I have just posted a score of 1,625,000 on Bubbleshooter, my best yet. Bubbleshooter is a game where you fire different coloured bubbles at other different coloured bubbles in order, in the end, to make all the different coloured bubbles disappear. It is an elderly game, in its uplifting nihilism, and almost certainly dates me precisely. My latest attempt took slightly over one hour. I had intended to spend the afternoon finishing the book I’ve been reading, but having logged in on my laptop became momentarily and later endlessly distracted.

First I did the Times and Telegraphcryptic and ‘toughie’ crosswords, then I did Wordle, of course – identifying the word ‘album’ in three goes, which the website assured me was ‘impressive’. Now, I thought to myself, time to get down to the book. I’ll make a cup of tea and maybe relax first by seeing what idiocies have been posted on Facebook in the past 24 hours. Then I remembered Bubbleshooter and thought to myself – well, why not? It will put me in a good frame of mind.

This is the sort of thing I tell myself. I start each working day with the cryptic crosswords because, I tell myself, it gets my brain in shape quickly. I stop halfway through an article to play Bubbleshooter, or do a cryptogram, because it clears my mind and helps me to relax. These are cogent explanations: a practical benefit accrues as a consequence of me zapping green bubbles with other green bubbles.

It is not the same, then, as all the other people who waste their time online – they simply have sad and empty lives. Not me. Almost everything I do on the laptop, except for work, bestows upon me cheering benedictions, all testifying to my brilliance or adorability. The upticks or hearts for the platitudinous drivel I post on Facebook, the commendations when I do well at a puzzle or a game. Is it this which persuades me to waste a substantial chunk of my life online – that I am sufficiently insecure and needy to require these constant injunctions from, largely, machines as to my own brilliance? Could well be. Or is it something else?

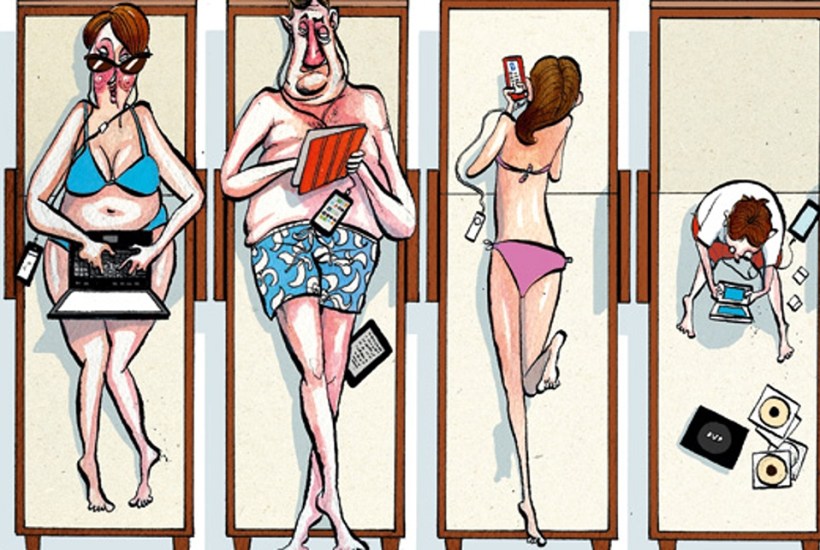

Now it is four o’clock and the book is still sitting on my desk waiting to be opened. It is called Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention, by the excellent journalist Johann Hari, and it is about the woeful amount of time we spend on moronic online pursuits to the degree that we are no longer able to concentrate. The compulsion which drags us to the inane and easy and our consequent in-ability to focus or to engage with complexity and, in extreme cases, the real world.

An irony, then. This may be one of the most important books of the past few years, and yet given the choice – and we are all given the choice – I would rather smash those bubbles than read the concluding chapter. It is not that Hari’s book is an onerous read – he is a supremely gifted and very likeable writer. But all books require of the reader self-discipline when compared with the intellectual tax levied by the likes of Bubbleshooter, or TikTok.

Hari details, with copious evidence, what this is doing to our abilities to concentrate, think and in the end engage with other people: take in our surroundings, experience the real world. It is very well researched and a little depressing although I am relieved to know that I am not quite as far gone as almost the entirety of Generation Z or indeed the writer himself (who is perhaps 20 years my junior). At least I am not a slave to my phone – but maybe only because I am not sufficiently adept at using it to be so. Hari writes about his benighted godson, Adam: ‘His attention, which had been deteriorating for some time, was now shattered. He was on the phone almost every waking hour, seeing the world mainly through TikTok, a new app which made Snapchat look like a Henry James novel.’

Hari insists that this condition in which we find ourselves is not simply a consequence of individual lack of self-discipline. He blames – probably rightly – the machinations of Big Tech, as well as three generations of young people who have not been allowed the independence in the real world which we had as children. Being a lefty, he also blames bad diet, capitalism and air-borne pollution, and while I am (inherently)more dubious about all this, he presents some fairly compelling evidence.

I was thinking about Johann’s book while watching a documentary called Britain’s Strictest Headmistress on ITV. This was about Michaela, the free school in Wembley founded by the wholly admirable teacher Katharine Birbalsingh and which gets extraordinarily wonderful exam results from its intake of largely very poor, disadvantaged kids. I have to say I found the constant chanting, the enforced silences and various mantras a little, y’know, Third Reichy. But perhaps that is what is needed to turn out bright, well-read, alert and polite young people – a bit of rigour, a bit of the spare-the-rod-and-spoil-the-child mindset. It was certainly pleasing to see the teachers acting as adults and enforcing discipline, rather than trying to be ‘mates’ with their tutees.

It is difficult to think of two individuals politically further apart than Johann Hari and Katharine Birbalsingh – and indeed, Johann’s prescription for our education system is to scrap exams and let the children run free and wild in the hope they’ll learn sooner or later. I’m not so sure. And yet they agree on one thing, these polar opposites. At the Michaela school, no phones are allowed. They are recognised as toxic – a poison which saps the concentration – and so they are confiscated. Sooner or later I suspect the rest of us will start to… what’s the phrase?… pay a little more attention to the damage we have invited upon ourselves.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in