Listen

Whether or not Ukip wins, this month’s European election campaign has belonged to one politician alone: Nigel Farage. Single-handedly he has brought these otherwise moribund elections to life. Single-handedly he has restored passion, genuine debate and meaning to politics. Single-handedly he has reinvented British democracy.

This is a superlative achievement, and Mr Farage deserves to be celebrated. Instead strenuous attempts have been made to turn him into a figure of odium and contempt. Farage has twice been physically assaulted, once when attacked with eggs whilst campaigning in Nottingham, once when struck on the head by a placard-bearing protester in Margate.

He has been labelled a racist and a fascist. There have been comparisons with Hitler. He has endured by far the most hostile press and media coverage of any mainstream politician in living memory — far more brutal than anything encountered by Neil Kinnock in 1987 and 1992.

Besides the smears, Mr Farage has endured intrusion into his private life. In the European parliament, Nikki Sinclaire used parliamentary privilege to accuse Mr Farage of having an affair with his press officer. This unproven allegation, denied by both parties, was reported at substantial length that night on BBC News at Ten.

The BBC coverage of Mr Farage has been hostile, while Channel 4 News has treated Mr Farage with contempt. Several newspapers, above all the Times, have run vendettas or smear campaigns. The Sun pictured Mr Farage as half devil, in an echo of the notorious ‘demon eyes’ attack by the Conservatives on Tony Blair. Mr Farage has carried on regardless, in a praiseworthy display of moral and physical courage.

This deep, visceral media and political contempt should be put into context. Nigel Farage is a subversive who has reintroduced the vanished concept of political opposition into British politics.

When he emerged as a force ten years ago, Britain was governed by a cross-party conspiracy. It was impossible to raise the issue of immigration without being labelled racist, or of leaving the EU without being insulted as a fanatic. Mainstream arguments to shrink the size of the state, or even to challenge its growth, were regarded as a sign of madness or inhumanity — hence Michael Howard’s decision to sack Howard Flight for advocating just that during the 2005 election campaign. The NHS and Britain’s collapsing education system were beyond criticism. Any failure to conform was policed by the media, and the BBC in particular.

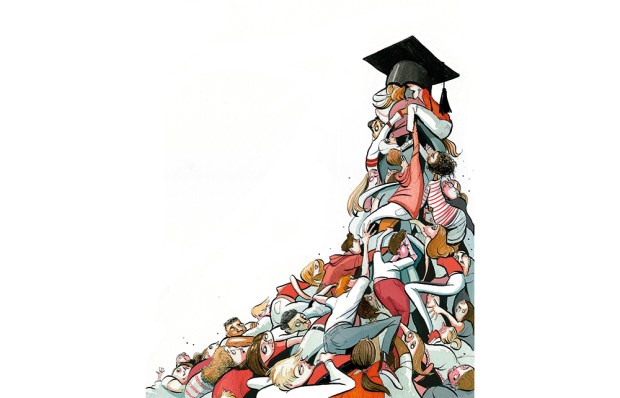

Meanwhile, the three main political parties had been captured by the modernisers, an elite group which defied political boundaries and was contemptuous of party rank and file. As I demonstrated in The Triumph of the Political Class (2007), politicians suddenly emerged as a separate interest group. The senior cadres of the New Labour, Conservative and Lib Dem parties had far more in common with each other than ordinary voters. General elections were taken out of the hands of (unpaid) party activists and placed in the hands of a new class of political expert. Ed Miliband’s expensive American strategist, David Axelrod, who flew into London on a fleeting visit to the shadow cabinet last week, is an example.

