early in his presidency, in rambling late-night addresses, Duterte eulogised Ferdinand Marcos Senior and set about the task of rehabilitating his reputation. He described him as the best president the Philippines ever had. To the surviving victims of the Marcos regime – when 3,000 were killed and thousands more jailed and tortured – this felt like an assault on the country’s collective memory. But President Duterte said it was time to bury the past. Literally. He approved the furtive reinterment of Marcos’s remains in the national Cemetery of Heroes. Bongbong Marcos and his sister, Imee – then governor of the family’s home province of Ilocos Norte – were then hand-picked to accompany Duterte on foreign trips, most notably his first state visit to China. Within a year, a new 12-peso stamp was issued bearing the dead despot’s smiling face. Many Filipinos were aghast. But this, as it turned out, was just the start of Duterte’s whitewashing campaign.

Duterte’s own legacy will be defined by the violence which accompanied his rule. But those who’ve watched and documented the country’s slide back into autocracy say a more enduring feature has been his casual normalisation of authoritarianism. Duterte’s period in office has been accompanied by the erosion of human rights, hobbling of the judiciary, the jailing of opponents, the hounding of journalists and the weaponising of the internet.

Five years ago, I was writing a book about Duterte when I interviewed the award-winning Filipino novelist Miguel Syjuco, who, saw it all coming back then. In light of what’s happening now, what he said was prescient. ‘History is repeating itself. Even the names of the past are back,’ he said.

‘It’s dangerous not just because it’s happening but because we are letting it happen. Duterte represents what happens when you allow democracy to be perverted. What scares me most is what our democratic institutions will look like at the end of this. Thirty years is an entire generation over which the people of the Philippines have forgotten the lessons of dictatorship.’

Half the archipelago’s 110 million population hadn’t actually been born back in 1986, when the Marcos family was forced into exile in disgrace. The Marcos left behind a brutalised, angry country whose coffers they’d plundered. The Philippine economy had nose-dived into debt. Inflation had surged to more than 50 per cent, forcing devaluation of the peso. For older Filipinos, this is seared into their memories. It’s what fuelled the People Power revolution which led to democracy in the Philippines. But now, 36 years on, the promises of that half-forgotten revolution have been squandered and history re-written by the victors.

On the election trail these past few months, the dead dictator’s son has been brazenly recasting the dark years under martial law as ‘a golden era’ of prosperity, stability and discipline. Meanwhile, to the disbelief of the surviving victims of repression, Ferdinand Marcos Junior has even questioned whether widespread human rights abuses carried out by his father happened at all.

If the opinion polls are right, it now seems the majority of the country’s 67.5 million voters are prepared to give him the benefit of the doubt. If he wins, Ferdinand Marcos Junior will find himself in charge of government agencies still seeking to recover the billions his family plundered. Criminal and civil cases trying to claw back his family’s unexplained wealth, together with their unpaid tax bills, are unlikely to go anywhere.

Call it nostalgia for dictatorship, but East Asia’s oldest democracy, it seems, does love a strongman. Duterte is leaving office next month with an approval rating of 67 per cent. But as he does, the country’s apparent preference for authoritarian leaders may prove very handy for him. The ICC investigation into his war on drugs has been temporarily suspended because the government claims the judiciary has begun its own investigations into the killings.

It’s not likely that a new Marcos regime will allow meaningful investigations into Duterte. And given that the vice-presidential running mate of Bongbong Marcos is none other than Duterte’s daughter, Sara, the outgoing president has probably calculated he won’t be shipped off to the Hague either. Duterte is a wily politician. There are many who wonder whether this might just have been his game plan all along.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in