Julia Blackburn’s Dreaming the Karoo is the diary of a very bad year: from March 2020, when a research trip to South Africa was cut short by the sudden emergence of Covid, to March last year. Blackburn had gone to Cape Town, and then into the dry interior, the Karoo, to explore the lost world she had found in an obscure volume that she had once chanced upon in the London Library.

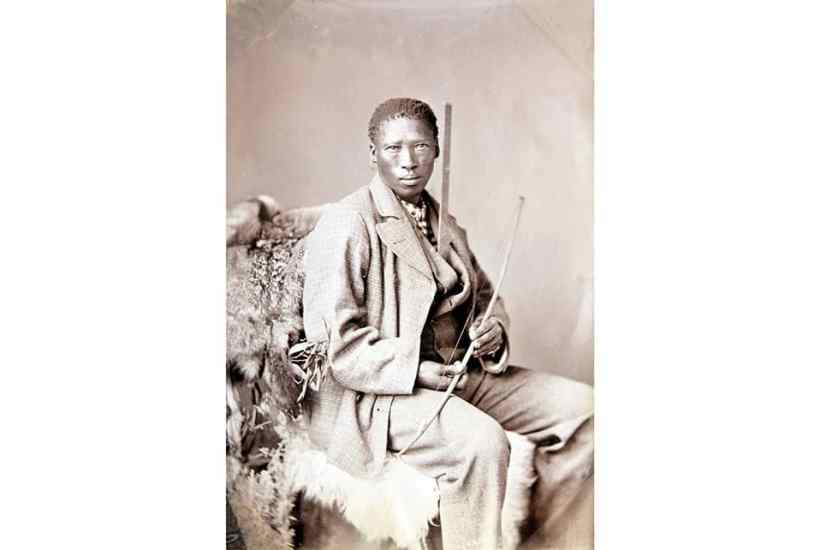

Specimens of Bushman Folklore, by the linguists Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd, published in 1911, contains the texts – life stories, origin myths, tales about animals, accounts of murders of women and children by the encroaching colonists – given by many of the /Xam, a Bushman group of hunter-gatherers. These informants were captives, hundreds of miles from their homes. Blackburn writes:

Nearly all of the prisoners held at the Breakwater Jail were being punished for stealing or killing or eating a sheep, and many more were murdered at the place where the crime was said to have been committed.

As death and terror spread across the globe early last year, Blackburn bolted home to England. There she bunkered down in isolation, as all of us did who were lucky enough to make it through closing borders. Back in her studio she turned her attention to the stories that the /Xam had told a century and half earlier. Blackburn had lived with the /Xam and their stories that ‘may float into my ear’ for decades. She had first borrowed Specimens of Bushman Folklorein 1974, and had renewed it repeatedly. To write this book she reread it ‘over and over again, until some of the texts began to merge with my own memories and experiences’.

She found the Covid-ruptured world of her present reflected in those texts from another time and place. She shaped the material she had, trying to understand the lives of those long-dead people. From the loneliness of that strange fever dream time of the pandemic, when the membrane between the past and the present became porous, this remarkable book emerged. Blackburn’s account merges with the distinct voices of storytellers such as //Kabbo, /A!kunta, //Hankass’o, Dia!kwain and Tamme.

The exquisite and often strange vignettes of an ancient hunter-gatherer lifestyle, recorded meticulously by Lloyd, stand in stark contrast to the brutality meted out to the Bushmen by land-hungry Boer and British colonists. Blackburn writes:

To a people like the /Xam we must have appeared as creatures that lacked something crucial in our nature; creatures who did not seem to understand pity… We apparently had no sense of the transgression of shooting men, women and children who could not defend themselves; the transgression of shooting thousands of migrating springbok; the transgression of leaving baby elephants beside the bodies of their mothers because of a growing demand for ivory… It seemed we also had no pity for the land itself, but were willing to destroy it completely. And now the pandemic moves among us and we do not know what to do with our fear and our sense of culpability in the face of it; how to save ourselves in a world we thought we owned, to do with as we wished.

During her March 2021 trip through the Karoo, Blackburn turns her discerning eye to a silent landscape that has been ruthlessly emptied of its teeming wildlife. She writes that ‘nothing had prepared me for the destruction of the animals and the landscape that held them’. The veld is silent. All the game was replaced with sheep – ‘starvation’s food’ as the hunter-gatherer //Kabbo called them.

She retraces what she can of the tracks left behind in the accounts given by //Kabbo, Dia!kwain and /A!kunta, which were full of the violence of colonial expansion – the slaughter of the Bushmen and the mass killing of the game. In 1882, 120,000 elephants were killed, on which they depended: ‘It was for the sake of the sheep that everything else had to be removed, not only the predators, but also the eaters of the sparse food of the veld.’

Blackburn abandoned her original intention of turning the /Xam texts into found poetry, as has been done twice before by the South African poets Stephen Watson and Antjie Krog. Instead, they become part of her narrative and it is as if these long-dead people are speaking for her. The bewilderment, pain, anger and wisdom of the /Xam in the face of extinction provided Blackburn with a language that could contain her own fears about the precariousness of human life in the face of forces beyond the control of the politically insignificant. The /Xam storytellers evoke the beauty and occasional abundance of a vanishing natural world and detail family relationships and the grief for lost loved ones.

This is a delicate project: to take the words of the /Xam without stealing again from people forced off their land, and to weave those stories into her own words of loss, wonder and dislocation, but Blackburn pulls it off. Her observations of the desolation of a Karoo, stripped of all wild life and of South Africa’s violent history that endures in the present, are piercingly exact, as is her evocation of the ghostly, frightening loneliness of the pandemic. Her writing of history and memory – both personal and public – is so deft as to seem effortless. This elliptical and bewitching book is a delight.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in