For the first time ever, the number of UK job vacancies – now almost 1.3 million – has overtaken the unemployment count. Normally, this would lead to people in work feeling much better off, and lead to pay hikes and bonuses as employers compete to recruit and retain employees. But in fact, regular pay in real terms (that is, after inflation and before bonuses) is down 1.2 per cent – fuelling the cost-of-living crisis that is now the central fact of British politics. What’s going on?

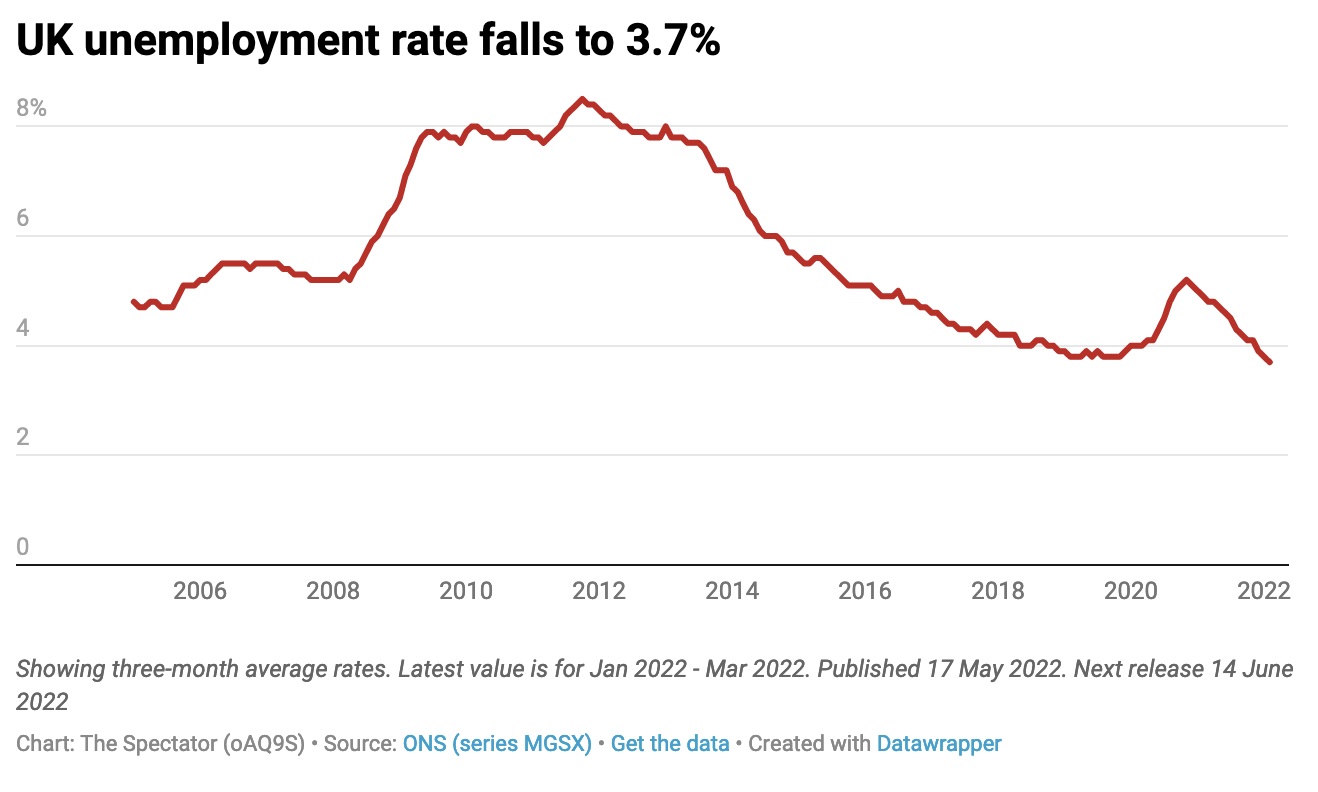

In short, today’s ONS labour market overview is yet another example of how inflation can ruin otherwise good news. Total salaries are up 7 per cent and unemployment fell to 3.7 per cent in Q1 (a record low not seen since the mid 1970s). This is yet another vindication of the furlough scheme, and marks another month in which the dreaded ‘stagflation’ has been kept at bay (rising unemployment is the final ingredient of ‘stagflation’, on top of lacklustre growth and high inflation – both of which the UK is already experiencing).

Yet people are still feeling poorer, as even substantial wage increases aren’t covering the cost of rising bills. And with job vacancies as high as they are, the labour market is getting even tighter, creating further inflationary pressure and risking wage spirals.

This was a big theme in yesterday’s Treasury Select Committee hearing, which quizzed the Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey and members of the Monetary Policy Committee. There was a sense that the high number of job vacancies could be sustainable as long as there is a strong contingency of people looking for work.

But the inactivity rate (those neither in work or seeking work) hit a five-year high of 21.4 per cent. Whatever is driving this rate up (potential factors include more people looking after their family or those who are temporarily sick) is depriving the economy of necessary workers. The concern, as the unemployment rate falls further, is that there aren’t enough workers to eventually fill these roles, leading to a long-term imbalance between consumer demand and the services companies can offer.

This can lead to wage spirals, too. Annual earnings growth has already risen from 5.6 per cent in the three months to February to 7.0 per cent in March. Granted, the main driver of the rise was bonuses; but as was pointed out in yesterday’s select committee hearing, it isn’t just the financial sector handing out substantial bonuses anymore. The panel cited reports of companies such as EasyJet offering £1,000 to cabin crew in a bid to retain staff.

It’s difficult for the Bank to rail against higher wages – especially when real pay is down and workers’ purchasing power falls well behind the inflation rate. Bailey reiterated again yesterday his call for ‘reflection’, especially for ‘high earners’, when requesting a pay raise, as pay hikes across the board are bound to lead to higher prices, as can be seen in the United States now.

As people look to apportion blame for our increasingly limited workforce, the tough truth remains that it’s nearly impossible to separate the effects of pandemic lockdowns, which caused a mass exodus of workers back to their home countries, and changes to immigration rules under Brexit, which are preventing lower-wage workers abroad from entering the UK labour market. As Bailey mentioned yesterday, both are playing a role in our current labour market predicament.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in