To nobody’s surprise, the Bank of England has hiked its base rate, and, equally unsurprisingly, it has chosen to do so by a relatively modest 0.25 per cent, bringing rates to 1.25 per cent. In 25 years of its existence, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) has never raised rates by more than 0.25 per cent at a time. That stands in contrast to the Fed’s decision to raise rates by 0.75 per cent on Wednesday.

If the modesty of the rise was supposed to calm markets, however, it doesn’t seem to have worked. The FTSE100, already down nearly 2 per cent on the day, plunged further on the announcement. The greater worry now must be whether the Bank, having failed completely to see the inflationary surge coming last year, is now falling even further behind the curve in trying to tackle it.

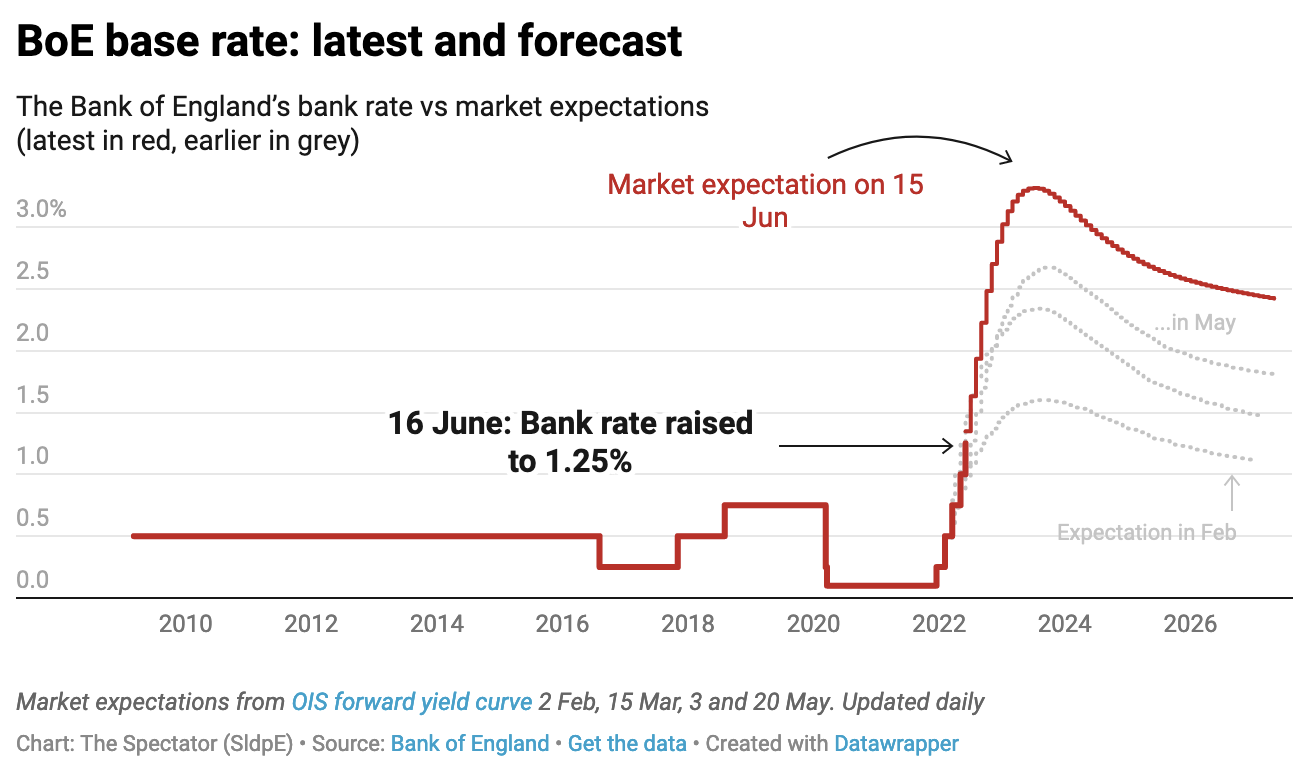

How high could they go? As you can see from the graph, back in February markets expected rates to peak at 1.5 per cent. Now they foresee them reaching 3.5 per cent. But here is a statistic that anyone under the age of 50 will find shocking, even incomprehensible. The last time that the Retail Prices Index (RPI) was at the level it is now – 11 per cent – the Bank of England’s base rate was 13.8 per cent.

That gives a foretaste of what we might get to experience in the coming years if inflation does not fall quickly. Chancellors of the Exchequer (who set rates before Gordon Brown made the Bank of England independent in 1997) did not start out this way – in a bout of inflation in 1952, when the RPI also topped 11 per cent, the Bank of England’s base rate never got above 4 per cent. But as inflation became established in the system, with rising prices feeding into higher wages which in turn feed into even higher prices, ever more forceful measures were needed – hence the harsh monetarist policies which had to be employed in the early 1980s.

Could homebuyers cope if mortgage rates were to be jacked up to over 10 per cent? It is certain that it would lead to mass repossessions – although thanks to low rates of home-buying among young people in recent years we have fewer heavily-mortgaged properties than we did in the past. MPC members might be reluctant to employ drastic rises in interest rates to tackle inflation, but it has to be said that their sole remit is to keep the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) at or as close to 2 per cent as possible. They are not under instruction to take the pain being inflicted on homebuyers into account – other than in the sense that mass repossessions would very likely crash the economy and could, possibly (although possibly not), bring inflation to undershoot its target.

What is most frightening about the current bout of inflation is the speed at which it has happened and the failure of the Bank of England – or many others – to foresee it. Indeed, for much of the past decade policymakers were minded to worry themselves more about the threat of deflation – something which in the event never happened save for two months in 2015 when CPI dipped down to minus 0.1 per cent.

For years, inflation has gone off the radar. We became used to the idea that prices were pretty stable, and that the MPC had a reasonable idea of what was going on. We are entering a very different era of instability – and unpredictability. Even if inflation does fall back later in the year the conceit of a wise MPC tweaking here and there to keep inflation on a steady course has been dashed, perhaps for good.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in