The Bauhaus was a sort of university of design, whose progressive ideas eventually fell foul of the Nazis. But as the exhibition Bauhaus: Art as Life is keen to impress, it was also a lifestyle, a modernist utopia, where staff and students were encouraged to mix freely, which they did with gusto. This, just as much as its reputation as a nerve centre for a new aesthetic, made it a magnet for the central European avant-garde. Among its teachers were some of the greatest artists and designers of the 20th century: Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee taught art; Marcel Breuer was responsible for furniture; Laszlo Moholy-Nagy for product design; Oskar Schlemmer for performance; and Walter Gropius, the school’s founder, lectured on architecture.

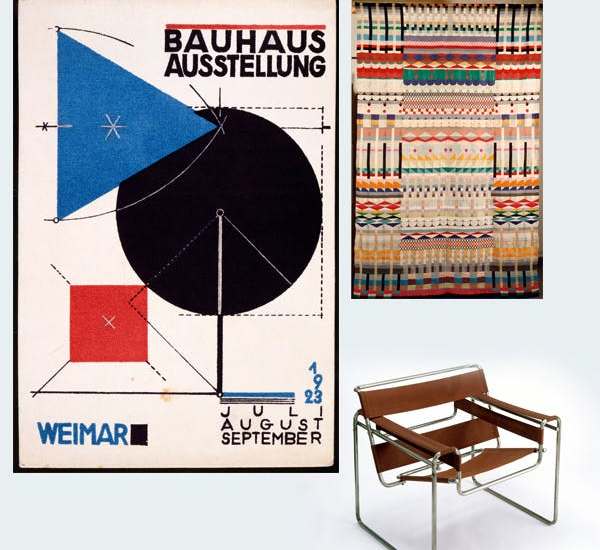

Rather improbably, the first Bauhaus exhibition, in 1968, was held at the Royal Academy whose mission — to raise the professional status of the artist — is at odds with Bauhaus ideology, which thought that art was bourgeois: ‘It is harder to design a first-rate chair than paint a second-rate painting — and much more useful,’ was one of the school’s guiding principles.

The Barbican arts centre is a more appropriate setting and a wealth of new material helps tell a more rounded story, not simply about the personalities but also about its folksy, Teutonic roots and hippyish early years at Weimar under the direction of the Swiss-born painter Johannes Itten.

After Itten resigned and Gropius hired Moholy-Nagy, the Bauhaus moved to Dessau in 1926 and reinvented itself, determined to solve practical questions like mass housing using modern materials such as steel, glass and concrete. A large model of the new school designed by Gropius shows an austere but beautifully co-ordinated building and it’s here that the Bauhaus flourished.

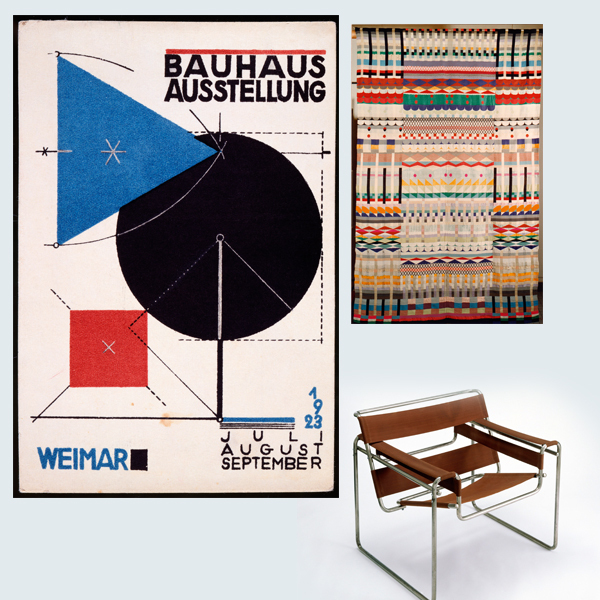

There are 400 exhibits, from teapots to typefaces and painting to packaging, laid out according to the workshops that every student had to participate in. A revelation is the carpets and wall hangings by Anni Albers and Gunta Stölzl (despite Gropius’s championing of sexual equality few women made it out of the weaving workshop) because they introduce colour into an architecture that was gradually being reduced to white and grey.

More familiar is the furniture; Marcel Breuer’s Wassily Chair, inspired by the tubular steel handlebars of an Adler bicycle, can be bought in the Barbican shop for £1,114, a sharp reminder that, despite its huge influence on 20th-century design, the real thing was not within most people’s reach. But it wasn’t just cost; it was also taste. Many of the designs are pretty odd. A ‘standardised teapot’ to which a handle, spout and lid could be added is a case in point. And Bauhaus staff aside, people weren’t prepared to sit on chairs that were uncomfortable, or live in houses that had white walls, a flat roof and strip windows.

While there is plenty to enjoy, there’s also something missing and that’s the anarchy. Instead of fizzing with mischief and rebellion, the photographs and memorabilia of the parties — one involved dressing up in tin foil and frying pans and sliding down a chute into a room decorated with silver balls — the Bauhaus jazz band, puppet shows and kite festivals all seem like a gloomy portent of what lay ahead.

As for the Nazis, Bauhaus ideas were the antithesis to their own; cosmopolitan, modernist and therefore Bolshevik, it was also, inevitably, Jewish. The influence of politics on the course of architecture is a fascinating subject but beyond the scope of this show, which stops abruptly in April 1933. The typewritten letter by the school’s last director, Mies van der Rohe, announcing the closure of the school, now housed in a disused telephone factory in Berlin, makes it seem like the end. In a way it was, but in another way it was a new beginning because it marked the great exodus of modern architects from Germany.

After a brief stay in England, Gropius along with Mies emigrated to America, where they quickly found prestigious academic posts. Other Bauhaus masters followed them. Gropius became head of architecture at Harvard; Moholy-Nagy at the New Bauhaus in Chicago; Mies was installed as dean of architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology.

In 1938 the Museum of Modern Art held the first Bauhaus exhibition outside Germany and Bauhaus (a word that translates as ‘building house’) had become shorthand for a modern, functional design that was quickly absorbed around the world. The Nazis hadn’t stamped out the Bauhaus, they’d liberated it.

Amanda Baillieu is editor-in-chief of Building Design.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in