My compatriots have not always been kind in their assessment of your country. ‘When I think of Melbourne, I vomit!’ wrote Robert Louis Stevenson, rather cruelly. ‘Everyone complains of the high rents and difficulty in procuring a house,’ observed Charles Darwin, in a statement that foreshadowed a thousand eastern suburbs dinner party conversations. ‘This country is American,’ wrote Rudyard Kipling, bemoaning Australia’s derivative tendencies, ‘but remember it is second-hand American.’ Agatha Christie thought Australians relied too heavily on the mother country, and were ‘a bit too hospitable for English ideas’, another salutary thought at a time when the Australian press has happily stepped into the frenzy surrounding the birth of the royal baby.

Not that I would put myself for a moment in remotely the same company, I have never found it difficult to write admiringly about a country that has been my home now for six years. Though my reason for coming here was because I had fallen in love with an Australian, it was not long before I had fallen for Australia, as well.

Damning though I have been about the recent quality of Canberra politics — much to the editor’s ongoing annoyance — I have written more kind words than snarky. For a start, Australia is the great ‘lifestyle superpower of the world’. The cultural cringe, the national contagion diagnosed by A.A. Phillips 60 years ago, has been replaced by Australia’s cultural creep. From Peter Carey to Sidney Nolan, from Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu to the brilliant Australian Chamber Orchestra, from Cate Blanchett to Meow Meow, there is a far greater global appreciation of this country’s artistic exports now than when

I arrived.

Back then, it seemed faintly ludicrous to me that many locally produced maps placed this vast continent in the position that Brits would ordinarily expect to see the Greenwich Meridian — Julia Gillard used to have one on the wall in her suite of offices. Now, though, it seems fitting that young Aussies are taught to believe their country occupies a central place in the world. In the national conversation, a sense of proximity has replaced the notion of distance.

If only the national vocabulary would catch up. The ‘land Down Under’ is a British construct with London the geographic point of reference. So, too, the Antipodes. The implication is that irrelevance is the corollary of isolation. As for the idea that this is an immature country still in the throes of adolescence? Please. Nor did the Sydney Olympics somehow mark its ‘coming of age’. National adulthood had been reached decades before that lone horseman came hurtling into the Olympic stadium

at Homebush.

Nor, of course, is this a Lucky Country, blessed though it is with golden sands and iron-filled mines. Donald Horne’s may be the finest book ever written about Australia, but its widely misunderstood title remains a bar to understanding. I have watched it become the ‘Consequential Country’, a phrase nowhere near as ringing, but one that at least addresses Australia’s unprecedented levels of economic, commercial, cultural and diplomatic clout.

In measuring Australian influence, I used to refer the New York Times index, a gauge used by Bill Bryson before he began writing Down Under. For him it highlighted this country’s irrelevance, because while Albania got 150 mentions in the paper in 1997, when he set out to write the book, little old Australia merited a measly 20. Now, though, the Grey Lady’s coverage is so thorough that its resident correspondent even reported on the creation of Clive Palmer’s new political party. Besides, these days we could just as easily talk about the New Yorker index. In the past six months alone, the magazine has run lengthy essays on Gina Rinehart, the object of global fascination, and MONA in Tasmania, underscoring the point about Australia’s commercial and cultural clout.

Here, I am in danger of falling into the same trap as Australian Twitter, which seems to go into paroxysms of ecstasy — or, perhaps, spasms of lingering cringe — whenever the New Yorker sees fit to mention this country. But I struggle to think of a peaceful country with an equivalent population that receives so much global attention. That is one of the reasons why the present parochialism of Canberra politics, with its ‘Small Australia’ mindset, is so dispiriting. Certainly, news editors, much like diplomats and cultural brokers, no longer require peripheral vision to

make out Australia.

So I very much buy the idea of ‘The Australian Moment’, George Megalogenis’s pithy term for this phase of national success. That said, I fear it might end up being inadvertently precise. The moment could indeed be fleeting. The big, imaginative thinking of Bob Hawke, Paul Keating and John Howard that helped create it is largely absent from the political debate. ‘Australian Moment’ thinking requires ‘Big Australia’ thinking. The present phase of miserable politics arguably started when both Julia Gillard and Tony Abbott endorsed a ‘Small Australia’ immigration policy at the beginning of the 2010 campaign.

There are problems aplenty. Australia’s infrastructure is in urgent need of renewal, as any new arrival who has stopped off en route in Bangkok, Thailand or Hong Kong will attest. Melbourne and Sydney airports would benefit from some blue-sky thinking. In a country obsessed with global benchmarking, it is surprising how far its transport infrastructure now lags behind. And is it also not depressing that the most talked-about structure in Australia right now, James Packer’s Barangaroo tower overlooking Sydney Harbour, will eventually house a casino?

Just as Australia could do with getting an airport into the global top 20 — Brisbane currently stands at 21 — it could do with a university in the top flight. Though it can boast the third-largest number of universities in the top 100 of any nation, it has none in the top 25. As far as public investment is concerned, Australia ranks 25th out of 29 countries in the OECD league, which makes it all the more surprising that the government responded to Gonski by proposing a cut in funding. A combination of history and massive endowments make powerhouses like Cambridge and Harvard impossible to overtake, but Australia accepts too easily that the apogee of academic achievement is a Rhodes scholarship to Oxford.

