As Boris Johnson tries to limit pay rises to bring down inflation, ministers have no explanation for why planned rises in the state pension and benefits would be less inflationary than increasing teachers’ and nurses’ pay. The government is attempting to limit public sector pay to 3 per cent, while allowing pensions and benefits to rise to around 10 per cent.

This is not to argue against protecting the poorest through the standard indexation of pensions and benefits. But it is to say that Mr Johnson’s pay policy is confusing. And he cannot pretend there is no pay policy. Even refusing to engage directly in pay talks with rail workers – despite owning the network and funding services – is a policy.

Johnson’s mantra is that incomes have to be suppressed to bring down inflation. So the question he needs to answer is why he thinks some income rises are toxic and inflationary and others are benign and acceptable. This isn’t just an economic question.

For his party, it is also the difference between political life and death. A swing Tory voter who, for example, earns just above the eligibility threshold for universal credit, and will therefore see their living standards savaged, will think twice before rewarding Mr Johnson at the ballot box. There are two other points.

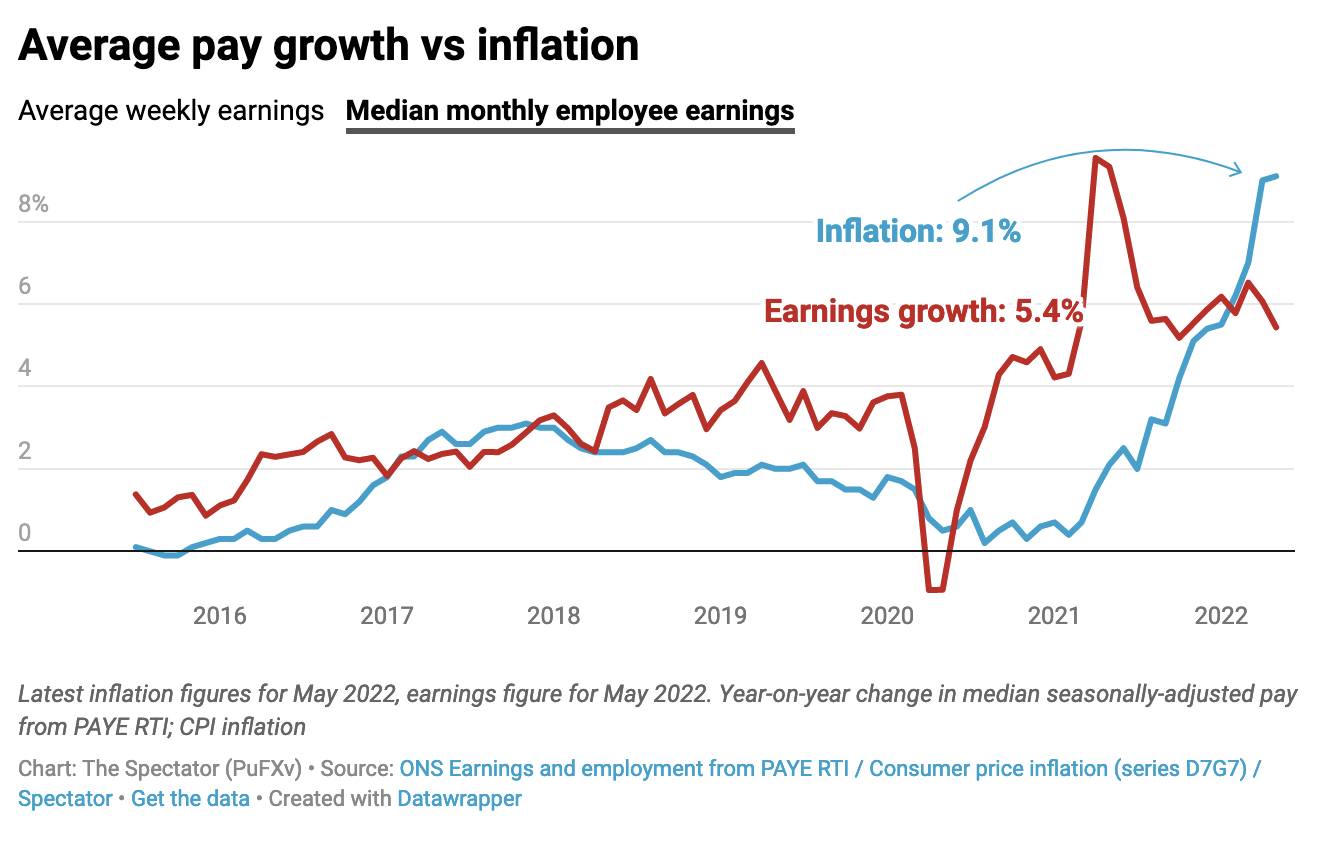

First, the government is the biggest and most powerful employer in the country. The overriding consideration – in Mr Johnson’s own words – is that inflation must be crushed by bearing down on pay rises. But why is it fair that public servants should take the strain in bearing down on inflation when pay rises in the economy as a whole are currently averaging 6.8 per cent (according to official figures)? Apart from anything else, the public sector employs just 17 per cent of all workers in the UK, so squeezing their pay alone won’t eliminate core inflation.

Second, trade unions are much less powerful than they were in the 1970s and even less powerful than they were a few years ago – in 2016 David Cameron made it much harder for teachers, nurses, rail workers and other important public service workers to go on strike. On Mr Cameron’s orders, the threshold for a successful strike vote was changed such that at least half of eligible union members had to vote and four-fifths of that 50% had to be in favour of the vote. This was thought to be a high bar, given normal apathy among union members. It was an attempt by a Tory PM to make sure that no strike could be called except when there was a legitimate grievance.

The thresholds were beaten by a country mile in the RMT strike ballot. Yet the rhetoric of Mr Johnson and his ministers is that rail workers can’t possibly have a fair claim and they are simply holding the country to ransom. This may be effective short-term politics, though opinion polls show voters are fairly evenly divided on whether they support or oppose the strikers. But the risk for the government is that he is encouraging workers to become more militant, not less – because if workers are denigrated as vandals even when they vote in overwhelming numbers to strike, what is in it for them to be more constructive in negotiations and less aggressive?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in