Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) spending review rounds always work like this: officials choose three figures of increasing severity and ask those they fund to model what would happen should their funding be cut by the corresponding amounts. The organisations duly devote considerable resources to trying to work out what they could cut or stop doing entirely, worrying staff and donors and driving speculation in the press. Then the culture secretary of the day proudly announces that he or she has fought culture’s corner and we all now only have to cut by the lower figure. Cue grateful thanks in public, and private pain as the agreed changes are made.

This is no doubt the same across Whitehall, but in culture and the arts it seems a particularly merry dance. Last week, the Culture Secretary Maria Miller secured cuts of ‘only’ 7 per cent to the overall DCMS budget in 2015/16, and ‘only’ 5 per cent to national museums and galleries. This perhaps seems reasonable — low even, when compared with cuts of almost 10 per cent to the Work and Pensions and Transport budgets. But the 5 per cent cut comes on top of years of slicing: in real terms, grants to institutions such as the British Museum, Science Museum and National Gallery have already been cut by a quarter since 2010. In fact, in real terms, funding is back to the level it was at before government boosted museum grant-in-aid to enable free admission in 2001.

But while the elite group of DCMS-funded national museums will survive, only bruised by the latest round, most of the smaller, local authority museums will be more severely wounded, and some may not survive at all in the long run. For the real threat to UK culture comes in the announcement of the local government budget cut of 10 per cent, on top of more than 25 per cent cuts since 2010. This, coupled with the 5 per cent cut to the Arts Council budget (on top of the more than 30 per cent it has already suffered), is a double blow, and we’ll undoubtedly see further job losses, shorter opening hours, mergers and possible closures. Discretionary arts and heritage services are often seen as a soft touch by local authorities, and a number of councils, including Moray in Aberdeenshire and Westminster, have already confirmed 100 per cent cuts to their arts budget. Some, like Northampton and Croydon, are looking to sell up parts of their art collections to claw back funds.

It doesn’t have to be like this. Nine of the ten finalists for this year’s Art Fund Prize for Museum of the Year were funded by local authorities and/or Arts Council England, and all are beacons of what can be achieved with local support and political will. The superb William Morris Gallery in north-east London was crowned the winner last month, a museum in dire straits just five years ago but one since transformed with local investment, including substantial funds from Walthamstow Council to match a Lottery grant. My fellow judge Sarah Crompton described it recently in the Telegraph as ‘exemplary …a pattern, despite its relatively small size, for what a museum can and should be’. Might other councils take their lead from authorities such as Walthamstow, Canterbury or Wakefield, and grasp the social, educational and economic importance of culture and the returns it can bring?

Special pleading in tough times is usually inadvisable, and museums and arts bodies have, for the most part, wisely refrained from declining to take their fair share of austerity. But while the cuts save comparatively small sums for central government, they do create a much wider loss to the broader economy and society. Museums drive visitors and tourism: 40 per cent of people who come to the UK cite culture as the most important reason for visiting. Eight of our top ten visitor attractions are museums and galleries, and three of the top five art museums in the world are in the UK. They do create jobs and boost the economy: for every £1 invested in the arts, we get £4 back. In London alone, the arts and culture sector generates 400,000 jobs and returns £18 billion to the economy. The fact is, across the UK, public investment in the arts pays. If anyone thinks a 5 per cent cut might only mean one fewer exhibition a few years down the line, think again.

Museums and arts organisations have been encouraged to raise funds themselves, particularly through corporate support and philanthropy, and many have done so successfully, from Tate (on a spectacular scale) to Tyne and Wear (where it’s a bit harder). But sustained public funding is needed in the first place: it provides the bedrock on which philanthropy and other funds can build. The Natural History Museum successfully raised £78 million to open the Darwin Centre in 2009, but a financial commitment from DCMS sowed the first seed. And for all the warm words, we know that attracting philanthropic support outside London is still very difficult: Yorkshire millionaires keen to hand over cash to the Ferens Art Gallery or Doncaster Museum are unfortunately few and far between.

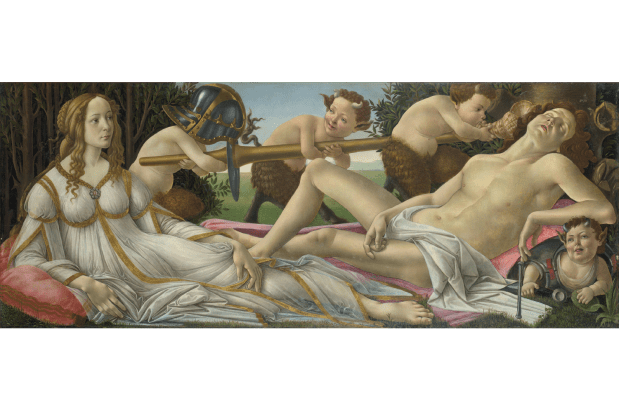

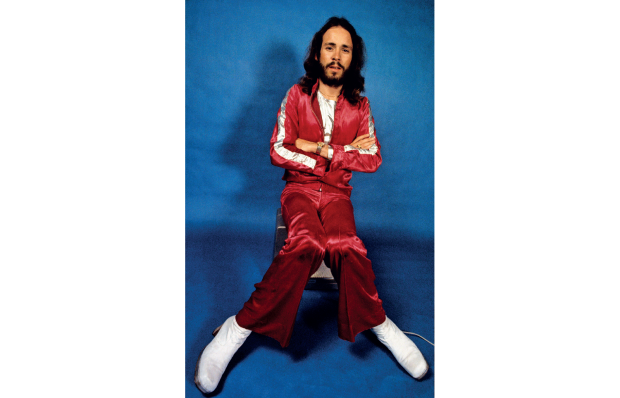

We have seen 20 years of investment in our museum and gallery buildings, largely through the Heritage Lottery Fund and the public purse. We routinely used to hear talk of roofs about to cave in and damage to the collection, or burst pipes, but while things aren’t perfect, we rarely hear this today. Our museum buildings have never been in better shape. Meanwhile public interest in culture is riding high: the Art Fund’s recent announcement that it now has more than 100,000 museum-going, National Art Pass-waving members is testament to that. More than half of the UK population visited a museum or gallery last year, and exhibitions like Bowie at the V&A or Lowry at Tate Britain attract an ever broader audience. The Artist Rooms collection of more than 700 modern and contemporary works, including those by Andy Warhol and Joseph Beuys, perpetually touring galleries and spaces across the country, has now been seen by several million people, from Falkirk to Bexhill. Loudly and clearly the public is saying that it loves our museums and their collections. And we should all be proud of their perceived prowess on the international stage.

How long before the reality of strength fades to illusion? Further cuts will inevitably have an impact on frontline services. With the high fixed costs of collections care, programming and exhibitions will be disproportionately affected. Jobs will go first. Yet, across the past two decades, driven by public and Lottery investment, we have created, built, repaired and polished extraordinary arts institutions across the country, and have eager audiences of all ages, from all corners, clamouring to get in. If we don’t continue to invest in the people and contents — in the curators and conservators, the collections and exhibitions — the payback will never come. Then, we may ask, what was the point of it all?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in