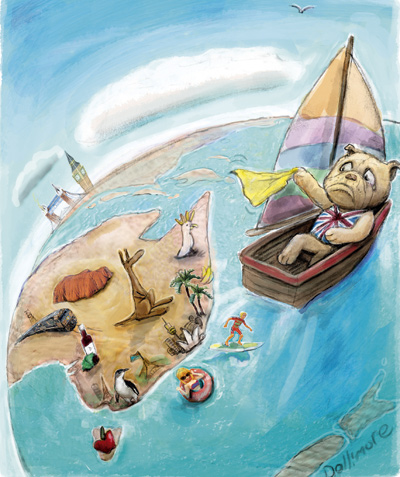

As with America, a dated constitution is no longer fit for purpose. Its renovation should begin by recognising Indigenous Australians at the earliest opportunity. But there also needs to be a re-evaluation of the balance of power between the Federal government and the states. Having met so many ‘can do’ Aussies before arriving here — the ranks of BBC cameramen would be badly depleted without them — I had not reckoned on the pervasiveness of ‘can’t do’ constitutional inertia. The ongoing attachment to the Australian monarchy, witnessed during the Royal Wedding when pub plasma screens were switched from the footy to the nuptials, has also come as a surprise. Arriving in Australia six years ago, I expected to cover another Republican push, and assumed, wrongly, it would be successful. I had not realised that Australians are more accepting of British elites than their own.

Even without the inauguration of Australia’s first president, this has been an extraordinary period in which to report Australia for the BBC. From my front-row seat on Aussie history, I watched the end of John Howard, the fall of Kevin Rudd, the defenestration of Malcolm Turnbull and the rise of Tony Abbott, a story that few would have predicted six years ago. I have covered the worst bushfires to hit this country, Victoria’s Black Saturday, and also some of its most widespread flooding. I have heard a black American President announce an Asia pivot on Australian soil, and seen the Australian dollar, the once-mocked ‘Pacific Peso’, reach parity with the greenback. Talks between the British and Australian government’s — the awkwardly named AUSMIN dialogue — are now an annual event, signifying a new sense of diplomatic parity, too.

On visits home, I have also witnessed my own country become noticeably more Australian. You see it in the tie-less informality of a new workplace dress code, the prevalence of the word ‘mate’, the new-found professionalism of our national sports teams, the embrace of the backyard barbeque, the availability of the flat white and the generation of middle-class Londoners being raised by twentysomething Aussie nannies. Then there are the successive generations of British journalists who have tried, and failed, to impersonate Clive James.

Some major stories have not lent themselves easily to headlines, foremost among them the ever-increasing influence of China. In April 2011, I did not file a dispatch back to London reporting that Chinese immigrants outnumbered British arrivals for the first time in the history of modern Australia. In the coming decades, however, it may well end up changing the character of this country more profoundly than any of the stories that have made into BBC bulletins.

There have been negative stories, too. There is no denying that the harshness of offshore processing incurs reputational damage abroad. So, too, does the brutality of Canberra politics, whether from the capital’s coup culture or the childishness of Question Time. Both I will be glad to leave behind.

Yet there are countless other things I will miss, from the beaches to the bush, from the irreverent humour to the lack of pretention, from the dawn cry of the kookaburra to the sound of our resident possum dancing nightly on our roof. The ‘bingeing Pom’ in me will find it hard to live without such a diverse menu of exquisite food. And few countries take such care over their cappuccinos, lattes and flat whites, a point driven home to me during the Queensland floods, when I witnessed a barista rescuing his beloved espresso machine from a flooded Brisbane café, then carry it to safety as if cradling a new-born child.

Happy though I will be to experience Christmas in winter and autumn in October, I will miss the southern summer and also the five words that usher it in: ‘Good morning from the Gabba,’ uttered by my favourite Australian commentator, the incomparable Jim Maxwell.

Melbourne never did make me vomit. Quite the opposite. Nowadays, it has become one of the world’s great over-achieving cities. The same could never be said of Sydney, a breathtaking though underperforming city. But at least it has awoken finally from its post-Olympics slumber. If only the money could be found to bury the Cahill Expressway underground, to build a permanent, Bilbao-style art gallery on Cockatoo Island, and for the Opera House to finally realise Jørn Utzon’s spectacular original vision.

Your great cultural cathedral, the Sagrada Familia of the south, has exerted an almost mesmerising hold on me ever since I first saw it, distantly, from the traffic lights at the top of Bondi Road. Over the years, I have also come to view the building as allegorical, for it encapsulates so many of Australia’s internal contradictions. It’s a symbol of post-war ambition and internationalism, but also, because of Utzon’s forced resignation and his replacement with a local architect, of short-termism and parochialism. New immigrants from southern Europe provided much of the manpower for its construction. Paul Robeson, the black American opera star, even performed a concert surrounded by its scaffolding and cranes, a musical foreshadowing of the end of the White Australia policy. It was opened by the Queen, but in a ceremony that included Indigenous ritual. It has been a focal point of national celebration and also of protest. Its opening programming included Sir Charles Mackerras conducting the prelude to Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and Rolf Harris singing ‘Tie Me Kangaroo Down, Sport.’ Why, the project was even financed through gambling. But the main reason that the Opera House works so well as a national symbol is that it is glorious though incomplete.

‘Farewell Australia,’ wrote Charles Darwin, as he left these shores, ‘you are a rising infant and doubtless some day will reign a great princess in the South.’ That day arrived long ago. Besides, Australia no longer yearns for foreigners to affirm its national success.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Nick Bryant has just taken up his post as the BBC’s New York correspondent.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in