In this new world, the vast majority of voters ceased to count. The new political class immediately wrote off all voters in safe seats — from unemployed ship-workers in Glasgow to retired lieutenant colonels in Tunbridge Wells. Their views could be disregarded because in electoral terms they were of no account. This callous attitude brought into existence a system of pocket boroughs in parts of Scotland, driving traditional Labour voters into the hands of the SNP and (as can now be seen clearly with hindsight) jeopardising the union. The only voters that political modernisers cared about were those in Britain’s approximately 100 marginal seats — and even the majority of those were considered of no significance. During the 2005 general election I went to see the co-chairman of the Conservatives, Maurice Saatchi, who boasted that barely 100,000 swing voters in the marginal seats mattered to him. Saatchi reassured me that the Conservative party had bought a large American computer that would (with the help of focus groups) single out these voters and tell them what they needed in order to make them vote Conservative.

The majority of national journalists, for the most part well-paid Londoners, were part of this conspiracy against the British public. They were often personally connected with the new elite, with whom they shared a snobbery about the concerns of ordinary voters.

Immigration is an interesting case study. For affluent political correspondents, it made domestic help cheaper, enabling them to pay for the nannies, au pairs, cleaning ladies, gardeners and tradesmen who make middle-class life comfortable.

These journalists were often provided with private health schemes, and were therefore immune from the pressure on NHS hospitals from immigration. They tended to send their children to private schools. This meant they rarely faced the problems of poorer parents, whose children find themselves in schools where scores of different languages were spoken in the playground. Meanwhile the corporate bosses who funded all the main political parties (and owned the big media groups) tended to love immigration because it meant cheaper labour and higher profits.

Great tracts of urban Britain have been utterly changed by immigration in the course of barely a generation. The people who originally lived in these areas were never consulted and felt that the communities they lived in had been wilfully destroyed. Nobody would speak up for them: not the Conservatives, not Labour, not the Lib Dems. They were literally left without a voice.

To sum up, the most powerful and influential figures in British public life entered into a conspiracy to ignore and to denigrate millions of British voters. Many of these people were Labour supporters. Ten years ago, when Tony Blair was in his pomp, some of these voters were driven into the arms of the racist British National Party and its grotesque leader Nick Griffin. One of Britain’s unacknowledged debts to Nigel Farage is the failure of Griffin’s racist project. Disenfranchised Labour voters tend to drift to the SNP in Scotland and Ukip in England.

Here is the second debt that Britain owes to Nigel Farage. Until his arrival on the scene, political debate was in the hands of calculating machines like George Osborne and Peter Mandelson. For them politics is neither more nor less than a cynical game, the possession of the elite. Their real objective was the abolition of politics itself, at any rate as it had been understood during the age of mass democracy.

Nigel Farage and Ukip have brilliantly challenged the arrogance of this political class. Look at the way that David Cameron, at first contemptuously hostile, has been forced to throw his weight behind the referendum. Without Nigel Farage, this year’s Euro elections would have been meaningless and a degradation of democracy. Thanks to Ukip, they have served a visceral political purpose and changed the nature of our national debate.

Rather than stay silent about great issues of the day, the main parties have been forced into the open. The last few weeks have seen the most thoroughgoing debate about immigration Britain has ever had, with Ukip forced to defend its position. It has lost many of the arguments — but at last they are being heard and tested.

For ten years, academic theorists and political experts have been wringing their hands about voter apathy. The Hansard Society would annually come up with a new proposal to remedy declining turnout at general elections. Baroness Helena Kennedy’s Power Inquiry conveyed its earnest bafflement about the readiness of the British people to join charities like Oxfam while turning their backs on our national politics.

In reality, it was the British politicians who turned their back on the electorate, not the other way around. The voters were much less apathetic than the national politicians assumed and (horrifying for the Helena Kennedys of this world) Ukip is the party that has proved it.

Nigel Farage has made plenty of mistakes in his campaign, and his attack on Romanians in last week’s LBC interview was lamentable. But he has shown remarkable stamina and, most of all, he has given British democracy back to the people it belongs to — the voters.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Peter Oborne is chief political commentator of the Daily Telegraph and an associate editor of The Spectator.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in