‘Truss’s campaign to be Britain’s next prime minister,’ wrote one political commentator this week, ‘seems to have unstoppable momentum. She has won the backing of heavyweights Tom Tugendhat, Brandon Lewis and the Chancellor, Nadhim Zahawi.’ Across a range of commentary you will see that word ‘momentum’ used in this sense in the weeks ahead. I am uncomfortable about what drives it.

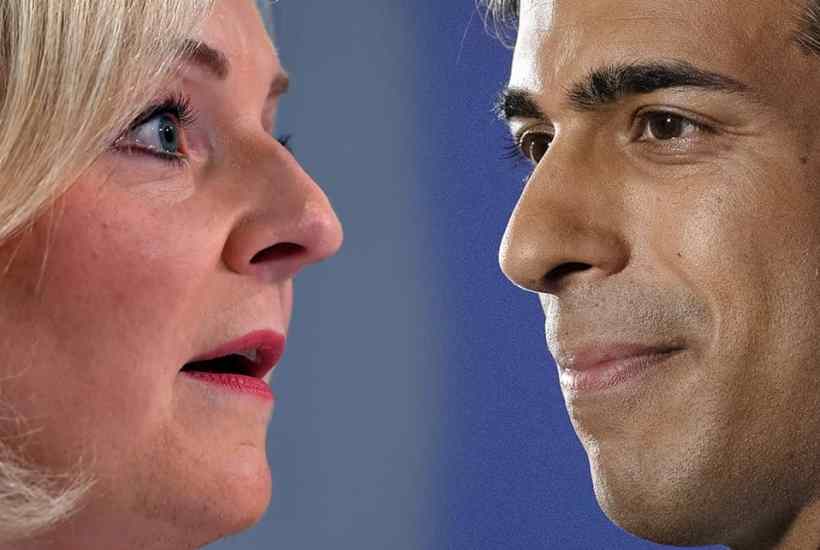

You may realise that if I were still a member of the Conservative party I would be voting for Rishi Sunak this month. Of the two candidates he is plainly less likely to win. So you may well think my discomfort with the procedure by which Liz Truss has been pulling ahead is sour grapes. Perhaps it is – we are seldom the best judges of our own motives. But hear me out.

Assuming (if we should) that balloting the members of the contestants’ political party is the best way to choose a prime minister, I still think the process the Conservatives have adopted is defective in at least two respects. Firstly, it does not tell us the balance of the parliamentary party’s judgment as between the two finalists whose names are put to the members. Secondly, it allows the MPs to vote secretly, hide their support until it becomes apparent who is likely to win, then advise the national membership how to vote.

I have moderated many local Conservative selection meetings for a prospective parliamentary candidate. Up to four shortlistees are presented to members attending. The voting system proceeds in stages. First they can vote for any of these finalists. The candidate receiving the fewest votes then drops out, and the process is repeated until only two remain. These two names are put to the meeting, and somebody wins an absolute majority.

The parliamentary part of the process for selecting a leader mirrors this arrangement except in one respect: it finally produces two names, not one. Nobody therefore knows the level of support each would have received from the parliamentary party in a run-off between the two of them. The person who received most votes in the ballot reducing the candidates from three to two might have not have been the MPs’ favourite among those two.

In the fifth and final round of the selection last month, Sunak received 137 votes, Truss 113 and Penny Mordaunt 105. Imagine a sixth round had been held. If all Mordaunt’s former supporters had switched to Truss, the result would have been Truss 218 and Sunak 137. If Sunak had been the preference of all Mordaunt’s supporters, the result would have been Sunak 242 and Truss 113.

Depending how Mordaunt’s former supporters were distributed (indeed, are distributed, because they exist and each will have their preference) you will come up with results ranging from ‘Sunak is Tory MPs’ runaway favourite’ to ‘Truss clear favourite of Tory MPs’. You and I, of course, have no idea how the Mordauntites’ vote, deprived of Mordaunt, would have broken, and the result of that hypothetical sixth round might be uninteresting. But it might be very interesting indeed. And we will never know. More to the point, the wider Tory membership, who must now decide, will never know either.

Should they? In my view, Tory MPs’ opinion on who should lead them is either critical or it is not. The party has decided it’s critical, hence the process instituted. To decide it’s critical right up until the point when we might learn which of two candidates the MPs prefer, whereupon a curtain is drawn on their opinion, is eccentric.

The anomaly is not, however, accidental. The rule-makers’ wish was to avoid the embarrassment of the national membership being seen to reverse the order of their MPs’ preference. But that doesn’t mean the membership may not do so. They may do so in this case. It’s just that they won’t know they’re doing it. Were I a member I would want to know before I made my own decision.

Instead, however, the expressed opinions of those in the parliamentary party are now influencing the national membership’s opinions by a different route. One by one, senior Tory MPs are going public with declarations of support for one candidate or another. Almost all of them, with brave and honourable exceptions such as Damian Green and Julian Smith, seem to be recommending Truss. Thus the impression of a gathering ‘momentum’, with which I started this column. Frontbencher after frontbencher is effectively urging party members to vote for her.

I’m genuinely unsure to what extent the national membership is aware that these endorsements may in fact be job applications for a position in a Prime Minister Truss’s ministerial ranks. Her newly announced fans include Zahawi, Tugendhat, Lewis, Ben Wallace, Kwasi Kwarteng, Simon Clarke… some of these will be natural Truss supporters; but all of them?

Having no window into any of these souls, we cannot know what has motivated each. There may have been some honest conversions. But in politics the perception that a particular candidate is likely to win will be part of the calculations of some who jump on their bandwagon, and may determine their choice. Let me put it like this: imagine Sunak were the runaway favourite to win. Would all these people be declaring now for Truss? Product endorsement by opinion-leaders with an undeclared interest in sales is outlawed in other contexts.

And what, finally, is driving this – what, if not opinion polls claiming to know the mind of the party membership? That’s what started the Truss bandwagon. Polling a membership whose list is secret, and many of whom are hard to access by modern means, is a tricky business. It is possible the real balance of activists’ opinions was more even.

For what, in the end, are we looking at? Pollsters telling job-hungry MPs who’s likely to win; then job-hungry MPs (most of whom had at first hidden their preferences) announcing whom they recommend to party members. These polls had better be right, or there are some big questions to be asked.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in